I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Nov. 30, 1995.

MEXICO CITY – They’re savvy enough to penetrate government’s highest levels and ruthless enough to eliminate almost any adversary. They employ a virtual army, 350,000 strong. And they’ve got money, lots of it, earning as much as $28 billion per year, by one government estimate. Never before have drug cartels posed such a grave threat to Mexico’s security, top law enforcement officials say.

“Modern war, the war of the century, is the war against drugs and organized crime,” Attorney General Antonio Lozano said.

But as the authorities plot against the enemy, they find it’s a many-headed monster. They can’t beat the traffickers without cleaning up entire police agencies, the courts and prosecutors’ offices.

They’re stuck with a deeper problem: Corruption has seeped into almost every crack in the judicial system, posing yet another challenge to President Ernesto Zedillo.

As if political and economic turmoil weren’t enough, the justice system is in shambles. Mr. Lozano says that “a high percentage” of his employees – and that could mean hundreds of police agents – are probably on drug traffickers’ payrolls.

Complicating matters, politics – and not fairness or equity – often influences whether justice is served.

“Structurally, nothing’s changed,” said Rafael Rivera Bonilla, head of a Mexico City human rights group for former jail inmates. “Justice is still used for political purposes.”

Changing the judicial system is a daunting task. Bribes, influence peddling and other corrupt practices have become such fundamental parts of the process that some observers fear that removing them actually would destabilize the government.

Sensitive system

“The government can’t afford to crack down,” said Peter Lupsha, a University of New Mexico political scientist who studies the drug trade. “The system’s too wobbly.”

At the same time, the government can’t ignore crime and corruption, Mr. Lupsha and other critics say. Without a determined, prolonged crackdown, crime could wipe away any future economic and political gains.

Society could become so lawless that trade and commerce will be paralyzed. Criminals could become so vicious and so violent that the government will forget about human rights entirely, giving police the freedom to beat up, torture and kill just about anyone they want.

Society could become so lawless that trade and commerce will be paralyzed. Criminals could become so vicious and so violent that the government will forget about human rights entirely, giving police the freedom to beat up, torture and kill just about anyone they want.

Or Mexicans could simply rebel, having lost all faith and trust in authority and the government.

“Your worst-case scenario is civil war,” said David Jordan, a former U.S. ambassador to Peru who testified this year before a Senate committee studying corruption in Mexico.

Mexican officials call such talk alarmist, but almost everyone agrees that the government must bring about reform and get the drug cartels under control.

Mr. Zedillo describes drug trafficking as the No. 1 threat to Mexico’s health and security.

“Drug trafficking is a terrible enemy of our whole society,” he said in a September speech.

Clamping down on the traffickers and cleaning up the justice system won’t be easy, he conceded. “It is an arduous and prolonged task.”

Traffickers’ growing financial clout is one of the many obstacles. The cartels are believed to hand out as much as $500 million in bribes per year, more than double the attorney general’s annual budget, according to a National Autonomous University of Mexico study.

In another study, Manuel Fernando Badillo, a secretary of defense official, estimated that drug traffickers employed 350,000 people and generated from $26 billion to $28 billion in 1992 and 1993.

U.S. worries

“Mexico has definitely become the premier player in the smuggling of narcotics into the U.S.,” said Phil Jordan, director of the El Paso Intelligence Center, jointly run by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI, the Customs Service and other agencies.

U.S. authorities are worried about the cartels’ growing influence, but encouraged by the Mexican government’s anti-drug efforts.

“The sincerity of the Mexican government has never been greater,” Mr. Jordan said.

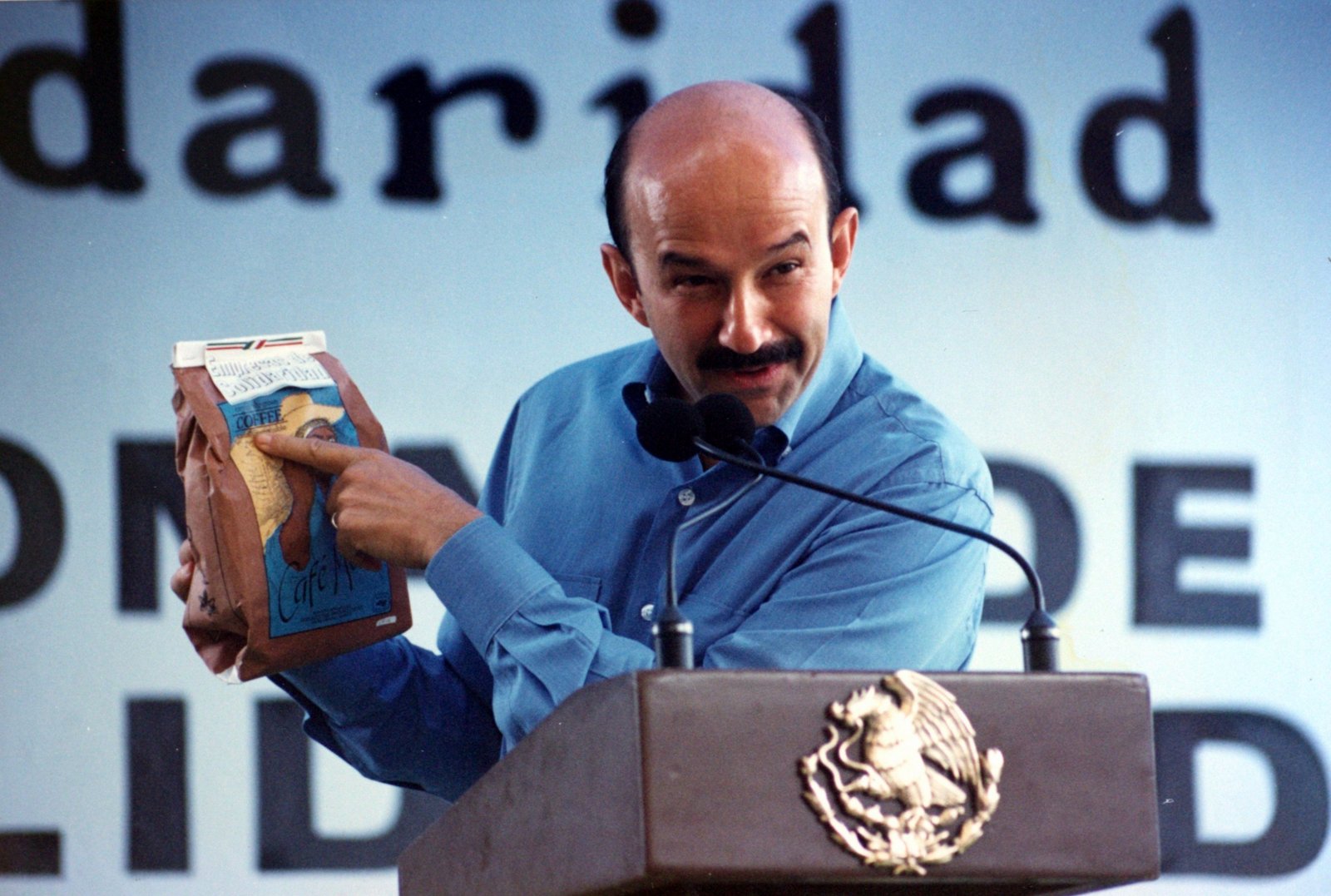

But the challenges are daunting. Some government officials find it impossible to resist taking huge bribes or using their public positions to pile up immense riches. Mexican authorities cite the case of Raul Salinas de Gortari, the older brother of former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari.

But the challenges are daunting. Some government officials find it impossible to resist taking huge bribes or using their public positions to pile up immense riches. Mexican authorities cite the case of Raul Salinas de Gortari, the older brother of former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari.

Swiss authorities arrested his wife, Patricia Paulina Castanon and her brother Antonio on Nov. 15 after they allegedly used fake documents to try to withdraw money from Raul Salinas’ secret bank accounts, containing nearly $84 million.

Raul Salinas says he’ll prove the money is legitimate. But Mexican investigators are skeptical, saying they find it hard to believe that Mr. Salinas saved so much money while earning $192,000 per year as a government employee.

`Ant’ corruption

A less dramatic, but important, challenge for Mexican authorities is what’s known as ” hormiga ” or “ant” corruption. It’s the small, everyday graft: The $4 bribe a motorist pays for running a stop sign, the $16 for a driver’s license.

Seemingly insignificant when compared to drug bribes, it adds up fast. Thousands of police officers, building inspectors and low-level bureaucrats collect bribes every day. If collected legally as fines and fees, all that money could pay for higher wages and better equipment, critics point out. Instead, it’s lost, tucked away in someone’s pocket.

Raul Garcia, 42, a former Mexico City police officer, says he didn’t realize just how pervasive hormiga corruption was until he left the police academy.

Raul Garcia, 42, a former Mexico City police officer, says he didn’t realize just how pervasive hormiga corruption was until he left the police academy.

He says his supervisors taught him all he needed to know: Protect your friends. Don’t snitch. And after a day of collecting bribes, share the proceeds with your boss.

“It’s an enormous stew of corruption,” Mr. Garcia said. “You pay and you charge for everything. You pay if you’re late to the office or if you want a promotion. You collect bribes to pay what your bosses demand. You’re forced to be corrupt.”

Some say the country’s economic situation – unemployment has soared since a devaluation of the peso in December – only makes corruption more unmanageable.

“The economy’s in a bad way,” said a police aide who identified himself only as Juan M., assigned to help collect $20 bribes from motorists whose cars were towed. “If someone wants to corrupt us, we’ll let them. With pleasure.”

Voter anger

Voters are increasingly angry about corruption, and the government knows that.

Mr. Zedillo began a cleanup campaign Dec. 1, 1994, the day he took office. He was the first president ever to name as attorney general a member of an opposition political party. Mr. Lozano belongs to the conservative National Action Party, or PAN. The president cites Mr. Lozano’s appointment as irrefutable proof of his sincerity.

“Let’s see who can think of something more dramatic than what I’ve done,” he said.

Mr. Zedillo also replaced the entire Supreme Court, boosted standards for joining the court cut its size from 26 to 11 members. Before the change, “it looked more like a Congress than a court,” one official said.

Among the other advances:

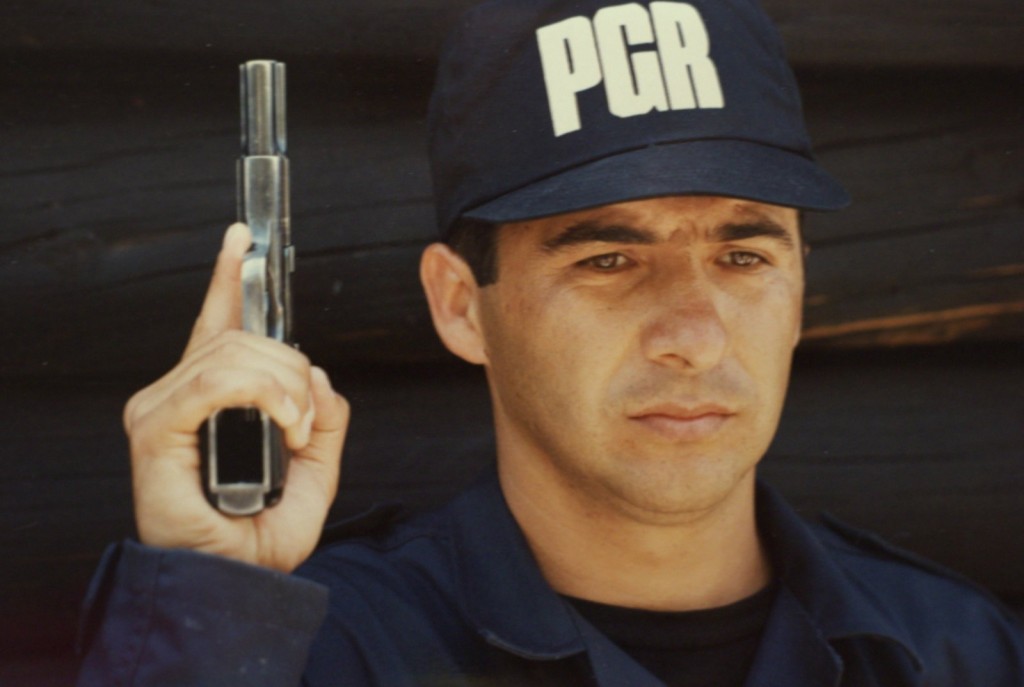

* Attorney general’s officials have formed elite anti-drug police units. They’ve stepped up cooperation with the army. They’ve helped write new laws to crack down on money laundering and allow U.S.-style prosecutions, complete with racketeering statutes.

* Officials have gone to the United States, Colombia, France, Italy and Spain to study organized-crime measures. They’ve written a law to allow phone tapping during investigations and to beef up protection for judges, prosecutors and witnesses.

* Authorities have begun raising police officers’ salaries and improving training standards. They’re firing drug agents caught accepting bribes. And they’re starting employee drug testing.

“This is just the beginning,” said Samuel Gonzalez Ruiz, a law professor who has assisted with the reforms. “We’re going from the top to the bottom. Things have to change.”

Longtime tolerance

One of the most important changes, some say, has to do with societal attitudes.

“Corruption has been around for a very long time. But today, it is less tolerable,” said Federico Estevez, a political scientist and former Zedillo adviser. “Today, it’s too costly for politicians to cover up and ignore corruption. In that sense, we don’t have the same system anymore. People have changed.”

Even so, most analysts expect that the cleanup will be a long process. Changing attitudes isn’t easy.

Corruption at the attorney general’s office has been so severe that some observers have suggested that Mr. Lozano fire everyone and start over.

Mr. Lozano isn’t ready for that, but he has opened criminal cases against 132 employees and fired, suspended or disciplined more than 300 agents. Among those charged: A Sinaloa state police supervisor accused of accepting an $8 million bribe for each cocaine shipment going through his district.

Mr. Lozano has also begun setting up a computer database to track employees. When he took over in December, there were no personnel files on 4,300 federal police agents, and he couldn’t locate 1,000 employees who were on the payroll.

While he pushes ahead with reforms, crime rates are soaring. An average of 523 crimes are reported per day in Mexico City, highest in the city’s history. Eight in 10 suspects are never caught. Violence is increasingly common. Assailants armed with machine guns often raid businesses and banks, killing anyone who gets in their way.

“Criminals have gotten so powerful that they don’t even pay attention to the police,” said Pedro Penaloza, a former Mexico City assembly member. “This is dangerous.”

A June 1995 poll in Mexico City’s Reforma newspaper showed that 90 percent of those surveyed worried they’d be victims of a crime – and 73 percent said they didn’t think the police would be of any help.

Some members of the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, are fed up and want Mr. Lozano to quit. They say they’re especially upset about the slow pace of the government’s investigation into the March 23, 1994, assassination of Luis Donaldo Colosio,the PRI’s presidential candidate.

They march to the attorney general’s office on the 23rd of each month chanting, “Justice! Justice!” Mr. Lozano has failed to keep his promise to solve the crime, they say.

“He should step down,” said Juan Jose Castillo, a PRI deputy.

Some analysts say the PRI only wants to discredit Mr. Lozano because he’s a member of the political opposition. They can’t help but notice that the crusading attorney general, nicknamed “Mexico’s Elliot Ness,” has higher approval ratings than the president in recent polls published in Reforma.

Swimming upstream

Despite his popularity, Mr. Lozano faces difficult odds. And history is not on his side.

Corruption has plagued Mexico for more than four centuries. Under the Spaniards, aspiring government workers, judges and provincial governors bought their way into office, then routinely bilked the royal treasury and took bribes.

In the many years since then, the stakes have escalated to a staggering degree, thanks in a big part to the drug trade and the insatiable U.S. appetite for cocaine, marijuana, heroin and other narcotics.

Mexico is the transit point for as much as 80 percent of the South American cocaine entering the United States. Traffickers are so confident that they’re using commercial-size airliners to bring the drug north. At least eight planes carrying huge, multiton loads of Colombian cocaine have landed in Mexico unmolested since 1994, U.S. drug agents say.

“Drug trafficking in Mexico is run by men of business, graduates of the most prestigious universities of the world,” federal Deputy Ramon Sosamontes said after returning from Colombia, where Mexican lawmakers learned some of the latest anti-corruption strategies.

Mexican officials have asked for U.S. help, and the Americans say they’re impressed with the Mexicans’ commitment.

“They’re going after targets they wouldn’t have dared touch” last year, one official said. Mr. Lozano “is one of the better attorney generals I’ve seen.”

Still, some Mexicans fear that the latest flurry of reforms will be ignored like many others.

“Our laws are beautiful on paper but difficult to apply,” said Carlos Schon, head of a Mexico City law firm.

Politics and money often get in the way of justice, analysts say. Some cite the recent case of Fernando Yanez Munoz, or Comandante German, the alleged guerrilla leader arrested on weapons charges in October. Hundreds of his supporters protested following his arrest and suddenly the accused man was freed, despite the government’s anti-crime rhetoric.

“They arrested me for political reasons, and now they set me free for the same reasons,” Mr. Yanez said.

Others say the government’s half-hearted internal audits are another sign of lack of resolve.

The audits, targeting the Mexican Congress and other government bodies, have uncovered tens of millions of dollars in suspected embezzlement and other irregularities. But auditors have dared to look only at 1993 budgets. Critics say the government is afraid to dig into 1994 or 1995 because that might hit too close to the current administration.

“There is a desire for reform, but it’s kind of scary to go all the way,” said Lorenia Trueba Almada, a human rights worker who monitors judicial affairs.

Ex-officers protest

In Mexico City, a dozen former police officers got so upset about corruption that in December they set up a protest camp along Reforma Avenue, a main thoroughfare. For the next 10 months, just about everyone who passed by ignored them.

Frustrated, one of the protesters, Ricardo Chaires, let his partners tie him to a wooden cross that was roped to an aluminum pole. “Say No to Police Corruption!” a nearby sign proclaimed.

City maintenance workers managed to get Mr. Chaires off the cross after six hours. Undeterred, he returned weeks later with a giant plastic bag and got inside. He called it his “happy world,” his way of saying that people are living in a dream land if they don’t take corruption seriously. That ended after unidentified men ran by and tore up the bag.

In Tijuana, human rights worker Victor Clark knows just how frustrating it is trying to change the system. For eight years, he’s denounced police torture of suspects, documenting about 400 cases. Only now, for the first time in Tijuana, has anyone been charged criminally, he said. In that case, the officers are charged with torturing five people falsely accused of stealing car parts.

“So many years had to pass before a police officer was charged,” he said.

Many observers believe that there won’t be any profound change until there is political reform. The same political party, the PRI, has ruled Mexico for 66 years.

“One of the first steps they should take is to give complete and undisputable autonomy to judicial agencies,” said Francisco Javier Pizarro, a former guerrilla who spent two years in prison in the 1970s.

Sometimes forgotten in these discussions about reform is that corruption can lead to great suffering.

In Tijuana, Lidia Moreno, 37, says police ignored her when she reported her son kidnapped. She and her husband were forced to sell the family store and pay a $20,000 ransom. But Miguel Angel, 16, turned up dead last year, his body unceremoniously dumped in a septic tank.

Human rights workers suspect that police were involved. And Ms. Moreno said she’ll never trust the law again.

“Some police are good, but they are few,” she said. “Most people who take government jobs don’t want to help people. They’re selfish. They only think of themselves.”

And in Manzanillo, after dozens of people were killed last month when an earthquake toppled the Costa Real hotel, the victims’ relatives complained that the hotel had been damaged in an earlier quake and should have never reopened.

Carlos Jimenez, whose wife was among those killed, blames the authorities, who deny wrongdoing.

“I know nature is ultimately responsible for the destruction of this hotel,” he said. “But the hotel owners could have done more. I live in a country where corruption is put above people’s lives, where justice has a meaning only in textbooks. In all my life, I have never seen justice done.”

Alejandro Paez, a free-lance journalist based in Mexico City, contributed to this report.