I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on July 10, 1997.

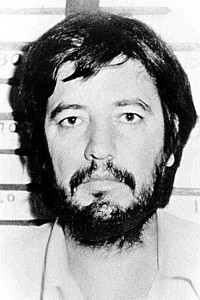

GUAMUCHILITO, Mexico – To U.S. agents, he was a ruthless monarch of the drug trade, flooding American streets with cocaine. But to his many friends and relatives, Amado Carrillo Fuentes was a kind soul who loved his family, baseball and enchiladas, drenched in his favorite spicy red sauce. “He loved his children very much and wanted them to get ahead and do well, especially in school,” said Mr. Carrillo’s nephew, Ernesto Carrillo. “Home was always home. He never brought home his problems at the office. ” In recent months, those “office problems” included being the subject of an intense worldwide manhunt. Mr. Carrillo, 41, wanted in Mexico and the United States, decided to check into a Mexico City hospital to try to change his appearance. But he died of heart failure July 4 afte r undergoing cosmetic surgery and liposuction, U.S. officials say.

Mr. Carrillo’s body eventually was expected to be flown home for burial in the Pacific state of Sinaloa. Scores of friends and family members in recent days have been streaming into the Santa Aurora Ranch near the village of Guamuchilito to pay their respects.

“Ever since Amado died, thousands of people have gone to the Aurora Ranch. And they all drive these 1997 Ram Chargers, Grand Cherokees, Chevrolet Suburbans, Lincoln Continentals – nothing like this cursed piece of junk,” said taxi driver Jesus Cazarez, thumping the steering wheel of his battered white and red 1974 Dodge Dart.

The Aurora Ranch, as long as a football field and surrounded by a 10-foot-high wall, is named after Mr. Carrillo’s mother, Aurora Fuentes. She and other family members spent two days in Mexico City trying to persuade military authorities to turn over Mr. Carrillo’s body.

A spokeswoman for Mexican Attorney General Jorge Madrazo said Wednesday that authorities still had not officially determined the identity of the body. But she said that it is highly likely that it is Mr. Carrillo’s. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has said the body’s fingerprints match those of Mr. Carrillo.

“How the Mexican government has acted has been very unfair.

They did the autopsies. The DEA confirmed that it’s Amado Carrillo’s body. Why have Mexican authorities been saying it’s not him? ” Ernesto Carrillo, 18, said in an interview at the Aurora Ranch. “We’re offended. ” Top DEA officials say they will remember him as one of the most powerful drug traffickers ever, a cunning individual accused of running a billion-dollar criminal empire.

But family members resent that view and say he had another side.

But family members resent that view and say he had another side.

He built a church and kindergarten in Guamuchilito, they say.

He routinely donated food, money, mattresses and sheets to orphaned children. He employed hundreds of farmers on his vast ranchlands in Sinaloa. He gave trucks and other equipment to little towns with strapped budgets.

And just before he died, his relatives say, he was talking about calling the mayor in neighboring Navolato to see how he could help out with some of the town’s public works projects.

“People shouldn’t consider him a bad person, but as someone just like everyone else,” his nephew Ernesto said. “Everyone in the world thought Al Capone was bad. But if alcohol had been legal in those days, Al Capone would have been a legitimate businessman.

“Legalizing drugs would make everyone the same, not good or bad. ” Many people here hold drug traffickers and other outlaws in great esteem.

In nearby Culiacan, the state capital, there’s a shrine to Jesus Malverde, a common thief who endeared himself to the poor as a sort of Robin Hood before being hanged in 1909.

Many others followed his example, helping to make Sinaloa a breeding ground for Mexico’s most powerful drug barons. At least 11 of the country’s top 20 traffickers – including Mr. Carrillo, the Tijuana-based Arellano-Felix brothers, Hector “El Guero” Palma, Juan Jose “El Azul” Esparragoza and Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman – were born in Sinaloa, according to the DEA.

“Sinaloa is to Mexico what Cali and Medellin are to Colombia,” said Phil Jordan, former head of the El Paso Intelligence Center, jointly run by the DEA, FBI and other agencies.

And it’s a vicious business, he said.

“These guys don’t rise to power by being choirboys,” he said.

“And to double-cross them is to sign your own death warrant. ” Mexican authorities, for instance, blame Mr. Carrillo’s organization for a number of deaths, most recently the killing of anti-drug agents Roberto Espinosa and Miguel Angel Vazquez. Their bodies were found in April in the back of a stolen 1995 Nissan Tsuru sedan.

But in Guamuchilito, villagers say they saw only kindness and generosity in Mr. Carrillo and his underlings.

The town has a population of 375, a general store slightly bigger than a walk-in closet, no stoplights and no police station.

Chickens skitter along dirt paths, children play in the shade of lush mango trees, and four-wheel-drive trucks rumble along the village’s four streets, none of them paved.

“When Amado came here, he was always friendly. He seemed to know everyone’s first name,” said a 19-year-old resident who requested anonymity.

“I can’t believe he’s dead. A lot of us around here feel that way. And some people are worried that now that he’s gone, the government will take away his ranches and a lot of farmers will lose their jobs. ” Mr. Carrillo’s traditional base was Ciudad Juarez, across the border from El Paso, but he had the ability to operate all along the international line, DEA agents say.

“He learned a lot from the Colombians,” DEA chief Thomas Constantine said in an interview. “He became an expert in technology. And he used all types of encryption devices. He had systems to give him privacy in all his communications. He was very sophisticated. ” U.S. law enforcement officials say Mr. Carrillo’s ability to compromise drug agents and government officials was another one of his strengths. He reportedly gave one Mexican mayoral candidate $4 million as a way of winning his loyalty, U.S. officials say. The candidate won.

Mexican authorities this year began stepping up the pressure on Mr. Carrillo. On April 22, for instance, police raided a home in Jardines del Pedregal, a posh Mexico City neighborhood. Mr. Carrillo was nowhere in sight, authorities say, but they did find mail addressed to one of his sons, Vicente Carrillo Leyva, 20.

No one was arrested, but police said at the time they would continue looking for both Mr. Carrillo and the son, who little more than a month earlier had purchased a bulletproof Mercedes Benz for $255,000.

Mr. Carrillo’s nephew, Ernesto, said family members aren’t mixed up in the drug trade and should be left alone.

“The government won’t let us lead normal lives,” he said. “And

even now that Amado Carrillo is dead, we don’t know what’s going to happen.

“We hope they leave us in peace. Like the Mexican saying, `With the dog dead, the rabies are gone. ‘ Unfortunately, I don’t think they’ll leave us alone. From what’s been published in the newspapers these days, the government says there are still some of our relatives who are involved in drug trafficking. ” As Ernesto Carrillo spoke, a constant stream of cars and trucks flowed into Aurora Ranch. They carried everything from red roses for the funeral to refreshments, and fuel for a generator at the ranch. Two men stood at the black metal gates, opening and closing them as the vehicles roared in and out.

Dozens of workers trimmed bushes, pulled weeds and mowed the lawn. Others prepared the crypt where Mr. Carrillo was to be laid to rest next to the body of his father, Vicente, who died more than a decade ago.

“He sure had a lot of friends,” said Mr. Cazarez, the taxi driver. “He also paid off a lot of people. Police, government officials.

“But he couldn’t bribe death. “