I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Nov. 2, 2001.

Lack of food, shelter hits women, children especially hard

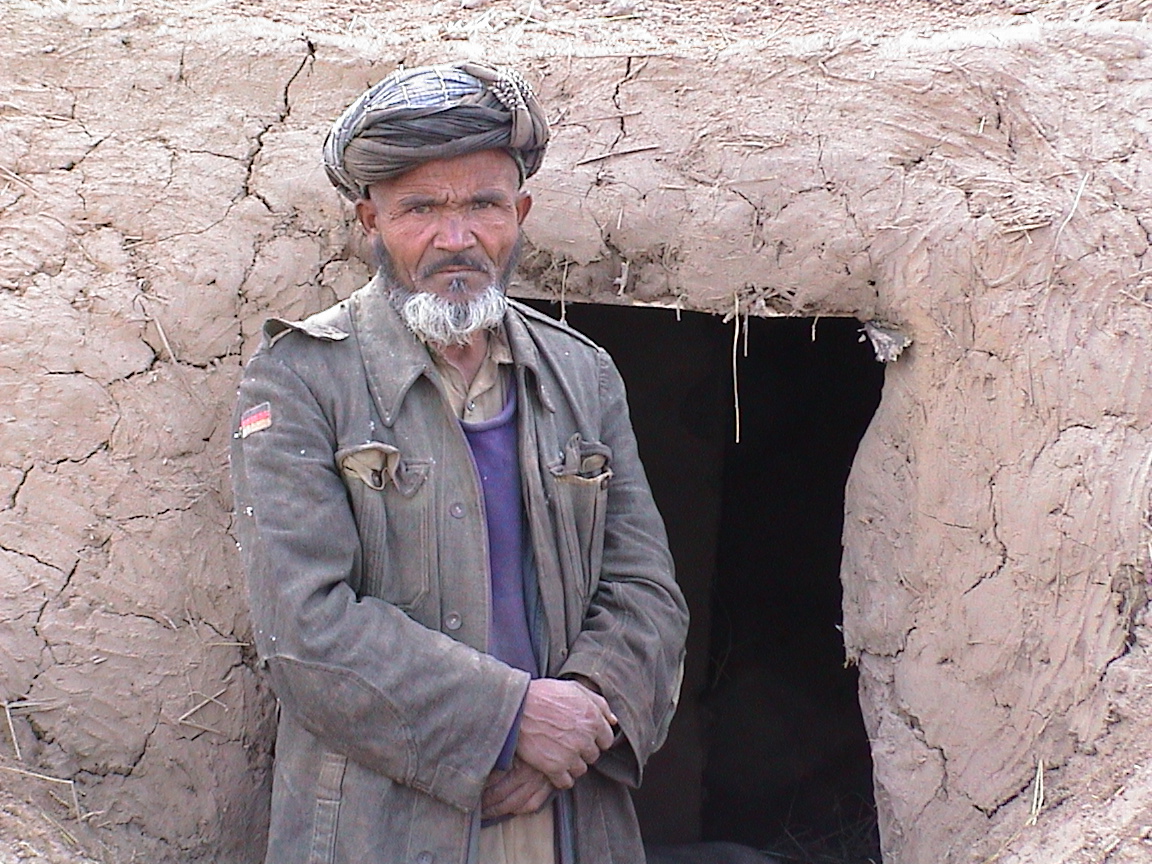

Abdul Samad came back from town last year to find his son sprawled on the frozen ground.

Winter took the boy, plain and simple, he said.

“Cold killed him. Hunger, too.”

Now, with another winter two weeks away, Mr. Samad is bracing for the deadly onslaught.

Relief workers say as many as 7.5 million Afghans are at risk of starving, freezing to death, or dying of disease in the coming months. It’s a sad showdown pitting subzero temperatures and savage 90-mph winds against centuries-old survival skills and the raw human spirit.

The most vulnerable are those living in makeshift camps after having fled their homes to escape civil war, drought, and U.S. airstrikes.

One such camp is Qumqushlaq, near the town of Khoja Bahauddin in northern Afghanistan. Qumqushlaq is a patchwork of tents, caves, and mud-brick shelters that begins along a riverbank and stretches for miles.

Finding a mother or father who lost a child during last year’s brutal winter isn’t hard. Half the children are malnourished, relief workers say, and one in three dies before age 5 in the camps.

Like the other parents, Mr. Samad brought his children to Qumqushlaq after the Taliban took over his village.

He is a working man who knows about sweat and sacrifice. He survives without running water and electricity. He knows how to build sturdy mud walls, much like his ancestors did. But he cares little about modern ways and hasn’t bothered to keep track of his own age; 27, he figures, although his graying beard and weathered face betray that guess.

Mr. Samad, his wife and two children live in a crude shelter fashioned from straw mats and mud. After 3-year-old Ahamad died last winter, he began sending his remaining children to a mosque on cold nights.

“It’s warmer there,” Mr. Samad said. “But I’m not sure that will be enough to save them.”

He also worries about his mother, Gulbi Kamper. So a few months ago he dug a hole for her to live in, and he covered it with straw.

“We built like this because of the cold and the wind,” he said.

‘The need is enormous’

Qumqushlaq and other camps near Khoja Bahauddin are worse than most, said Farshad Rastegar, executive director of Relief International in Los Angeles.

“People don’t have enough food or shelter,” he said while visiting one camp. “The need is enormous.”

No one knows for sure how many Afghans died in camps nationwide last year, but some aid workers say it probably ran into the thousands. Camp dwellers at Qumqushlaq say 200 to 300 people died there.

“If the foreigners don’t help us, the number of deaths could rise this year,” said Abdul Quahar, 30, a mason when he can find work.

Many of last year’s dead were children and babies. Dozens of women died, too; Afghanistan has the world’s highest mortality rate for pregnant women.

“Any simple complication during pregnancy is likely to lead to something serious,” Mr. Rastegar said.

Rooze Mohammad, who moved into the camp last year, prays that winter doesn’t take any more of his children. His 5-year-old daughter, Shafiqa, died last year.

“I had only a tent,” he said. “It was cold and windy. Snow came into the tent and made it wet.”

This year Mr. Mohammad used his bare hands to build a wall of mud around a straw-mat shelter. He, his wife, and six remaining children live there.

“If Allah allows, we’ll stay here until the Taliban leave our village,” he said.

Asked how he will survive, he pointed to the sky. “The Americans must drop more food,” he said.

A lone plane flew by several weeks ago, leaving packets of biscuits, sugar, rice, cake, and bread, he said. “We ate it. It was very good. But the plane came only one time.”

Conditions are slightly better at Nowabad camp, an hour’s drive away. The camp isn’t along a river, so it’s drier. Digging shelters in the ground is easier.

Shelter or food

Still, the choices are excruciating.

“People want to get ready for winter. They want to build. But many can’t because they’re out of food. So they sell their construction materials to buy something to eat,” said Abdul Baqui, 48.

He is an elder at the Nowabad camp, home to about 1,000 people. Sixty women and children died there last winter. They were buried on a nearby slope. Poles and ribbons mark their graves.

Opposition soldiers are stationed at a tank a few hundred yards away. Sometimes they fire over the camp and into the hills where Taliban troops hide.

Paying the price

Not many young men are at the camp. Most are on the front lines. Mr. Baqui has done his share of fighting – and paid the price.

The last time he tangled with members of the Taliban , they grabbed him, held him down and repeatedly drove a truck over his leg. He survived. His right leg didn’t, he says, tugging on an artificial limb.

No matter. He dreams of fighting the Taliban again.

“With America’s help, we can capture our village,” he said. “Then we will return.”

Even before the United States began bombing the Taliban last month, Afghanistan faced a humanitarian crisis, United Nations workers say.

Fighting between the ruling Taliban and rebels – along with a lingering drought – had left as many as 6 million people in need of aid.

The U.S. attacks drove even more people from their homes, pushing the number of Afghans in need to as many as 7.5 million, relief workers say. Seventy-percent of them are women and children.

Pregnant women face particular danger; as it is, one Afghan mother dies during childbirth every 30 minutes, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Relief workers also worry about the 600,000 to 700,000 people who live in north-central Afghanistan and are likely to be stranded by winter weather. So they plan airdrops of food in those areas.

Getting aid into Afghanistan by land has been next to impossible, although neighboring Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have begun to loosen border restrictions, said Khalid Mansour, a spokesman for the U.N.’s world food program.

Even before the U.S. bombing campaign began, U.N. workers had started a project to help 90,000 displaced Afghans. But security and staffing problems and fuel shortages plagued the project, U.N. spokeswoman Stephanie Bunker said.

“Everything started to fall apart,” she said.

Losing a son

Which isn’t good news for the camp dwellers. Take the case of Shamusuddin, a 25-year-old wheat farmer.

Last year, he and his family sought refuge in a hole in the ground. But the snow and ice were too much for his 1-year-old boy, Gulbuddin, who died.

He’s hoping his 4-year-old daughter doesn’t meet the same fate this year.

“I fear for the winter,” he said. “If the snow comes again, it will be very hard.”

Staff writer Lee Hancock in Islamabad, Pakistan, contributed to this report.