I wrote this article for NBC News (see original article).

HAVANA — Cubans endured grinding poverty, food shortages and crumbling streets during the rule of Fidel Castro. His critics say his legacy is a disaster, a country in ruins that will take years to repair.

Castro’s die-hard supporters reject such a dire view, recalling that his government wiped out illiteracy, boosted social equality and helped turn Cuba into a powerhouse in health, education and sports.

Castro made mistakes, these loyalists say, but never stopped fighting for a better world.

“In Cuba, we’ll miss him a lot, more than in any other place,” said Alexis Leyva Machado, a Cuban artist better known by his nickname, Kcho. “We’ve learned a lot from Fidel.”

Kcho, aka, Alexis Leiva Machado, is one of Cuba’s most famous artists.

Kcho, 45, stood outside his studio and exhibition hall, a former repair shop for buses in Romerillo. The neighborhood, he said, used to be one of Havana’s worst. Then he and other residents got together and started cleaning it up. They built parks where trash dumps once stood.

Castro stopped by one day and wrote the artist a note: “For Kcho, genius of culture and education, for the kindness with which he dedicates his life to the happiness of others.”

Kcho played down the compliment, saying, “I’ll tell you one thing: The genius is Fidel.”

“He went from being a lawyer to becoming a defender and savior of an entire country and an entire people,” he said. “The world needs people like Fidel who have the ability to teach people to dream and to make their dreams reality.”

Maria Antonia Figueroa is another unabashed Castro supporter. She said his legacy is the 1959 revolution, which distributed land to poor farmers and freed Cuba of U.S. government influence.

“We were the first free territory in Latin America,” said Figueroa, whose nom de guerre during the revolution was “the Doctor.” She was treasurer of the rebel organization known as the July 26 Movement.

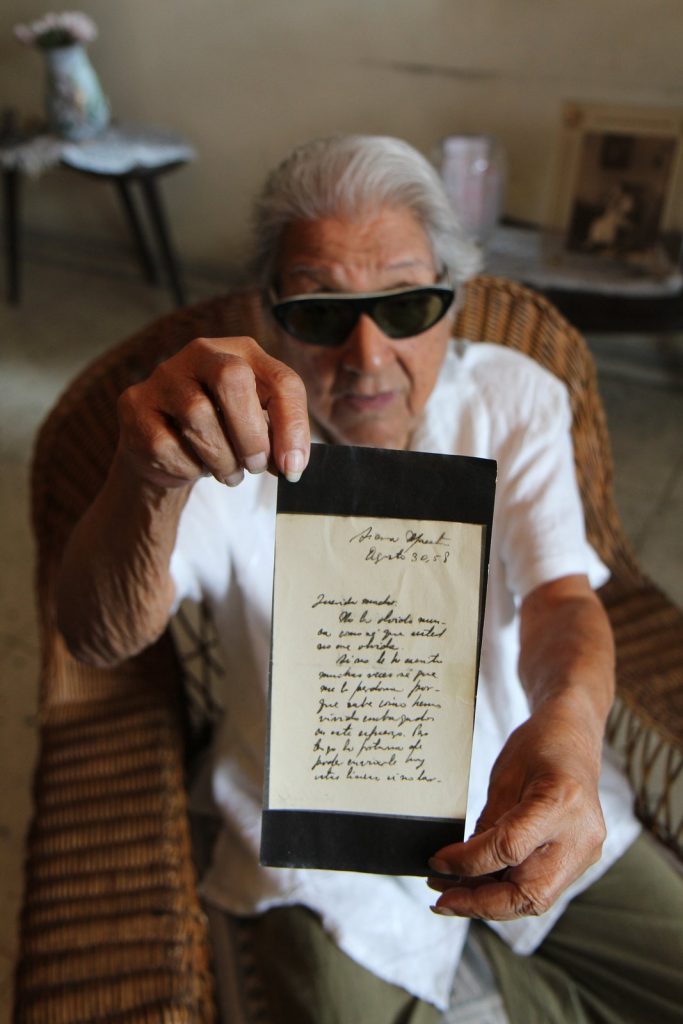

Maria Antonia Figueroa was treasurer of the rebel organization known as the July 26 Movement.

Now 97, Figueroa lives in on the second floor of a modest apartment building in Havana. On a recent afternoon, she sat reminiscing in her living room, adorned with Castro’s portrait.

She retrieved a copy of a letter of thanks that Castro wrote her from his secret hideout in the Sierra Maestra mountain range during the revolution. It was dated Aug. 30, 1958.

“It’s a treasure for me because it’s his handwriting and from the Sierra Maestra,” she said. “When it’s my time to die, I’ll be happy, having given my little grain of sand for this grandeur called Revolutionary Cuba, Communist Cuba.”

Cuban journalist Marta Rojas is another Castro supporter. She described the Cuban leader as a “great politician” who was well versed in law, history and science.

“Any way you look at it, he was a genius. They say that geniuses do what they can and not what they want because their minds are filled with too many ideas to carry out.”

Marta Rojas is a journalist and writer who covered Fidel Castro’s trial in 1953 for his failed attack on the Moncada Barracks.

Rojas, 84, has followed Castro since July 1953 when he attacked the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba, the country’s second largest city.

Castro was captured after the failed attack, which marked the start of the revolution. Three months later, Rojas watched as Castro used his trial to condemn the government of then-dictator Fulgencio Batista as corrupt and unjust.

Castro spoke for four hours, ending with the words, “History will absolve me.”

Rojas believes that Castro spoke the truth that day. “History has already absolved him,” said the writer, who lives in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood.

Rojas, who has spent the last several decades writing historical novels, pointed out that Castro’s government gave free schooling to millions of Cubans.

She earned several diplomas herself, but hung only one of them on the wall.

Marta Rojas is a journalist and writer who covered Fidel Castro’s 1953 trial

“I don’t like diplomas,” she said. “I keep this one because it has Fidel’s signature. The others I stuff in a suitcase.”

Castro took power on Jan. 1, 1959. The U.S. wanted to oust him and sponsored the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961. Castro quickly aligned with the former Soviet Union and asked the Soviets for weapons.

The Soviets proposed equipping Cuba with medium-range ballistic missiles. That brought the U.S. and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war in 1962.

Photographer Ernesto Fernández, 75, recalled that Castro stopped by the Revolución newspaper in Havana and declared that he wanted to “shoot down any plane that flew over Cuba.”

Ernesto Fernandez, 75, gained fame for photos taken during the Bay of Pigs conflict.

At dawn the next day, Fernández said he and other journalists went to an anti-aircraft site near Havana and prepared to photograph the action. Fidel was there.

Fernández said a soldier told Castro, “But commander, if the planes come this way, we can’t shoot them because the barrage of gunfire will fall over Havana.”

“Fidel says, ‘what do you mean you can’t shoot the planes?'”

The soldier replied, “Unless you give the order, I won’t shoot them.”

“So Fidel says, ‘Let’s go pick up some rocks and bring the planes down with stones,'” Fernández said.

“It was a joke, but no one could imagine that at that moment, when it seemed the world was going to end, he’d say, ‘No, let’s go pick up rocks.'”

The crisis subsided after the Soviets agreed to remove their missiles and the U.S. promised not to invade Cuba.

The U.S. continued trying to undermine Castro, imposing harsh economic sanctions. But the Cuban leader survived.

“He is the whole island”

Castro had a string of titles: head of state, president, chief of the Communist Party. But most Cubans simply called him “Fidel.”

He had sweeping authority, but told his followers: “The leaders of this country are human beings, not gods.”

Still, there was no doubt Castro ruled supreme.

“Castro is at the same time the island, the men, the cattle and the earth,” French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote. “He is the whole island.”

Few Cubans criticized Castro publicly while he was in power. Many spoke about him in hushed tones and avoided saying his name out loud, tugging on an imaginary beard instead.

Authorities regularly arrested Cubans who criticized the government during Castro’s rule. Methods of control included beatings, detention, public shaming, and long prison sentences.

Dissident Vladimir Alejo Miranda is among those who has been arrested. His chest is emblazoned with a tattoo that reads: “Down with Murderer Fidel.”

He said he got the tattoo so that whenever he’s taken into custody — whether it’s jail, the police station or a hospital — people will see the tattoo “and I’ll show once again that I’m against the Castros.”

Castro’s supporters say most people supported the Cuban president. During elections, he routinely drew 96 or 97 percent of the vote. Critics say it’s impossible to know how many people would have voted for Castro if they weren’t pressured or if they had other choices.

What’s certain is that Castro stirred deep passions. A 1998-99 U.S. government-financed survey of 1,023 recent arrivals from Cuba asked respondents to name the leader they hate the most. Castro came out on top.

“He bothers some people. Some people have a love-hate relationship with him. Not me,” said Rebeca Chávez, a Havana filmmaker who has helped produce documentaries about Castro.

Rebeca Chavez is a filmmaker who has made several documentaries about Fidel Castro and the Revolution.

Alvarez was making a documentary called, “The Necessary War,” which told of Castro’s preparations to fight then-dictator Fulgencio Batista. Alvarez mentioned to Castro that an old man who lived nearby had met José Martí, a national hero who fought for Cuban independence, when he came ashore decades earlier.

Castro insisted on meeting the man, named Salustiano Leyva. And as the cameras rolled, Castro interviewed Leyva. The man said he was only 11 when Martí arrived, but said he remembered that day well.

Trademark cigar in hand, Castro continued asking “questions and questions and questions,” Chavez said.

But Leyva had poor eyesight and didn’t realize he was talking to Castro.

When the conversation turned to the revolution, Leyva said, “I’d die for Fidel.”

Later, Chávez said, “Salustiano starts to realize who that man was. And he suddenly asks, “Are you Fidel?”

“Yes,” Castro replied.

“It was very emotional,” Chávez said.

She said the bitterness that some Cubans feel “does not allow them to see the brilliance of this man.”

Castro “was not a perfect man,” she said, but gave Cubans “a sense of dignity, a sense of belonging.”

By 1985, Castro had given up smoking cigars, Ronald Reagan was president of the United States and the Cold War was raging. The former Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and economic turmoil quickly hit Cuba.

Times were so tough that some people ate breaded grapefruit rinds instead of meat. Castro’s critics predicted the government’s fall, but it managed to stay afloat.

In July 2006, Castro fell ill after a sudden intestinal ailment and dropped out of sight. Cuban lawmakers formally transferred power to his younger brother, Raul, in February 2008.

In his letter of resignation, Fidel Castro wrote, “This is not my farewell to you. My only wish is to fight as a soldier in the battle of ideas.”

After retirement, Castro was thought to spend most of his time at a comfortable, yet far from palatial home. Anti-Castro blogs published satellite photos of the home, which had a living room, dining room, kitchen, library, swimming pool and garden.

Castro’s critics accused the Cuban leader of stashing money in foreign bank accounts, but his supporters denied it.

“Fidel never sought personal benefit,” said Arsenio Dávila García, 79, one of only four surviving ex-combatants who are ranked as “commanders” of the revolution. The other three commanders are Ramiro Valdés, Efigenio Ameijeiras and Raúl Castro, the current president of Cuba.

Black-and-white photos on the wall of his home show Dávila Garcia and other rebels with shaggy beards. They were nicknamed the Barbudos, or Bearded Ones.

Fidel Castro was “extremely honest,” Davila Garcia said.

Former Olympic athlete José Sotomayor said Castro will be remembered “as a great man, like few men are remembered in the world.”

“I think Fidel —has been a man without precedent, his intelligence, his ability, his desire to unite all peoples and fight against poverty, and for brotherhood, for harmony,” said Sotomayor, 47, who holds the world high jump record of 2.45 meters (8.038 feet).

“I think his example will always endure,” he said. “For everything he’s done for us, he’ll always be in our memory.”

Castro was a “political tiger” with a tremendous ability “to find a cause he believes in and fight and fight and fight,” Cuban blogger Harold Cárdenas said.

His biggest weakness, his Achilles’ heel, was his inability to create a prosperous economy, Cárdenas said.

Too many Cubans, he added, don’t know about – or don’t want to admit – mistakes that Castro made.

“Not addressing his successes and failures in an objective way hurts him. And I think that at some point, we Cubans have to look at Fidel in an objective way,” said Cárdenas.

Many Cubans expect change to come with Castro’s death, but Osmani Díaz, 43, said he hopes the Cuban revolution lives on.

Batista’s troops killed his grandfather in the 1950s.

“He was accused of helping Fidel, of giving food and some supplies to Fidel and he was taken and burned alive,” said Díaz. Today he works as a guide at La Plata, Castro’s former secret command post in the Sierra Maestra.

“I think Fidel planted the seed and the roots are there so that this goes on,” he said. “The promise of the revolution is in our hands. I hope other Cubans think like I do so that the revolution can be saved.”