Journalist Alfredo Corchado and I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on April 14, 2005.

He calls himself a humble bean farmer, but Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera is described by U.S. drug agents and intelligence documents as one of the most powerful and cunning drug lords Mexico has ever known.

Mr. Guzmán, a 50-year-old prison escapee, is at the center of a violent turf war that, by Mexico’s count, has left more than 250 people dead across the country.

In the latest clash on Sunday, as many as 30 men wearing ski masks opened fire on a police convoy near a Nuevo Laredo shopping center, Mexican police said. Six officers, including the state police commander, and two passers-by were injured in a ferocious hail of gunfire that left behind nearly 500 bullet casings, an unused bazooka and the remains of two 40 mm grenades.

Federal police in Mexico say they don’t know who was responsible but are convinced that catching Mr. Guzmán would help end the violence that’s been plaguing the nation’s border states. In recent weeks, they have stepped up their search for the drug lord, raiding his family’s homes and ranches in Jalisco and other states.

American agents are assisting with intelligence information, and the State Department has put up a $5 million reward for information leading to the arrest of El Chapo, or the Short One, as he is known.

“He’s going to get caught sooner or later,” said Misha Piastro, a special agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration in San Diego, where Mr. Guzmán is wanted on drug conspiracy charges. “We have a great working relationship with Mexican authorities. Hopefully Chapo will be the next notch on our collective belt.”

Even some of the Mexican government’s harshest critics are impressed with the hunt.

“There is a sincere effort by Mexican authorities to get the guy,” said a former veteran DEA agent. “But he has been elusive. He’s an Osama-like figure, and he has a lot of Taliban protecting him.”

Living legend

Mr. Guzmán is a legendary figure in the Mexican underworld.

In the 1980s, the DEA said, he was the first trafficker to export cocaine in fire extinguishers. Later he developed alternative drug routes through Central America to thwart Mexican radar systems. He also pioneered the use of sophisticated, carefully engineered tunnels to shuttle drugs under the border.

El Chapo runs his smuggling business much like a multinational corporation but with a deadly difference, said a federal drug agent who has tracked Mr. Guzmán.

“When Donald Trump calls you into the boardroom, you might lose your job. But when Chapo Guzmán calls you in, you might lose your life,” the agent said. “His business is crime.”

And over the years, El Chapo has shown an uncanny ability to focus on his business even when he’s on the run or in extreme peril, according to a 116-page U.S. intelligence document obtained by The Dallas Morning News.

Take what happened in 1993. Tijuana’s Arellano-Felix drug gang had sent hit men to the Guadalajara airport to assassinate El Chapo, the intelligence report said, but they mistakenly shot a Catholic cardinal, triggering a massive hunt for both the hit men and their intended target.

Take what happened in 1993. Tijuana’s Arellano-Felix drug gang had sent hit men to the Guadalajara airport to assassinate El Chapo, the intelligence report said, but they mistakenly shot a Catholic cardinal, triggering a massive hunt for both the hit men and their intended target.

“Chillingly, Guzmán Loera continued his illicit activity in the hours that followed,” the intelligence report said. Even as “virtually all elements of Mexican drug authorities” were trailing him, Mr. Guzmán “was immersed in a transaction” for 5.85 tons of cocaine hidden in a warehouse in El Salvador.

The El Paso Intelligence Center, the largest counternarcotics agency of its kind, produced the June 1994 report on El Chapo and his organization. Although portions of it are outdated, it provides rare insight into one of the most important figures in Mexican drug trafficking today.

According to the document:

Mr. Guzmán was born on Christmas Day 1954 in Mexico’s so-called Golden Triangle, the cradle of Mexican drug smuggling where the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Sinaloa meet.

Relatives may have helped El Chapo get his start. His uncle, Carmelo Áviles-Labra, was an infamous trafficker who was murdered in Culiacán, Sinaloa, in May 1994.

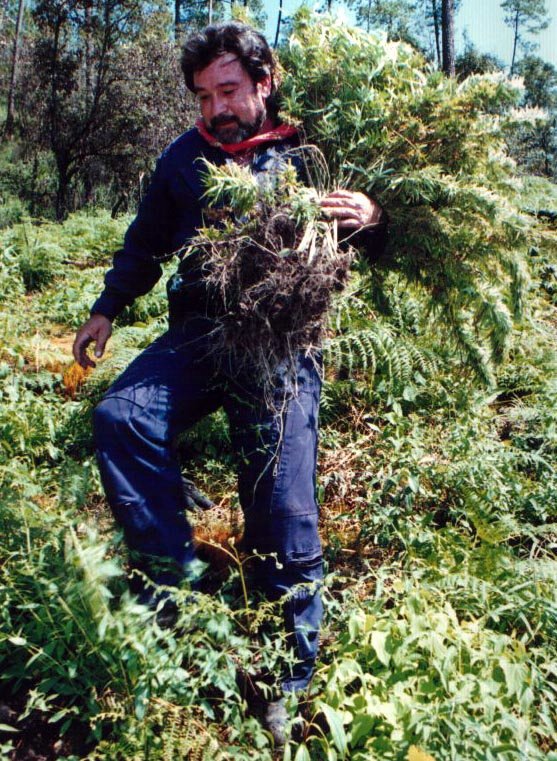

Young Mr. Guzmán attracted law enforcement’s attention in the early 1980s. He was “an overseer of illicit crops in the fertile regions of the states of Sinaloa and Durango,” the intelligence report said.

Among his bosses was Juan José Esparragosa Móreno, nicknamed El Azúl, or Blue. He was on the verge of being jailed in 1986 and needed someone he could trust. That’s probably when he decided to promote El Chapo to logistics chief for their Sinaloa organization, the report said.

Mr. Guzmán went to work coordinating the arrival of aircraft from Colombia. Medellín cartel traffickers were soon calling him El Rápido – the Fast One.

“He was the first Mexican trafficker to pompously guarantee the delivery of contraband in the United States within 48 hours of receipt,” the report said.

Business was good. From 1987 to 1989, Mr. Guzmán’s trafficking group smuggled 20 to 24 tons of cocaine every month, authorities said.

“In most cases, Guzmán Loera handled no less than 10 to 12 aircraft at one time,” the report said. “Since each operation might cost him approximately $10 million, maximum involvement of aircraft was requested to make it cost-effective.”

Back then, Mr. Guzmán boasted to the Colombians that he paid police officers and others $5 million per month to operate. He called that his “security bill.”

El Chapo also said he was close to the Mexican attorney general, the report said, and other drug traffickers reportedly sought him out so he could “open the door to corrupt officials.”

In April 1993, Mr. Guzmán allegedly gave $1 million and five Dodge Ram Charger pickups to a Jalisco police commander so he’d allow two drug-laden planes to land, the report said.

El Chapo shelled out cash for valued employees, too. In February 1991, he and another trafficker allegedly spent $5 million to secure the “escape” of two preferred pilots who were in a maximum-security prison, the report said.

Connections

Mr. Guzmán wanted other traffickers to know that he had government connections, U.S. agents said. On one occasion, when flying his private Learjet to Colombia to attend a party hosted by a known kingpin, he made sure that Mexican police officials filled his plane.

Before long, however, his long-running rivalry with the Arellano-Felix gang began interfering with business.

In November 1992, he reportedly sent 40 gunmen into a Puerto Vallarta disco where the Arellano-Felix brothers were partying. A shootout erupted and nine people were killed.

The Arellanos retaliated by sending assassins to murder Mr. Guzmán at the Guadalajara airport on May 24, 1993. The accidental killing of Cardinal Juan Jesús Posada Ocampo triggered a massive outcry, and El Chapo took refuge in Guatemala.

Police captured him on June 9, 1993, and jailed him in Mexico.

U.S. agents say he continued to do business from prison. Then on Jan. 19, 2001, Mexican authorities said, he hid in a laundry cart as accomplices whisked him from a Guadalajara prison, past well-paid guards and a series of electromagnetic doors.

Mexican officials have been trying to capture him ever since.

After another embarrassment, when an aide to President Vicente Fox was jailed in February for allegedly selling sensitive information to a Guzmán operative, the search intensified.

Mysterious wanted posters for the trafficker began appearing on buildings and utility poles in Monterrey and other northern cities.

“Denounce them! For Mexico, for our children!” read the posters, urging passers-by to call a tip line and offering a separate $5 million reward.

Mexico City’s Reforma newspaper traced the tip line and said it appeared to be a military operation. But as yet, no one in the government has accepted responsibility for the hotline or the reward.

Presidential aide Nahum Acosta, meanwhile, was freed Saturday after a judge said prosecutors failed to prove their case.