I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on July 6, 1998.

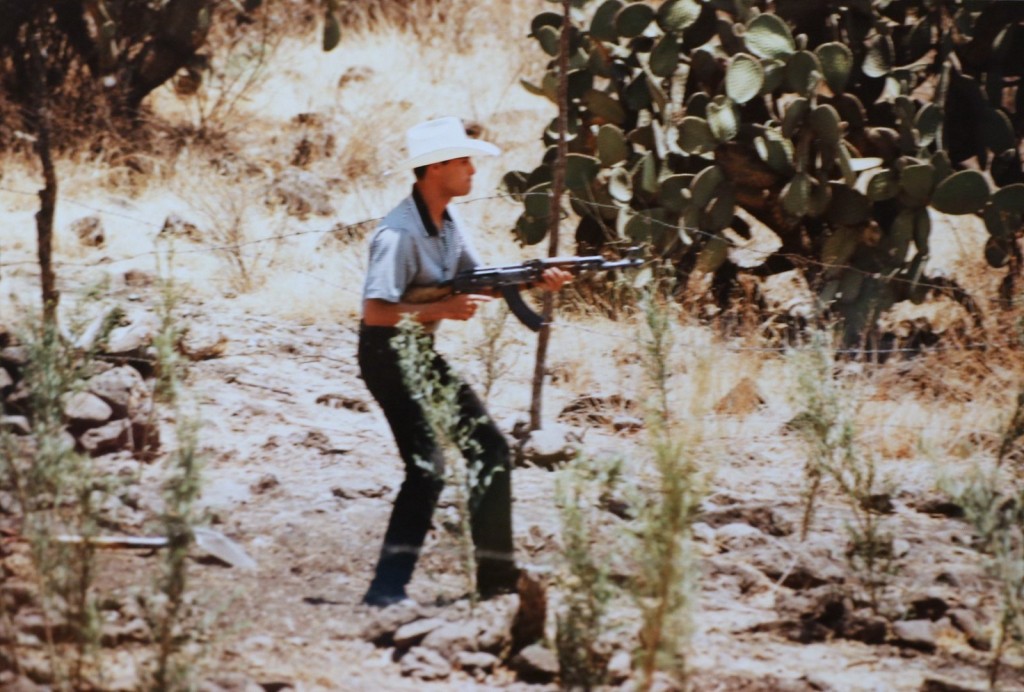

Reputed gangsters with names such as Cheese Face and Scorpion saunter along the same streets as factory workers and plant managers in this bustling yet troubled border town. San Luis, sprinkled with opulent mansions and wobbly cardboard shacks, is a place of good tidings and bad, of prosperity and plentiful jobs, of gangland hits and tragic deaths.

Amid the silence and fear, Mexicans in San Luis and many other communities along the U.S.-Mexico border are struggling to adjust to harsh new realities. The border economy is booming as the North American Free Trade Agreement approaches its five-year anniversary. But business also is good for the crooks, hitmen and drug traffickers.

As the millennium nears, leaders of this wind-swept town south of Yuma, Ariz., face tough choices. They can stand up to the local drug barons and try to turn San Luis into a free-trade haven. Or they can surrender to organized crime’s corrupting powers. Or they can do a little of both.

“Life is more difficult and complicated than ever,” said Petra Santos, a leader of the left-leaning Party of the Democratic Revolution in San Luis. “Corruption’s a problem, but you can’t go around saying some guy’s a criminal. That will cost you your life. So people keep quiet.”

Crime is rising despite an unprecedented police and military buildup. Traffickers are shelling out millions of dollars to buy off local politicians, U.S. drug agents say. And they’re also snapping up legitimate companies to shield their sprawling smuggling operations, according to a recent report by Operation Alliance, a task force of experts from the U.S. Customs Bureau and other agencies.

According to the confidential report: “Opportunities for traffickers are significantly greater with NAFTA.”

Before long, some U.S. agents fear, legitimate businesses will become hopelessly intertwined with illegal enterprises. Sorting out the clean money from the dirty and the honest citizens from the thugs will be next to impossible, they say.

Before long, some U.S. agents fear, legitimate businesses will become hopelessly intertwined with illegal enterprises. Sorting out the clean money from the dirty and the honest citizens from the thugs will be next to impossible, they say.

“I hate to say it, but traffickers have become bigger and more sophisticated than any one town can deal with,” said Richard Gorman, special agent-in-charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration office in Phoenix. “It’s not just San Luis. Tremendous amounts of money are being dumped into a lot of border towns.

“Vast amounts of wealth and money are involved,” he said. “This isn’t some street-corner trade we’re dealing with. Drug-trafficking organizations today are made up of the best people money can buy.”

Town boosters in San Luis, with a population of 198,780, wince at that kind of talk.

“We are peaceful people who want to work,” said Francisco Olea, president of the economic development committee.

Violent surge

What few deny is that narcotics traffickers are vying for power and influence all along the border. And to further their cause, they hand out tens of millions of dollars in bribes every year, swaying police and politicians in San Luis, Ciudad Juarez, Agua Prieta and other towns, U.S. agents say.

In one case, the late drug lord Amado Carrillo Fuentes is suspected of giving $4 million to the mayor of a Mexican town along the Texas border, a 1997 U.S. intelligence report said.

Mr. Carrillo, known as “Lord of the Heavens” for his pioneering use of aircraft in smuggling, died suddenly last July after extensive plastic surgery at a Mexico City clinic.

Ciudad Juarez was his traditional base, but he had been expanding eastward, taking over territory that once belonged to convicted trafficker Juan Garcia Abrego, U.S. drug agents say.

His death triggered a flurry of gangland-style hits in Ciudad Juarez and other towns as rivals battled for his turf, according to the DEA.

Drug-related violence has become increasingly common along the border. In San Luis alone, dozens of people, including a prominent journalist, have been murdered during the last two years, police say. Alarmed, some residents are calling for a strict curfew and federal intervention.

“We should cry like a baby needing his mother,” said Gregorio Vargas, a San Luis writer. “The violence has to stop. We’ve paid our quota of blood.”

Mixed blessing

When San Luis was founded in 1907, it was a very different place. Neither drug gangs nor a controlled border existed, and the main enemies were the scorching heat and lack of rain; just 3 inches fell per year.

The town’s curse – and blessing with NAFTA – has always been its location on the flatlands of Sonora state. It’s a natural gateway for northbound trade. And for traffickers looking for a discreet spot to land a plane, the possibilities are endless.

“We have the largest airport in the world: the desert,” grumbled Carlos Guzman, head of the San Luis branch of the National Chamber of Manufacturing Industries.

The first trafficker to see the town’s potential was Pedro Aviles, who smuggled thousands of pounds of drugs in the 1970s, U.S. agents say.

“The seeds for narco-political corruption as it exists today were planted and cultivated by Aviles,” said Phil Jordan, a former DEA special agent.

As an undercover agent, Mr. Jordan once struck a deal to buy more than 20 pounds of heroin from Mr. Aviles. Back then, the former agent said, Mr. Aviles paraded around San Luis as if he owned it.

Wearing his trademark leather sandals, Mr. Aviles gave wads of cash to police and flaunted his wealth, sometimes lighting cigarettes with $100 bills.

“In those days, money flowed through the streets,” said Luis Navarro, a former Aviles lieutenant who now runs three drug-rehabilitation centers.

Abundant corruption

Mexican federal police killed Mr. Aviles in 1978, Mr. Jordan said. The motive: A federal grand jury in Phoenix had indicted Mr. Aviles, and his capture could have exposed his contacts. “What Aviles knew was very embarrassing to the Mexican government,” Mr. Jordan said.

Drug corruption remains a problem, U.S. agents say. Texas native Kent Alexander said he discovered that last summer when he went to San Luis to train drug-sniffing dogs. Hours after he arrived, his Belgian sheepdog found 2 tons of marijuana in a truck at a highway checkpoint at 2:33 a.m.

After that, he said, authorities steered him and the dog away from busy trafficking routes so they wouldn’t stumble across any more shipments.

On Aug. 14, 1997, Mr. Alexander said he fled the country, fearing he’d be killed for speaking up about corruption. Now in the United States, he said the Mexican government’s latest strategy – using the military in the anti-drug fight – is failing.

“Soldiers trade their green uniforms for blue ones, but that doesn’t make them honest. Hiding corruption is a shell game,” he said, moving around bags of Big Grab Doritos to make his point. “It all boils down to money. It doesn’t make any difference if it’s widgets, Barbie dolls or Camel cigarettes.”

Gerardo Carranza, the former federal prosecutor in San Luis, denied Mr. Alexander’s accusations.

“That senor is wrong. He doesn’t know the system,” Mr. Carranza said.

Before leaving Mexico, Mr. Alexander met with Benjamin Flores, then editor of La Prensa newspaper in San Luis. Someone had just stolen nearly a half ton of confiscated cocaine from the federal attorney general’s office in San Luis.

Before leaving Mexico, Mr. Alexander met with Benjamin Flores, then editor of La Prensa newspaper in San Luis. Someone had just stolen nearly a half ton of confiscated cocaine from the federal attorney general’s office in San Luis.

Mr. Alexander said informants told him soldiers – some assigned to the attorney general’s office – were responsible. Mr. Flores said poking into such affairs was dangerous, but it was the 29-year-old editor who was in peril.

Gunmen killed him the next day outside the newspaper’s offices. Authorities blamed a local trafficker who was angry because La Prensa said he got special treatment in jail.

The journalist’s friends say he had many enemies and was once sued over a story alleging that a top city politician built airstrips for traffickers.

Reminders

The Flores murder triggered much soul-searching. Townspeople named a street after him. Children organized anti-violence marches. And journalists began saying a prayer before hitting the streets, asking God to “allow my words to defend the noble causes of the people.”

But before long, residents say, it was business as usual. The killings continued. One night, someone fired a shotgun blast into a 31-year-old, then stabbed him with an ice pick. His body was found in a pickup truck parked along the very street named for Mr. Flores.

These reminders of the drug trade riddle a landscape stained with blood. Farmers turn up bodies while plowing fields; marijuana wrappings litter the border where some smugglers cross on foot.

In the case of the stolen cocaine, authorities eventually arrested more than a dozen people, mostly anti-drug agents and soldiers. It was a glaring corruption case: Honest soldiers had seized the coke only to have it snatched back by crooked agents.

Despite such episodes, authorities are undeterred, and the Americans are helping fund the fight with a record $16 billion for counternarcotics in the fiscal year starting in October.

In Mexico, officials are training elite new counternarcotics squads for deployment in San Luis and other towns.

Already, military Humvees are a common sight on dusty San Luis streets. The town is the most violent in Sonora, the state’s judicial police chief says.

Longtime residents call that a smear.

“We’re people who obey the law,” ex-police Chief Conrado Flores said. Most traffickers come from Sinaloa and other states, he said.

“Before, we were like a family,” added Jose Luis Rangel, 51, who moved to Arizona to get away from San Luis crime. “Then these outsiders came and made us the minority.”

Other San Luis natives are drawn to traffickers’ money. Merchants sell silk shirts for $260 and jackets made of crocodile and ostrich-belly leather for $1,560. And bars play folk songs glorifying the slain drug trafficker Pedro Aviles. “They shot him in the back because they could never face him,” goes one tune.

Business strategy

Government officials want the drug culture to disappear. Industry, assembly plants and jobs are what they envision. And San Luis, closer to Los Angeles than the state capital of Hermosillo, is an ideal spot for exports, they say.

If not, they ask, why would Daewoo Electronics sink $100 million into San Luis? The company’s local plant will soon be exporting 2 million TV sets, 1.8 million VCRs and 800,000 computer monitors per year.

“The future of San Luis Rio Colorado is promising,” said Gustavo Montalvo, the state economic development director. “Expectations are very high.”

As for crime, Mr. Montalvo said the clamor for safe streets isn’t just in “San Luis or Mexico. If you were to go to the United States, you’d see there are crime problems there, too.”

Other business leaders agree.

“Crime isn’t out of control, but everything that happens gets more attention now,” said Enrique Orozco, a San Luis developer who is building an 8,000-acre industrial park, expected to be among the biggest in the Americas.

“Officially, drug trafficking doesn’t exist in San Luis,” Ms. Santos countered. “But you can’t deny it’s here. You see all these people with three new cars every year and a nice modern house; you can’t say they bought all that legitimately.

“It just isn’t possible.”