I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on April 9, 1995.

MEXICO CITY – A billionaire media mogul, a former president’s son and dozens of other Mexican VIPs have been granted the privilege of flying into the United States without customs inspections at the border, government documents show.

The U.S. Customs Service has allowed the practice since at least October 1993 even though two of the Gulfstream jets making the flights have been marked for special attention by the Drug Enforcement Administration and other agencies, internal customs documents show. Mike Horner, a former customs inspector in San Diego, has asked the agency’s internal affairs department to investigate. He says he believes that such flights may aid traffickers.

“They can fly all the way to Canada, and they don’t have to report for inspection,” he said. “Even astronauts who’ve been in outer space have to report to customs when they come back. What’s going on here?”

Mr. Horner and some other former inspectors contend that northbound travelers shouldn’t be allowed to skip inspections at the border because they say that’s where law enforcement agencies concentrate their anti-smuggling efforts.

Customs officials dispute that, saying the agency is equipped to fight smuggling at all entry points, not just the border.

Greg Doss, a customs spokesman in Los Angeles, added that travelers skipping inspection at the border are required to report to customs once they land at some point inland. So it’s not as if the travelers aid the drug trade, he said.

Customs officials say the flights into the U.S. interior – dubbed “overflights” in customs jargon – are aimed at making trips to the United States more convenient for corporations and individuals.

U.S. Rep. Brian Bilbray, R-Calif., said he worries that the overflight privilege may be abused by some.

“We may have to do a reality check here,” he said. “There’s such a huge potential for problems, for corruption. We’ve really got to be careful we don’t sacrifice the security of the country just to expedite trade.”

Any corporate executive or individual – and not just those of Mexican nationality – can apply to the U.S. Customs Service for overflight privileges. Documents obtained by The Dallas Morning News detail the overflight privileges of one company, Televisa, a giant Mexican television network.

Any corporate executive or individual – and not just those of Mexican nationality – can apply to the U.S. Customs Service for overflight privileges. Documents obtained by The Dallas Morning News detail the overflight privileges of one company, Televisa, a giant Mexican television network.

Televisa is the parent company of Jets Ejecutivos, an aviation firm in Toluca, Mexico. An Oct. 2, 1993, memo – signed by John Heinrich, the customs chief in Los Angeles – approved overflights for 14 Jets Ejecutivos pilots and 167 passengers for a period of one year.

Among the passengers is Emilio Azcarraga, one of Mexico’s richest men, with a fortune estimated at about $3 billion.

Mr. Azcarraga, the head of Televisa, is accustomed to exercising vast influence in Mexico. Forbes magazine in February 1995 ranked him as the second-richest man in Mexico behind Carlos Slim, a financier who owns a huge chunk of Telefonos de Mexico, the phone company.

Mr. Azcarraga – nicknamed The Tiger – was out of town last week, and his secretary said he would have no comment.

Customs documents show that four Jets Ejecutivos planes have been approved at one time or another for overflights into the United States.

Jorge Alva Hernandez, identified in the October 1993 memo as the firm’s director of operations, vehemently denied that any of the jets have drug ties.

“We’re a profitable company,” he said. “We’re not smuggling anything. We’re more than happy to comply with all the customs regulations because we have nothing to hide.”

The customs documents obtained by The News do not implicate anyone in drug trafficking. The documents merely show that two of the four Jets Ejecutivos plans have been identified as suspicious by the El Paso Intelligence and Information Center, which is run jointly by the DEA, the FBI and other agencies.

When the registration numbers on the tail of a suspicious aircraft are entered into Customs Service computers, an alert is triggered, advising inspectors to search the plane because it might be associated with drug trafficking.

There are many reasons for an alert, customs inspectors say. Here are a few: The plane’s pilot may have prior drug arrests. The pilot may have been spotted associating with suspected

traffickers. Agents may have at one time found traces of narcotics in the plane. Or, the plane may be regarded as suspicious simply because it makes frequent trips to Bogota, Colombia.

Mr. Alva Hernandez said he believes that the alerts were placed in the computer system because one of his pilots was questioned by the Customs Service about some contraband tequila years before joining Jets Ejecutivos. Mr. Alva Hernandez said the pilot was an innocent victim in that case, had no idea there was tequila aboard his plane and later had his name cleared.

Wayne Pinkstaff, agent in charge of investigations for customs in Los Angeles, said he couldn’t discuss the status of the Jets Ejecutivos aircraft because of privacy laws.

Speaking generally, he said a mere computer alert doesn’t necessarily ruin someone’s chances of getting overflight

privileges. But if the agency suspects anyone is tied to

trafficking, their privileges would be revoked, he said.

A U.S. drug agent, speaking anonymously, said he doubted that an illegal liquor shipment would lead to a computer alert.

“I wish tequila was the only thing we had to worry about,” he said.

The Jets Ejecutivos passengers include some of Mexico’s wealthiest and most notable figures. Among them: Eduardo Echeverria Alvarez, brother of former President Luis Echeverria; Miguel Aleman Velasco, son of former President Miguel Aleman; and Romulo O’Farrill Jr., co-owner of the Novedades newspaper.

Most of the others on the list are relatives of the O’Farrill, Aleman and Azcarraga families, including everyone from young children to grandparents. Spokesmen for the O’Farrill and Echeverria families, as well as for Televisa and Novedades, did not return phone calls.  Representatives of the Aleman family couldn’t be reached for comment.

Representatives of the Aleman family couldn’t be reached for comment.

The four Jets Ejecutivos planes are allowed to land in Dallas; Las Vegas; Los Angeles; New Orleans; Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; Vail and Aspen, Colo.; and several other cities without stopping at the border.

Mr. Alva Hernandez said he’s grateful for the overflight privilege because it saves his company time and money.

“We fly everywhere,” he said. “If we landed at the border, this would cause a little inconvenience to the passengers on board. This is a corporate service. You have VIPs on board, and you try to give them the best service you can.”

Some customs inspectors say that customs officials don’t hesitate to grant such privileges to those with wealth and political connections.

“Customs laws are being applied selectively,” said a supervisory customs inspector who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “It’s wrong. I really feel every person should be treated equally. That’s the way you should do business.”

Some private pilots dispute that, saying the exemption isn’t difficult to obtain.

“It’s fairly easy. It’s an administrative process,” said Brian Burke, a Texas pilot. “I don’t get a sense that there’s

favoritism.”

Mr. Burke also disagreed with the idea that smugglers would try to take advantage of overflight privileges.

“The risk outweighs the gain,” he said. “You’re announcing to everybody, `I’m going from Point A to Point B and here’s where I’m going to land.’ If I’m smuggling drugs, I’m not going to tell you I’m coming. People who smuggle drugs don’t give two hours’ notice.”

The threat of a thorough customs inspection in the United States is another factor that might persuade a trafficker to avoid making an overflight, he said.

“I’ve had the airplane gone over with a fine-tooth comb in Cleveland,” he said. “I don’t think it’s fair to say the

inspections are any less vigorous inland.”

Those opposed to overflight privileges say they believe the Customs Service isn’t doing enough to monitor flights into the United States.

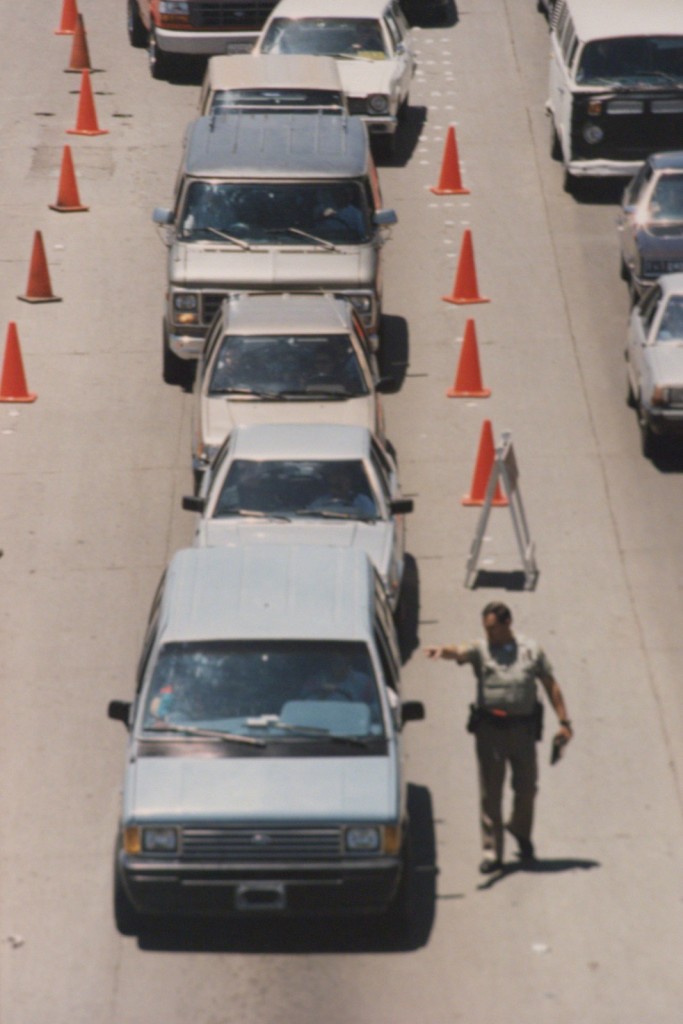

Under customs regulations, private pilots flying in from Mexico and other southern points must land at the border for inspection before proceeding north. Failing to do so can bring a fine of up to $5,000 and the seizure of the aircraft.

The law specifically exempts pilots carrying passengers who are seeking medical treatment in the United States. Beyond that, the regulations offer few guidelines, saying only that customs officials may allow these flights at their discretion.

Mr. Horner said that as early as March 1994 he began telling the agency’s internal affairs investigators that he believed the overflight system was being abused. But he said the flights have continued, a claim that is supported by customs documents.

Mr. Horner and some other current and former inspectors say that overflights should be allowed only when there’s a crisis situation.

Bad weather may prevent a plane from landing at the border, they say. An air ambulance carrying a critically injured accident victim may be in a desperate rush to get to an inland hospital. Or a pilot escorting government dignitaries may not want to land at the border because of security concerns.

Customs officials who grant overflight privileges have taken a broader interpretation of the law and say they are doing nothing wrong.

Still, to eliminate any chance of trouble, the agency screens those given overflight privileges, doing background checks on all passengers and crew, said Arthur Gainer, chief customs inspector at Los Angeles International Airport.

Customs officials then pass that information along to

colleagues in other states, said Tom Winkowski, district director of customs in Los Angeles.

As an additional anti-smuggling measure, customs warns those who make overflights to be on the alert for suspicious activity.

Internal customs memos tell people to watch for planes:

“Carrying numerous cardboard boxes, duffel bags, plastic bags . . . seeds, green vegetable matter . . . cellophane paper indicating possible marijuana debris. . . . Strong odors from the aircraft (perfumes and deodorizers are often used to disguise the odor of marijuana and cocaine). . . . Payment of cash for fuel or services or display of large amounts of cash. . . . Pilots who own or operate expensive aircraft with no visible means of support . . .”