I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on May 12, 1996.

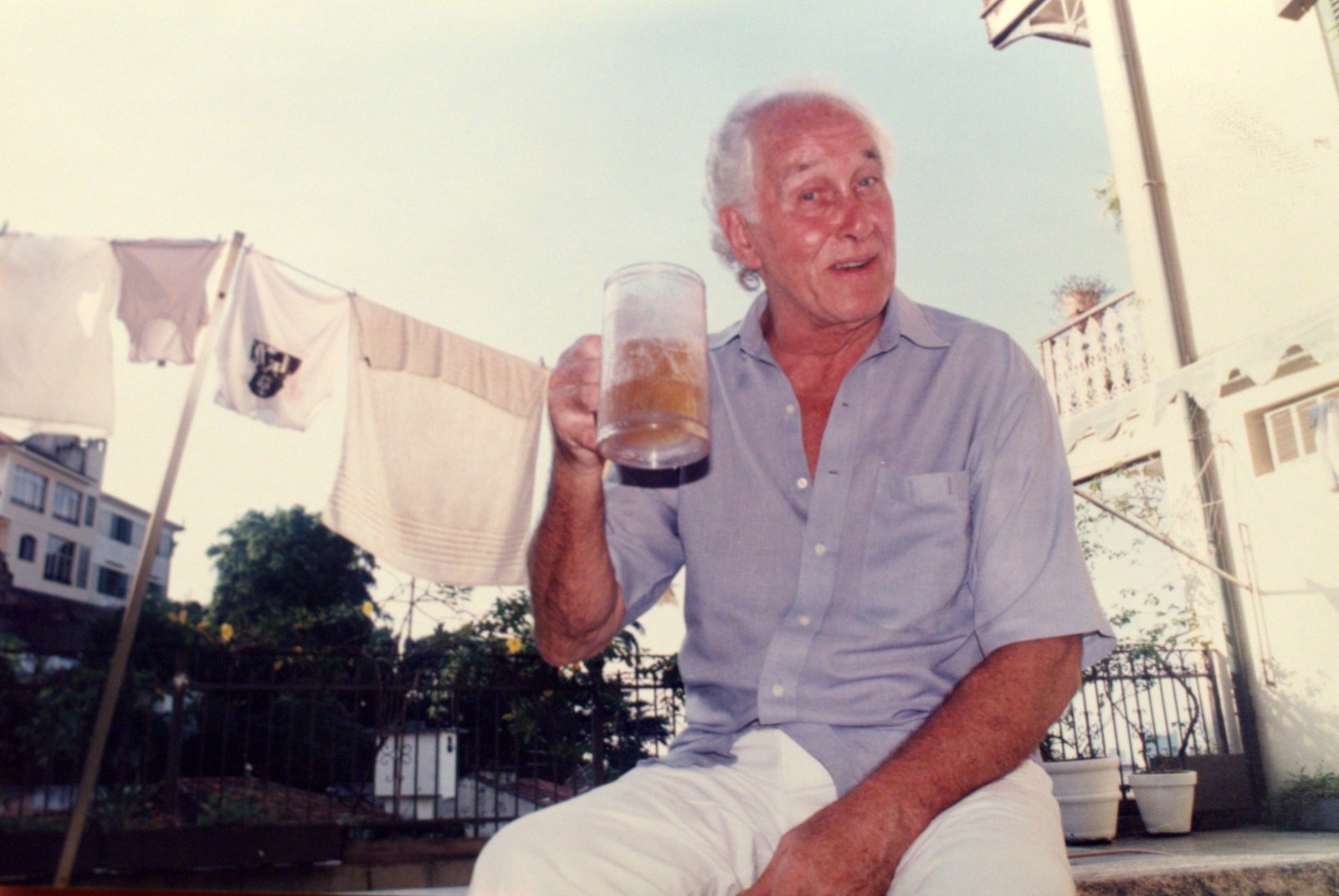

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil – One of the world’s most notorious fugitives is living out his golden years in sunny Brazil, sipping frosty mugs of beer, spinning tales and lounging poolside.

“I’ve wiped the slate clean,” says Ronald Biggs, who helped pull off Britain’s Great Train Robbery, one of the most sensational crimes in history. “I’ve done my time.” British authorities see it differently, saying Mr. Biggs is an outlaw who served less than two years of a 30-year sentence for helping rob a mail train stuffed with cash in 1963.

He broke out of prison in 1966 and went on the run, using phony documents and plastic surgery to outfox Scotland Yard.

He’s been in Brazil since 1970. Police haven’t been able to touch him because there has been no extradition agreement between the United Kingdom and Brazil. But now a treaty has been signed and need only be approved by lawmakers from both countries. And although the British haven’t yet said they’ll seek extradition, the former bandit, now 66, vows to fight any effort to return him.

“I’ve never been a villain. Ronnie Biggs is nothing more than somebody who runs out the back door as the cops are banging on the front door. There are obviously people who will say, `Hang that man from a bloody noose.’ But I think they are far outnumbered by people who say, `Give the old bugger a go. He’s been on the run all these years.’ ”

“I’ve never been a villain. Ronnie Biggs is nothing more than somebody who runs out the back door as the cops are banging on the front door. There are obviously people who will say, `Hang that man from a bloody noose.’ But I think they are far outnumbered by people who say, `Give the old bugger a go. He’s been on the run all these years.’ ”

Many Brazilians agree. They’ve taken a liking to the quirky renegade who quotes Shakespeare, writes poems about prison guards and once recorded a song with the punk band the Sex Pistols.

“He’s a thief, but at least he’s a fun thief,” Rio waitress Alessandra Rico said.

Even some of the fugitive’s old enemies in England are grudgingly sympathetic.

“The money we’d spend keeping him in prison wouldn’t achieve anything. It wouldn’t deter people,” said Jack Slipper, a former chief detective at Scotland Yard. “If a man gets away from the police and hides in a bloody cave somewhere, leave him in his cave.”

Still, he warned, Mr. Biggs “is a cunning boy” who shouldn’t be underestimated. And if he returns to England to flaunt his freedom, “rubbing it in everyone’s faces . . . there’s only one place for him: prison. If he comes back, he should serve some time. Four or five years.”

Mr. Biggs snarls at the idea. Already, he says, one British intermediary tried to persuade him to give up in exchange for a “nominal” three-year sentence.

“I said, `Look, pal, I wouldn’t go back for nominal sentence of three hours.’ It would be totally unjust. In plain terms, it would be a crime.”

Mr. Biggs got his start in thievery by stealing a box of pencils and was soon a regular at London jails. He said he stole because he didn’t want to wind up like his father, working hard for low wages.

“My father had two jobs. He would arrive home late at night, smelling of honest sweat. He liked to declare, `Hard work never killed a man,’ but I’m sure it killed him in the end. I thought there must be something better in life.”

Mr. Biggs said he learned about plans to rob the Glasgow-to-London mail train from a friend and former prison mate, Bruce Reynolds.

Mr. Biggs’ role in the Aug. 8, 1963, crime was to recruit a backup driver for the train and to operate a radio during the heist. The job netted 2.6 million pounds, equal to more than $30 million at today’s rates. Of that, only 343,448 pounds was ever recovered, according to the Guiness Book of Records .

Mr. Biggs’ share, filling two army bags, was about 147,000 pounds, equal to more than $2 million today. He stashed away most of the loot but was captured less than a month later. His big undoing: His fingerprints were found on Monopoly cards and a tomato sauce bottle at the gang’s hideout, a farm outside London.

In all, 14 of the 18 people who helped plan or carry out the crime were captured. Most were convicted and imprisoned.

At sentencing, Judge Edmund Davies called Mr. Biggs a “specious liar” and slapped him with the maximum – 30 years. “Twice the amount you might get for bumping somebody off, for Christ’s sake,” the convict later grumbled in his memoirs.

At sentencing, Judge Edmund Davies called Mr. Biggs a “specious liar” and slapped him with the maximum – 30 years. “Twice the amount you might get for bumping somebody off, for Christ’s sake,” the convict later grumbled in his memoirs.

Mr. Biggs was sent to Wandsworth Prison in South London, but he didn’t stay put for long. With help from accomplices on the outside, Prisoner 2731 plotted an escape. On July 8, 1965, he and a friend scurried up a rope ladder that was thrown over the prison wall and hopped to the roof of a waiting furniture van, which sped off.

Those were the days, he said.

“I was full of the joys of spring. Make that, full of the joys of being sprung.”

His life on the run – chronicled in his 1994 book, Odd Man Out – had begun.

First he journeyed to France for plastic surgery. Once the swelling went down and the 140 stitches were removed, a friend painted black sideburns on his face to hide the scars. By December 1965, the elusive Mr. Biggs was bound for Australia, traveling under the name Terence Furminger.

He sent for his wife, Charmian, and two children the following summer. They took a new name, the Cooks, and lived peacefully, eventually settling in Adelaide. But the police soon caught up with them, and Mr. Biggs took off for South America – without his children or wife, who later divorced him.

Once in Brazil, Mr. Biggs worked as a carpenter by day and caroused by night.

In February 1971, he got terrible news: His eldest son, Nicholas, had been killed in a car accident in Australia. Mr. Biggs said he agonized over turning himself in. But he got over the shock, gulped down two big swigs of brandy and decided to continue life on the run.

By then, he said, his share of the loot was almost gone, and he needed money. So when a British newspaper, the Daily Express , offered to buy his story, he agreed. But on the third day of interviews and photo sessions, his old rival Jack Slipper, former chief of Scotland Yard’s famous detective team, the Flying Squad, stepped into the Rio hotel room.

“Hello, Ronnie,” he said. “I think you know who I am. I certainly know who you are, and I’m arresting you.”

Mr. Biggs was taken into custody and appeared headed for England. But a Brazilian court released him. The reason: He was going to be the father of a Brazilian child and couldn’t be extradited.

His girlfriend, Raimunda Nascimento de Castro, was pregnant at the time. She quickly became a celebrity of sorts and used her newfound status to launch her striptease career in Europe.

His girlfriend, Raimunda Nascimento de Castro, was pregnant at the time. She quickly became a celebrity of sorts and used her newfound status to launch her striptease career in Europe.

Their child, Michael, was born in August 1974. He also went into the entertainment business, joining the Magic Balloon pop music group at age 6. The band, composed of children, was a success, selling millions of records.

“For three years, we toured nonstop,” said the younger Biggs, now a solo artist. “We had our own plane and were flying every day. I’ve got more flight hours than a lot of pilots. We were all burned out by the time we were 12.”

Michael Biggs’ early celebrity status stirred sympathy for his father in 1981 when the fugitive was kidnapped.

The pay-for-hire captors, led by a burly Scotsman named John Miller, were determined to return Mr. Biggs to England. They gagged him, blindfolded him, crammed him into a sack and flew him to a port in northeast Brazil. Then he was put on a 62-foot yacht bound for the Caribbean island of Barbados, a member of the British Commonwealth.

Michael Biggs, still just 6, went on Brazilian TV with a desperate plea, saying Scotland Yard may want his father, “but I need him more.”

A Barbados court released Mr. Biggs, citing procedural errors in his capture, and soon the former train robber was heading back to Brazil aboard a Lear jet stocked with champagne.

“BIGGS ELUDES THE YARD AGAIN!” one newspaper blared.

Brazilian authorities have said they won’t extradite Mr. Biggs as long as no treaty is in place, and they point out that he has no criminal record in Brazil.

The ex-con now lives in a house he remodeled with the help of earnings from his son’s Magic Balloon years. The home, perched on a Rio hillside, is complete with white marble floors and a 13-by-22-foot slate-lined swimming pool.

The ex-con now lives in a house he remodeled with the help of earnings from his son’s Magic Balloon years. The home, perched on a Rio hillside, is complete with white marble floors and a 13-by-22-foot slate-lined swimming pool.

It is here that the former thief works his charm on visitors, including tourists paying as much as $75 each to slug down ice-cold beer, hear stories and pose for pictures – “The Biggs Experience,” one departing journalist called it.

“This gives me income as well as fun,” Mr. Biggs said. “The better the party, the better the return.”

During these visits, he pushes his I’m-no-crook cause. He urges visitors to “spread the gospel.” And the fan mail pours in, some letters arriving with nothing more than “Ronald Biggs – Rio de Janeiro” scrawled on the envelope.

And while some people resent him making money off past misdeeds, he says he’s suffered while on the run and deserves to remain free.

“I’ve lived an honest life,” he said, “I mean, as honest as the next man.” Opening another beer, he acknowledged that he’s seen plenty of good times.

“Weird and wonderful things have happened while I’ve been on the run. I must say I’ve been blessed with some phenomenal good luck.”