I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on May 18, 2003.

Cuban spies are in a bragging mood these days.

They say American pro-democracy groups have unwittingly pumped tens of thousands of dollars into Fidel Castro’s intelligence agencies over the past decade.

U.S. officials put so much trust in one Cuban spy posing as a dissident that they allowed him to organize an ethics workshop at the home of the top American diplomat, Cuban agents say. And, they say, the Americans supplied other spies with laptop computers, televisions, digital cameras and tape recorders, believing that these individuals belonged to the political opposition.

“It was a game,” said Pedro Luis Veliz, a spy who falsely claimed he led an 800-member opposition group in order to squeeze more money out of private American organizations, many of them financed in part by the U.S. government.

U.S. officials concede there have been setbacks in their efforts to advance democracy, but they deny financing Cuban dissidents inside Cuba.

U.S. officials concede there have been setbacks in their efforts to advance democracy, but they deny financing Cuban dissidents inside Cuba.

Cuban officials “can say whatever the hell they want,” said a U.S. official who requested anonymity. “They say we paid them. We say we didn’t. There’s no smoking gun.”

The Cuban accusation is “defamatory and fallacious,” said Kevin Whitaker, chief of the State Department’s Office of Cuban Affairs.

To some critics, the American efforts are not only ineffective, they hurt dissidents more than they help.

“The U.S. error is to try to buy change,” said Marta Rojas, a Cuban author who supports Mr. Castro. “They think that by giving people VCRs and money that things will change.”

“All this prodding and provoking … the only thing it accomplishes is to get the kind of crackdowns that we’ve seen,” said Wayne Smith, a former chief U.S. diplomat in Havana.

The crackdown he’s talking about occurred in March, when Cuban authorities arrested nearly 100 dissidents. Seventy-five were sentenced to up to 28 years in prison after widely condemned summary trials, and 60 are now reported in solitary confinement.

The few dissident leaders who escaped arrest are trying to rebuild the shattered opposition movement.

“Unfortunately, we’re at the mercy of the Cuban government,” said Vladimir Roca, a veteran dissident in Havana.

U.S. officials and private groups, are re-evaluating their strategy. They say they’re determined not to back down.

“The government’s crackdown is clearly a setback. However, the inevitability of change in Cuba is just as clear,” James Cason, chief of the U.S. mission in Havana, told an audience in Miami on April 7. “Change will come to Cuba.”

U.S. officials add that Cuba’s repressive government – and not the United States – is to blame for the March crackdown.

Mr. Castro’s fear led to the arrests, Mr. Whitaker said.

Mr. Castro denies that.

“Our neighbors to the north can tell lies … but they can’t win a single political battle because they know nothing about politics,” he said last month.

The U.S. Agency for International Development, or AID, sends books, videos and other materials to Cuba through private, U.S.-based organizations.

A March report on the agency’s Cuba program shows that $21.8 million has been allocated or spent since 1996. That includes $11.6 million to “build solidarity” with human rights activists; $2.3 million “to give voice to Cuba’s independent journalists;” $1.6 million to help develop non-governmental groups; $592,575 to help defend workers’ rights; $2.7 million for “direct outreach” to Cubans; $2.6 million for transition studies and planning; and $335,000 to conduct polls and to evaluate the program’s effectiveness.

Most of the money stays in the United States, funding pro-democracy Web sites, research, training programs and other projects at universities, anti-Castro organizations and other groups.

A lesser amount – U.S. officials decline to say how much – is spent on food, medicine, books and humanitarian assistance that is sent to Cuba.

The U.S. government has sought for years to bolster the political opposition in Cuba.

A key U.S. goal is to “increase the flow of accurate information on democracy, human rights and free enterprise” in Cuba and elsewhere, said Adolfo Franco, a Cuban-American who is AID’s assistant administrator for Latin America and the Caribbean.

“Since 1996, U.S. AID grantees sent over one million books, newsletters, videos and other informational materials to independent non-governmental organizations and individuals in Cuba,” he said. “No U.S. AID grantee is authorized to use grant funds to provide cash assistance to any individual or group in Cuba.”

Audits required

But if the grantees have money from other sources, he said, they are free to send it to Cuba as long as they don’t break U.S. law.

He added that AID requires independent annual audits of groups that receive more than $300,000 per year. The audits have not uncovered “any material weaknesses” in the program so far, he said. And some of the assistance is set aside for members of Cuba’s political opposition, the families of political prisoners and “other victims of repression.”

Cuban agents say that since some of the so-called “dissidents” are actually spies, some funds end up helping to finance Cuba’s state security operations.

The socialist government benefits – and so do the spies, said Odilia Collazo, alias Agent “Tania.”

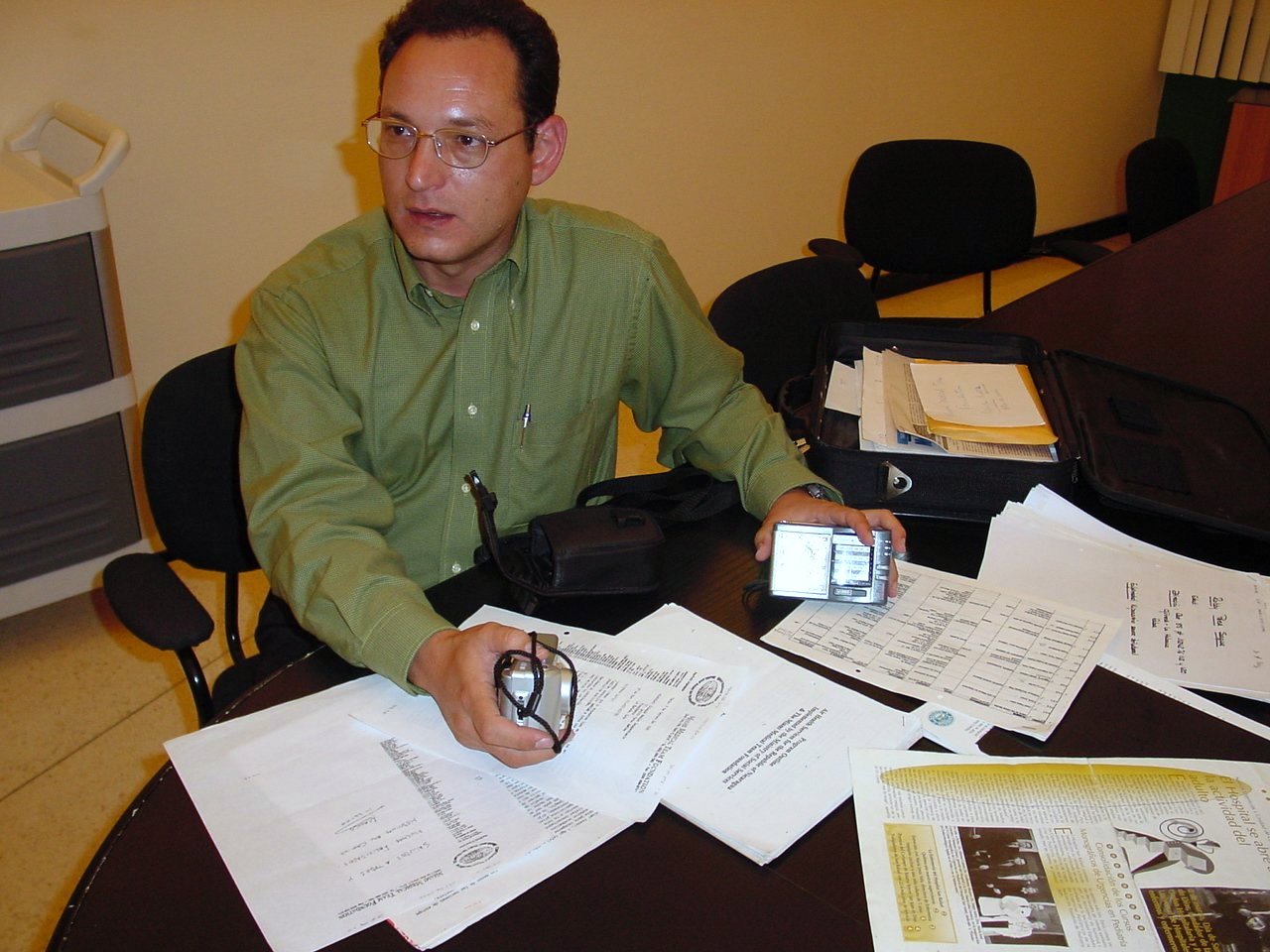

She said she was destitute when she began spying on dissident groups in 1990. Now she says she has a car, a television, VCR, computer and digital camera – all thanks to American pro-democracy groups.

U.S. officials knew her as the leader of a dissident group, the Pro-Human Rights Party of Cuba. She said AID-funded groups gave her $450 per month and sometimes more. In return, she investigated human rights violations and sent reports to the United Nations and other organizations.

Most of her reports lashed out at the Cuban government. But Ms. Collazo wrote them anyway.

Most of her reports lashed out at the Cuban government. But Ms. Collazo wrote them anyway.

“If I didn’t write those reports, someone else would have,” she said. “One more stripe on the tiger doesn’t matter.”

Indeed, Cuban authorities cared more about tracking the dissidents than controlling what spies wrote for Internet Web sites. And over the years, agents posing as journalists wrote thousands of disparaging stories about human rights, health care, education, transportation and other topics.

They say that gave them credibility among Mr. Castro’s enemies, though not all agents cared about the truth.

Nestor Baguer, a journalist who began spying for state security police in 1960, said he often wrote lies, but only lies that the Americans “would swallow.”

So when a fellow reporter suggested a bogus story about 100,000 Cubans swarming a street corner in the eastern town of Manzanillo to protest apartment evictions, Mr. Baguer scolded him, calling it a ridiculous idea.

Not that many people can possibly fit on a street corner, he said.

“Tell the lie, but in a different way,” he advised.

Mr. Baguer, 82, kept his identity secret for more than four decades, emerging in April to testify against the political opposition and to reveal that he was actually Agent “Octavio.”

Just weeks earlier, U.S. officials in Havana allowed him to help lead a workshop on journalistic ethics. Thirty-four independent reporters, including an unknown number of spies, attended.

American media organizations have also been duped over the years, occasionally quoting dissidents who were actually spies. One U.S. official estimated that a third of all supposed dissidents and independent journalists were spies.

But, the official added, “We will continue on. We’re in the idea business. And we feel our ideas are strong enough to carry on.”

Cuba’s political system, on the other hand, “breeds” fear, repression, spies and informants, he said. “This society is built around the idea that the government has information on every aspect of your life – and it does. …You have the potential to be ratted on by anybody.”

Hidden cash

Cuban authorities are unapologetic and say they uncovered evidence of payments to the political opposition while searching dissidents’ homes in March.

They allegedly found $13,660 hidden in the lining of a suit belonging to independent journalist Oscar Espinosa. Cuban Foreign Minister Felipe Pérez Roque said the money came from CubaNet, an AID-financed Web site that distributes news about Cuba.

A CubaNet editor confirmed to The Miami Herald that $7,154 was sent to Mr. Espinosa, but said AID wasn’t the source. The money came from other CubaNet funds and the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders, she said.

Mr. Espinosa was sentenced to 20 years in jail.

Some dissidents, for their part, are increasingly reluctant to accept U.S. help, despite their great needs. Others are undeterred.

Mr. Roca said he’ll continue inviting Cubans to join the opposition, even if they turn out to be spies.

“If they are agents, that’s their problem,” he said. “They’ll have to respond to history.”