I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Aug. 17, 2000.

CHICHICASTENANGO, Guatemala _ Isabela Mejia knelt on a church floor sprinkled with red and white rose petals and opened little brown paper bags.

“Right foot,” one bag read. “Left collarbone.” Isabela emptied the bags onto a white sheet, shaking each one to make sure even the dust came out. After almost two decades of not knowing, the 50-year-old Mayan widow had finally found her husband.

Some of his bones, at least.

The killing fields of Guatemala’s central highlands are full of bones, buried but not forgotten beneath the rich, dark soil. And now people are digging them up, mourning their loved ones at last in churches and cemeteries.

They’re uncovering secrets, too, hidden away in the bones all these years.

Secrets of a war that left as many as 200,000 dead or missing, the worst massacre of highland Indians since the Spanish Conquest of the 1500s.

Secrets of children slammed against trees, of women raped, of men burned alive. Shameful secrets of a war fought quietly, brutally, at times with the help of Washington and the CIA.

Hidden wars rage around the world, in Africa, Asia and other spots. People fight over power, religion, social justice. Then it happens quite unexpectedly: The killing stops. The appetite for blood goes away. One side wins, one side loses. Or someone intervenes.

But that’s rarely the end of it, not in war. Because peace is bittersweet.

Peace is a battle. Guatemala knows.

Four years after the war’s end, the country of 12 million remains fiercely divided between rich and poor. What hurts most, many Guatemalans say, is that 36 years of dying accomplished so little _ stacks of neatly typed peace accords, for sure. But that’s just paper.

The Mayan rebels who fought the military are still miserable, treated like second-class citizens. Infant mortality and illiteracy rates remain among the Western Hemisphere’s worst. Eighty-seven percent of the people are poor, and 2 percent of the population owns almost 70 percent of the fertile land.

Granted, the fighting is over. Extrajudicial executions are no longer routine and ex-rebels have a political party. But there’s little sense of justice, many Guatemalans say.

An estimated 80,000 widows and 250,000 orphans scratch to survive while wartime officials accused of exterminating unarmed civilians enjoy only slightly diminished status. One notorious former general even serves as president of the Guatemalan Congress.

New questions

Grave new problems, meanwhile, have emerged.

“The economy is bad, the political situation bad, social problems are worse every day,” said Julio Balconi, 53, a former defense minister and head of the National Alliance for Peace, a war-reconciliation project.

“How can we envision another Guatemala if these problems aren’t solved?”

Sadly, many of his countrymen say, stitching the nation back together could take longer than the war itself.

“We wonder if it was all worth it,” said Pedro Brito, a Mayan activist in the town of Nebaj, one of the hardest-hit. “People are still poor and the government acts like nothing happened, like we’re dogs.”

The war was one of the bloodiest the Americas has ever seen. Soldiers razed 440 villages, by their estimate, burning cornfields, sacred to the Mayans, and killing anyone or anything. Dogs, chickens, cattle. Children, too _ to wipe out the seed.

An estimated 1 million Guatemalans abandoned their homes to escape the insanity, “a maniacal windstorm,” one priest called it.

The worst year was 1982, when about 75,000 people were killed. Survivors told of soldiers hacking off enemies’ legs so they’d fit into shallow graves where they were burned alive.

Many peasants were angered by such stories and joined the uprising, and by the mid-1980s the guerrillas had as many as a half-million supporters.

Bullets and frayed nerves

Jorge Toj was 7 when he heard talk of rebellion. Some men came to his village and explained that the rich ate more tortillas than the poor. Even a child could understand that wasn’t fair.

So by age 8, he was a guerrilla lookout. He and his friends would play soccer or marbles. “And when soldiers came, we’d run, whistle and let everyone know.” Soon soldiers started dropping off ominous messages at his house.

“Communists,” they said. “You’re going to die.” On Mother’s Day in 1980, his uncle Baltazar Toj was murdered.

“I was walking to school when I saw the body,” said Jorge, 28. “He was tied up and his eyes were cut out. He had no tongue and no ears. I saw that and really started to hate the army. I was 10.”

Soon after, Jorge, his 11-year-old brother and their mother fled town and joined the rebels.

Jorge said he was in his first firefight at age 14 or 15.

“It was difficult, feeling the heat of the weapons, the bullets. You’re scared, nervous. You get chills. You don’t know if you’re going to live or die. But then I’d remember my uncle Baltazar, his body with no eyes, and I’d fight.”

Hector Lopez Bonilla fought, too, but for the army. He was a Kaibil, a special-forces commando.

Kaibils have an almost mythical status in Guatemala. One ex-commando said he was forced to hunt down and eat wild game.

“Did we cook it? No! It was arrruuungh!” he said, mimicking the sound of someone biting into and tearing off flesh. Other commandos drank dog blood.

Lopez, now a political consultant, said what he liked was Kaibil discipline. “Even a dirty fingernail could get you an hour’s detention,” he said.

During the war, he headed Operation Xibalba, named after the Mayan equivalent of hell. The operation infiltrated a 28-rebel unit of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor. All were eventually captured and killed after interrogation, according to the 1999 book The Guatemalan Military Project.

“I saw soldiers die, guerrillas die,” said Lopez, who was nearly killed himself when a mine fragment ripped into his chest.

“The pacifists, the utopians would like war to be abolished,” he added. “And I wish it would be, that man could reach the highest level of the cosmos and understand the value of life. But the reality is that in each minute that goes by, a conflict breaks out somewhere that could lead to an intense, armed battle.

“Once the bullets are fired, reason ends.”

Guatemala’s Catholic archdiocese said soldiers mutilated pregnant women, cut off men’s genitals and sexually assaulted girls. One victim said 70 men raped her.

Former government officials dispute such claims.

“I can’t believe that while people are killing each other, someone’s going to be raping a woman … ripping the fetus out of a pregnant woman,” former Defense Minister Hector Gramajo said. “It’s not humanly possible, even if it’s a monster doing it.”

What lifted the death toll, he said, was that rebels recruited civilians, a guerrilla technique called “popular war,” once used in China and Vietnam.

“The rebels’ tactics killed a lot of people. They sent masses of unarmed people against the army,” Gramajo said.

The military adopted similar tactics, recruiting about 1.3 million Indians _ 17 percent of the eligible males _ into its pro-government civil patrols by 1984, researchers say.

That made the war “much more bloody,” said Gramajo, who is credited with curbing some of the worst military abuses of civilians while he was defense minister from 1987 to 1990.

Still, some bloodshed was unavoidable, he said.

“War is violent by nature. They propose violence. We have two options: Annihilate the enemy with bullets or take away their will to fight. We took away their will to fight,” he said.

The two sides reached peace in 1996 after 10 years of talks. The challenge now is moving ahead. The war was so devastating and costly “it put our future in hock,” one former official said.

Indeed, the country brims with walking wounded: people who suffer panic attacks, nightmares and what Mayans call el susto, the fright, their version of post-traumatic stress.

Torture

Eighty-three percent of the war dead were Mayans.

Tomas Mendez, 35, survived _ barely. Assailants snatched him in April 1985 and dragged him to a church that soldiers had occupied.

“They gave me electric shocks and kicked me,” he said. “‘Who’s the rebel boss?’ they’d ask.” Soldiers finally freed him after breaking his back. Today, the Mayan gets by selling watches.

Emilia Garcia, a 72-year-old grandmother, suffered another kind of agony. In February 1984, intelligence agents clad in blue kidnapped and presumably killed her son Edgar, a student leader.

“He didn’t deserve whatever happened to him,” said his mother, now leader of a group for relatives of about 45,000 people who disappeared. “I’m sure he was tortured horribly.”

‘The goodness of humans’

Thousands of maimed bodies are buried in the countryside.

“Bosnia has land mines. Guatemala is mined with graves,” said Fredy Peccerrili, director of Guatemala’s Foundation of Forensic Anthropology. He and his 44-member team gather evidence for war-crimes cases and have dug up more than 60 graves since 1995.

He held up a skull and pointed to a pea-sized hole. “This person was hit by a metal fragment, most likely from a grenade. Bones tell us stories. All we do is translate what they say.”

It’s a gruesome job, digging up the remains of girls sliced up with machetes, of women mutilated.

But the 29-year-old said, “I still believe in the goodness of humans. It’s made me a better person to feel other people’s pain, to discover my own country’s past.”

Many Indians are terrified to search for buried relatives because of fears the killing will start again. But some brave souls come forward. And when their loved ones’ remains are found, they release years of pent-up emotions.

They cry and pray. They light candles and help retrieve bones.

Nobel laureate and Mayan activist Rigoberta Menchu says Guatemalan officials wanted to wipe out the Indians. She demands they be jailed on genocide charges.

Former Gen. Efrain Rios Montt, the country’s military leader from 1982 to 1983 and now president of the Guatemalan Congress, denies there were any “ethnic killings.” “That was not state policy,” he said.

‘I’m not crazy’

Ex-officials say the genocide claims are part of a revenge campaign led by human rights groups, the Catholic Church and others.

“These accusations are totally false,” said former Gen. Benedicto Lucas Garcia, a former army chief of staff.

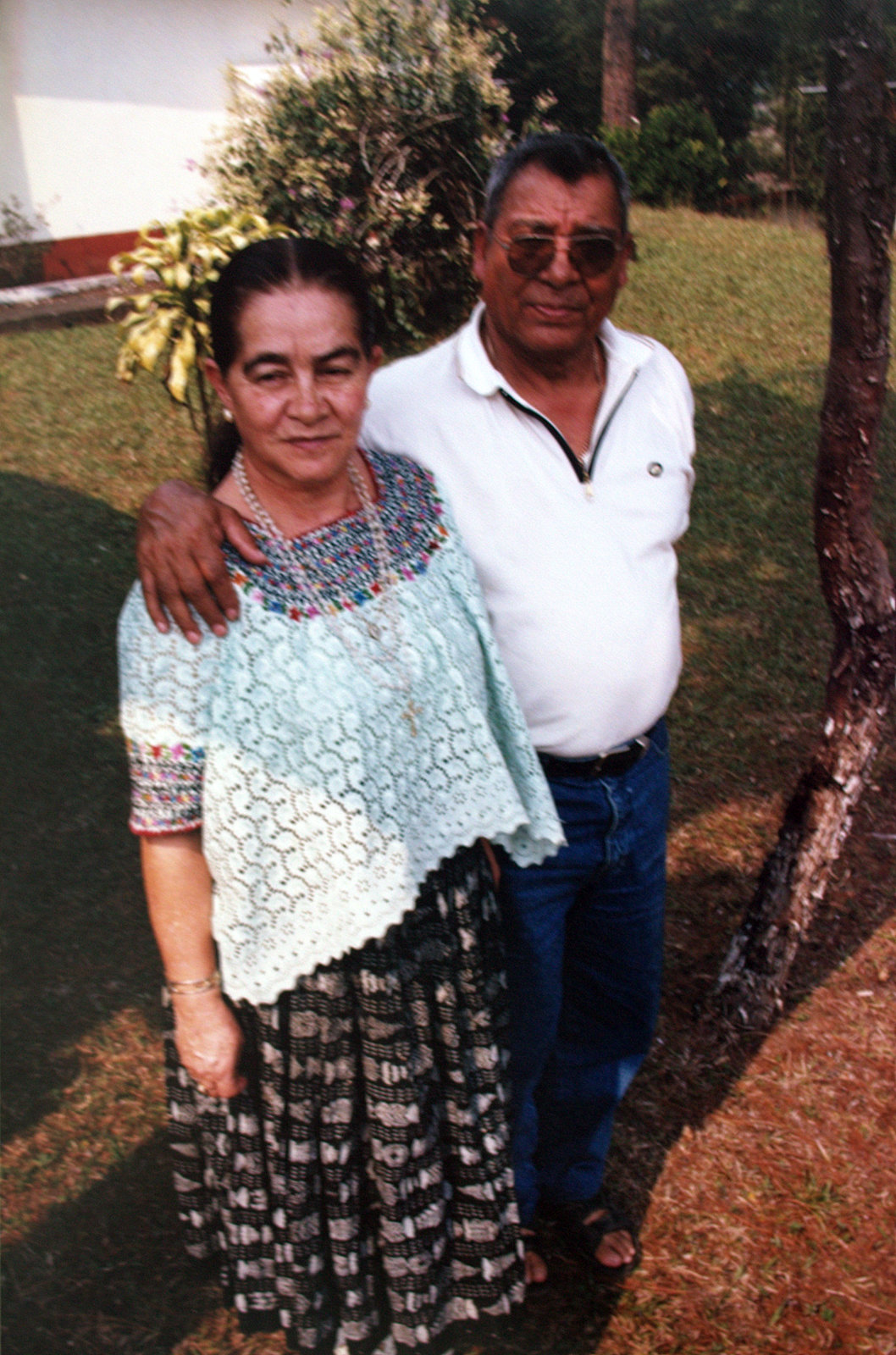

Retired since 1982, he lives on a ranch in the town of Coban. He grew up barefoot and poor. He speaks Kekchi, a Mayan Indian language. His wife, Maria Elena, is half Mayan. So, the ex-general asks, how could he be a ruthless Indian killer?

Retired since 1982, he lives on a ranch in the town of Coban. He grew up barefoot and poor. He speaks Kekchi, a Mayan Indian language. His wife, Maria Elena, is half Mayan. So, the ex-general asks, how could he be a ruthless Indian killer?

“We’re painted as savages,” he said. “Not true. If I killed, and God forgive me, I did it in battle. But kidnapping and murdering people, that’s the stuff of psychopaths, crazies. And I’m not crazy.”

The ex-general spoke from a couch in his living room. Black-and-white pictures, diplomas and certificates lined the walls.

“I’ve done a lot of good,” said the ex-general, a former martial-arts black belt who is fit at 67.

Asked to describe his philosophy of war, he recalled telling his troops, “If we’re ambushed, we’re going to fight back. None of this, ‘Hit the dirt!’ If you’re going to face the enemy, well, man, you’re going to do it like a man and a soldier, not a coward.”

His 76-year-old brother, Romeo Lucas Garcia, was president from 1978 to 1982. Former rebels blame him for some of the worst wartime atrocities. He once called his anti-insurgency campaign an “allergy” that people had to “learn to live with.” Now in Venezuela, he is accused of genocide, but Benedicto Lucas said his brother is so ill with Alzheimer’s disease that he knows nothing about it.

“I saw him 10 years ago. He said, ‘Who are you?’ ”

Military control

Just how far the war-crimes cases will go is unclear.

Guatemala’s “judicial system is extremely weak and nearly nonfunctional,” according to a January report by the Washington Office on Latin America, a nonprofit research group.

“Widespread incompetence and corruption” are among its shortcomings. “Thousands of serious crimes go unpunished.”

Cases against military officers are particularly hard to prosecute. The officers have run Guatemala for much of its modern history. They have political clout, autonomy and money, too, operating everything from parking garages to fish farms.

“They pretty much control the country,” said Helen Mack, a Guatemalan human rights activist who spends much of her time digging into the military’s secret affairs.

Certainly the armed forces were in charge during the war, and the mission was to kill. Quietly.

“The conflict was much more cruel, more perverse than any in Latin America, but few people knew it,” Mack said. “The army deliberately hid what was going on.”

Her sister, anthropologist Myrna Mack, was studying the war’s impact on Mayan Indians when a military agent assigned to the presidential guard fatally stabbed her 27 times in September 1990.

The agent was caught and jailed. Helen Mack said she tried to find out who ordered the killing and ran up against a virtual parallel government of elite military and presidential forces.

For her efforts, she won the Alternative Nobel Prize in 1992. She used the $60,000 in prize money to set up a research foundation aimed at government reform. But it has been an uphill fight. No officials have been punished for war crimes, she said.

Bartolo Fabian, 46, a highlands broccoli farmer, wants the rebels punished.

Guerrillas murdered his father and brother in January 1982. They also kidnapped his 14-year-old sister and forced her to join them. “They hurt us, they hurt our family,” he said.

Others fault the guerrillas for failing to protect their followers. Former rebel commander Rodrigo Asturias responds, “I never imagined that the army would come after us like it did, with such viciousness. The army’s reaction was completely out of proportion to the threat.”

It was revealed after the war that U.S. military and intelligence agencies helped keep the Guatemalan killing machine humming during much of the fighting.

U.S. aid

Today, it’s a different story.

The United States is spending $260 million over four years, more than any other foreign nation, to help Guatemala recover.

“I can look any Guatemalan in the eye and say that we are doing our part,” U.S. ambassador to Guatemala Prudence Bushnell said. “We’re here, we’re ready to help.” But only time heals some wounds, she said.

“It took us over 100 years to get over a horrible civil war. I don’t think we can expect other societies to do much better,” she said.

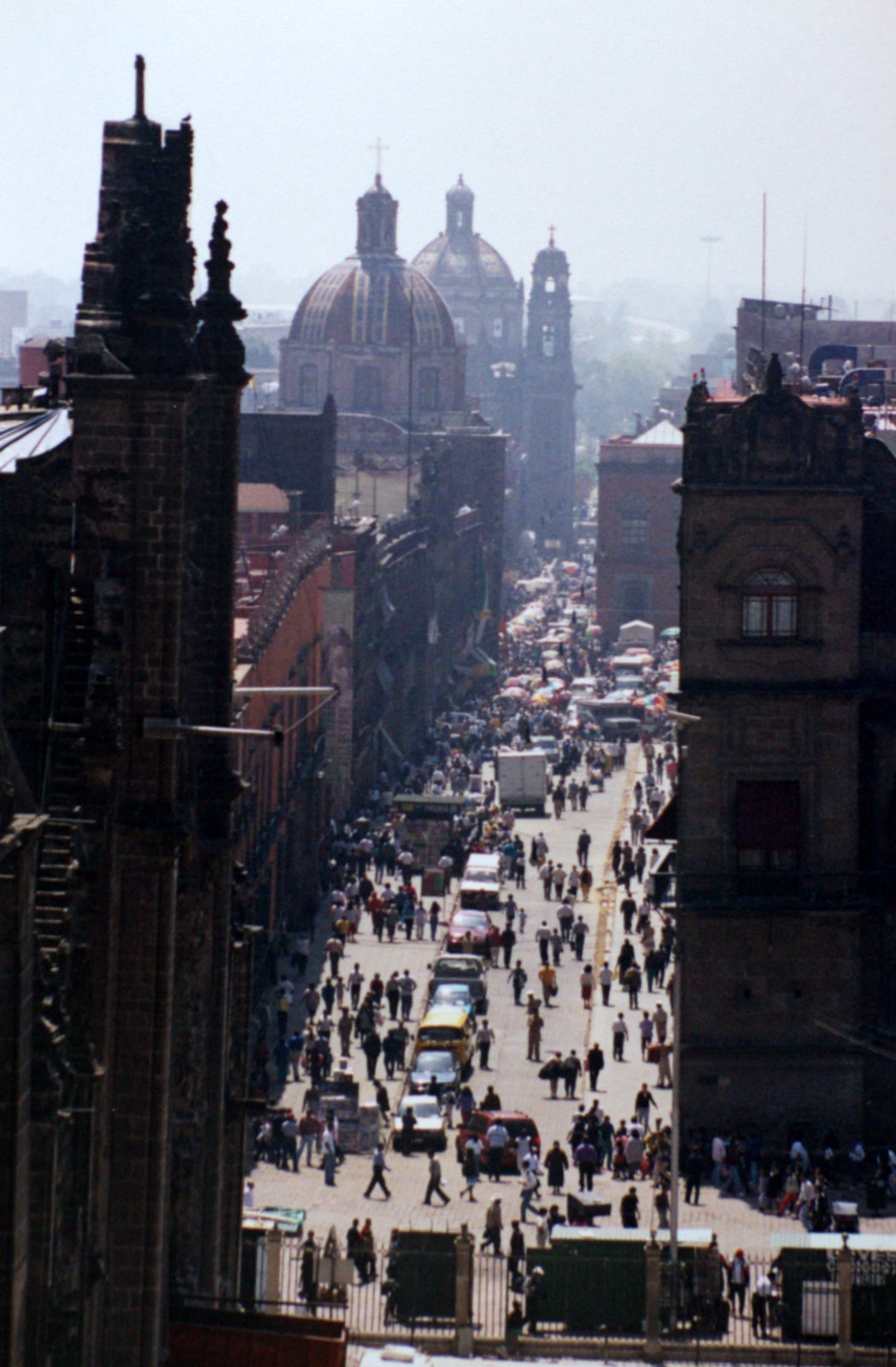

New problems make recovery all the more difficult. Guatemala City is now the third-most violent city in Latin America, and more than half the nation’s labor force is unemployed or underemployed.

Riots erupted in Guatemala City in April after bus fares went from 13 cents to 20 cents. Five people were killed in the unrest, the worst since the war’s end.

“What triggered the war _ poverty, discrimination, exploitation _ still exists,” said Vidal Marroquil, a student leader who staged a hunger strike during the riots.

The government has done little to help, some critics say, and instead stumbles around looking for scapegoats.

Innocent target

“It’s a political show,” former Col. Byron Lima Estrada said. He and his son, a former army captain, are in prison charged with killing a prominent bishop in 1998. Juan Jose Gerardi was found bludgeoned to death in his parish house garage two days after unveiling a scathing report blaming the army for war atrocities.

Byron Lima, 59, admits a dislike for Communists.

“Ultra-conservative,” the CIA calls him in a declassified report. “Bent on preserving the military’s grip on power. … Highly outspoken. … Enjoys an occasional Scotch (with a water chaser).”

Lima, 59, calls himself a convenient but innocent target. He said he retired from the army years ago and opened a little store to supplement his $241.76 monthly pension.

Lima, 59, calls himself a convenient but innocent target. He said he retired from the army years ago and opened a little store to supplement his $241.76 monthly pension.

“Why would I kill a bishop?” he asked.

Others are convinced he’s guilty. It’s a murky case.

What no one doubts is that the search for peace in Guatemala has been messy.

“We have had to work very hard to learn that peace isn’t the end of the fighting,” said Asturias, the former rebel leader. “Peace is the search for solutions to problems that caused the conflict.”

For too many years, secrets have held Guatemala back. Secrets of war. Secrets of power and money.

Some Guatemalans are hopeful, dreaming of the day when all the truth is known. Truth brings justice, they say.

Some Guatemalans are hopeful, dreaming of the day when all the truth is known. Truth brings justice, they say.

But Isabela Mejia, the Mayan widow, only wanted to unravel one little mystery: What became of her husband, Tomas, after he was killed in 1982? Was his spirit trapped underground? Was he scared and lonely? Were chuchos _ dogs _ eating his bones? Now, in a church in the highlands town of Chichicastenango, she waited with other Mayan widows as workers opened boxes of bones exhumed from hidden graves.

She spotted her husband’s shirt and battered straw hat. Then she saw his bones. She touched them gently and began putting them into a pine coffin.

“I’m happy he’s not buried like an animal,” she said.

Hurry up, someone interrupted. A funeral party was waiting. So Isabela held back the tears one more time, hastily gathered Tomas’ bones and carried them away.

Her reunion was over, rushing by like the musty incense wafting through the dimly lit church.