I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on June 25, 2001.

Heirs of a fabulously wealthy Spanish family say they are close to finding a long-lost inheritance worth billions of dollars.

Never mind the skeptics who say the centuries-old fortune is a myth. Thousands of would-be inheritors in Cuba, Florida, Texas and beyond burn with the fever. Gold fever.

And any day now, they are convinced, Cuban authorities will announce they’ve secured the loot and ask inheritors to step forward.

There’s just one hitch: Not a speck of gold, not a single shimmering jewel from the legendary Manso de Contreras fortune has been unearthed. Or if it has, no one’s talking about it.

Believers, including some Texas residents who play a central role in the quest, aren’t giving up.

“It’s not a fable,” said María Hernández, 52, a cancer prevention researcher in Houston. “It’s just that the money’s been hidden away for so many years.”

Centuries, in fact.

The trail of the so-called Manso Millions stretches back more than 400 years, beginning with a Spanish nobleman named Francisco Manso de Contreras.

Nobleman’s spoils

In 1598, King Philip of Spain sent the nobleman – his cousin – to the Caribbean to prosecute French and Dutch pirates and seize their stolen treasure. As was the custom, Mr. Manso de Contreras kept part of the booty and sent the rest to the Spanish crown.

Already a wealthy man, he became even richer, amassing great quantities of gold, precious jewels and land.

In 1603, he ventured into Cuba and became enchanted with the island, according to family lore. He and his brother, Antonio, settled in the colonial town of Remedios near the northern coast.

Their empire grew. No one disputes that. And from 1704 to 1804, Manso family descendants socked away at least $50 million in gold currencies and jewels. They put the money in British banks to hide it from the Spanish crown.

The deposits accrued interest and could be worth a staggering $3.7 trillion today, the hopeful say.

“This would make it the largest and richest inheritance in all of the Americas,” one Florida heir said. “A big chunk of change.”

Houston lawyer James Carmody sent the names of depositors and what may be their account numbers to the Bank of England.

A written reply came back: “There is no indication of anything which might possibly suggest the existence of any deposit.”

Undeterred, the lawyer is trying to force the British crown to open up its archives.

“It’s just a question of finding the smoking gun,” said Mr. Carmody, whose first client in the case was Ms. Hernández.

He now represents 3,231 potential inheritors and regularly adds new names to his computer database. The Cubans, he has learned, have managed to obtain a bootleg version of his list, evidently lifted from an e-mail he sent to a client.

Cuban officials declined to comment.

Many heirs are convinced that Cuba is hot on the money trail. And they pass around a grainy video recording in which a purported Communist Party leader says coyly, “There are things … I cannot talk about.”

Many heirs are convinced that Cuba is hot on the money trail. And they pass around a grainy video recording in which a purported Communist Party leader says coyly, “There are things … I cannot talk about.”

Mr. Carmody believes the Manso fortune may have been transferred to Her Majesty’s Treasury many years ago. Spokesmen for that office, which safeguards royal accounts, did not respond to a request for information.

Money trail

Historians say any number of things could have happened to money. The British crown could have seized it while Spain and England were at war. Or it could have been spent. Whatever happened, they say, it’s unlikely the fortune still exists.

“Completely wacky” is how one leading professor of Spanish history described the case.

“This is just a pie in the sky. All these poor people are hoping to have the goose that laid the golden egg wander into their barnyard,” said the professor, who asked not to be named for fear of getting nasty phone calls and hate mail from inheritors.

Indeed, the mere suggestion that the mother lode might not exist infuriates believers.

After a Cuban newspaper in February said the fortune was probably a fantasy, it was forced to print an apology. “At no moment was it our intent to kill your hopes,” it read.

Some inheritors already know how they would spend their share of the money.

“I’ll probably get a Ph.D. in history, do some charity work, quit my job and do a lot of traveling,” said Damarys Vazquez, 49, a Miami executive.

One Cuban exile reportedly tried to buy a house using her expected windfall as collateral.

Others journey to Cuba when the fever strikes.

Treasure quest

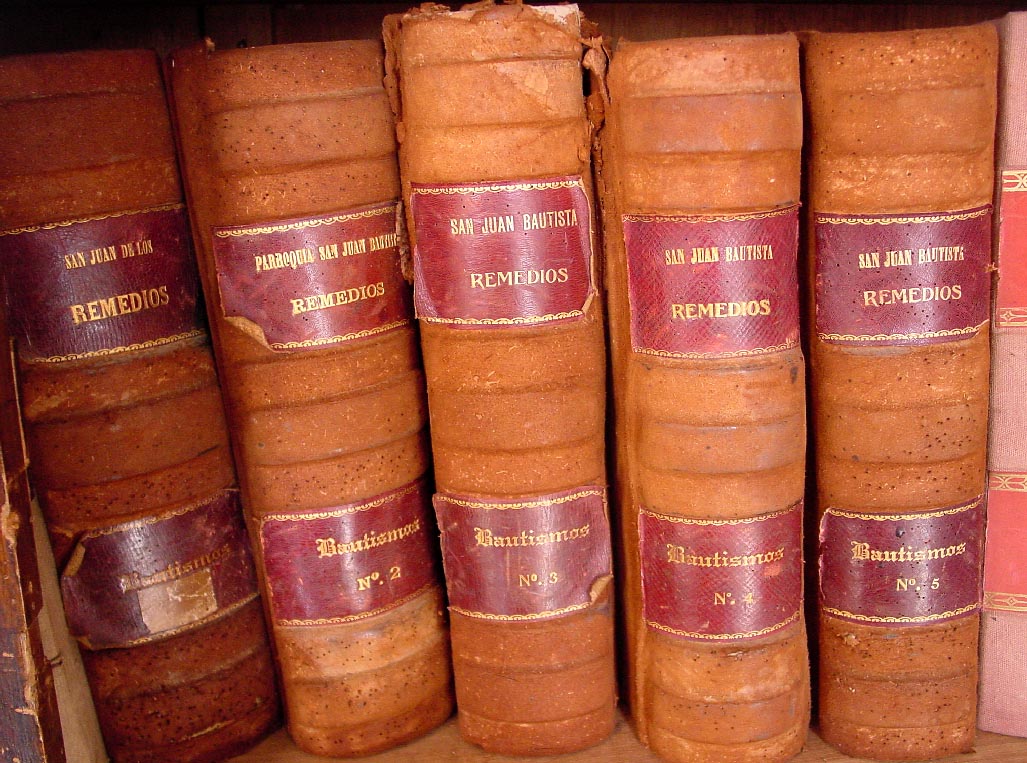

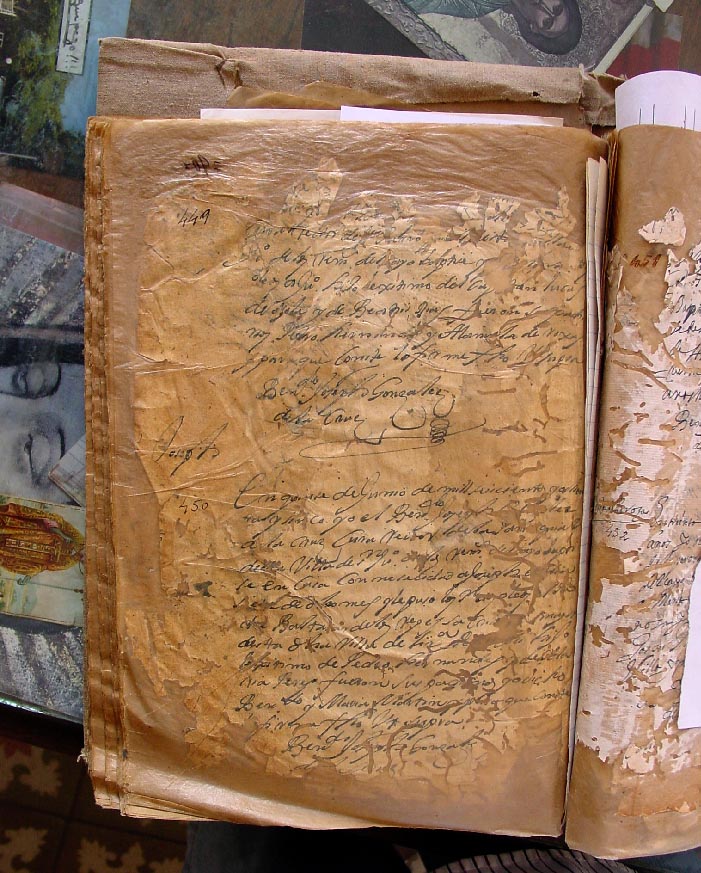

They go to the sleepy town of Remedios and knock on the back door of a 451-year-old church. Inside are the coveted marriage and birth records that trace the Manso bloodline.

“People come from all over to look at these,” said Adelaida Leopo, turning the pages of a worm-eaten volume containing documents 355 years old. “They live with the dream that they’ll be rich someday.”

The 62-year-old has been keeper of the parish archives for more than a decade. For five Cuban pesos (22 cents), she will search the records as customers wait. And for 10 pesos, she’ll bang out a copy of a record on her 1940s-era Remington typewriter.

Some people offer her bribes, she said, to falsify the certificates, but she declines.

“I’m not going to say that I don’t need the money,” she said. “But money doesn’t last. Love does. And the love you can feel is worth more than any sum of money.”

Others, though, would rather have the dough. And in Internet forums dedicated to the family fortune, Manso clan members spend hours plotting ways to get to the money.

They also spend a lot of time insulting one another. They call one another communists and ridicule their foes’ intimate body parts.

Said one family member: “We act like enemies when we should be helping each other. Don’t forget that at one point in time we were close cousins.”

Relatives clash over whether the descendants of slaves should get any money. It was common in the 1600s and 1700s for masters to let servants carry their surname even though they didn’t share the same bloodline.

Others want to limit the number of generations that qualify.

As it is, no one knows how many heirs there are. Estimates range from 6,000 to nearly 60,000.

Another unknown is the payout. At least $10 million apiece, some family members say.

Rumor mill

Rumors abound.

Inheritors say the British and Cuban governments, along with the Vatican, will get a share of the loot as part of secret negotiations that they say are ongoing.

The Cuban government, so the story goes, won’t hand out the money in lump sums. Recipients will get several thousand dollars up front and $350 per month for life.

They’ll also have the right to buy a house and a car, and the banks will issue them yellow debit cards, said would-be heir María Hernández in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., not to be confused with the Houston woman by the same name.

Ms. Hernández, a marketing manager, helped start the Commission of Inheritors Abroad, one of several organizations working to find the family fortune.

Ms. Hernández, a marketing manager, helped start the Commission of Inheritors Abroad, one of several organizations working to find the family fortune.

“We believe that Cuba already has some funds in its banks and is awaiting other bank transactions from England,” she said. “The Cuban government initiated this investigation on behalf of the inheritors in Cuba and has obviously been successful.”

The thought that the authorities are close to passing out the cash has many people in a panic.

“Here in Miami, things are really in chaos,” Ms. Vazquez said. “We don’t know what to believe anymore.”

“Don’t believe a word anybody tells you,” one man advised in an Internet forum. “One day you hear about platinum credit cards, the next day they are giving out Blockbuster Video gift certificates. Everybody needs to just forget about it. Keep working at your jobs and stop calling nonprofit organizations and promising to make huge donations. You don’t have the money!”

Esteban Granda, 79, president of the Remedios parish council, doesn’t believe in the tales of the Manso Millions. Unscrupulous law firms in the 1940s created a ruckus over the supposed fortune to drum up business, he said.

“They’d put ads in the papers saying that the bank in London was looking for inheritors,” he recalled. “It wasn’t true, but the newspapers would print anything if you paid them. I wouldn’t move a finger for that money.”

Still, many people are obsessed.

“They’re desperate. They say, ‘When are we going to get paid? When?’ I’m in line to get money, too, but I don’t torment myself with it,” said Iris Morales, a 57-year-old Havana seamstress. “It’s a thing of destiny.”

Practically all of Cuba dreams of the money, said Carmen Lemos, a Havana lawyer who investigated whether the fortune exists.

“But I think the inheritance is in people’s minds and not in any bank.”