I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on April 14, 1998.

Always the innovators, drug dealers in this dusty border town have come up with a novel way to dispense narcotics: They’ve opened walk-through windows. Indeed, it isn’t difficult to find addicts on the streets of San Luis, with some 100 shooting galleries, rundown shacks and abandoned houses where users inject drugs.

The customer walks up to an abandoned house, forks over $10 or $12, sticks his arm through an opening and some anonymous soul on the other side injects him with his drug of choice.

“It’s a quick way to get a fix,” said a rail-thin 55-year-old recovering addict and former walk-through client. “These little houses are open 24 hours a day. You can get drugs anytime.”

Walk-through windows and other innovations are aimed at feeding a growing number of addicts all along Mexico’s northern border. U.S. and Mexican officials are alarmed by the trend and vow to crack down on rising consumption as part of a new bilateral strategy.

Residents of Mexico’s northern states are particularly worried about skyrocketing drug use, according to a national survey by The Dallas Morning News and the MORI de Mexico polling firm. Eighty-three percent of those surveyed in the north said drug addiction had risen. Nationally, the figure was considerably lower – 66 percent, the poll showed.

Mexican families in the north say they’re also troubled by the violence that often accompanies drug use. Seventy-five percent said they felt threatened by rising crime rates, compared with 60 percent nationally and as low as 43 percent in central states.

San Luis Rio Colorado, a city of 200,000 in the northwestern corner of Sonora state, is one of Mexico’s hot spots for drug consumption, Mexican police say.

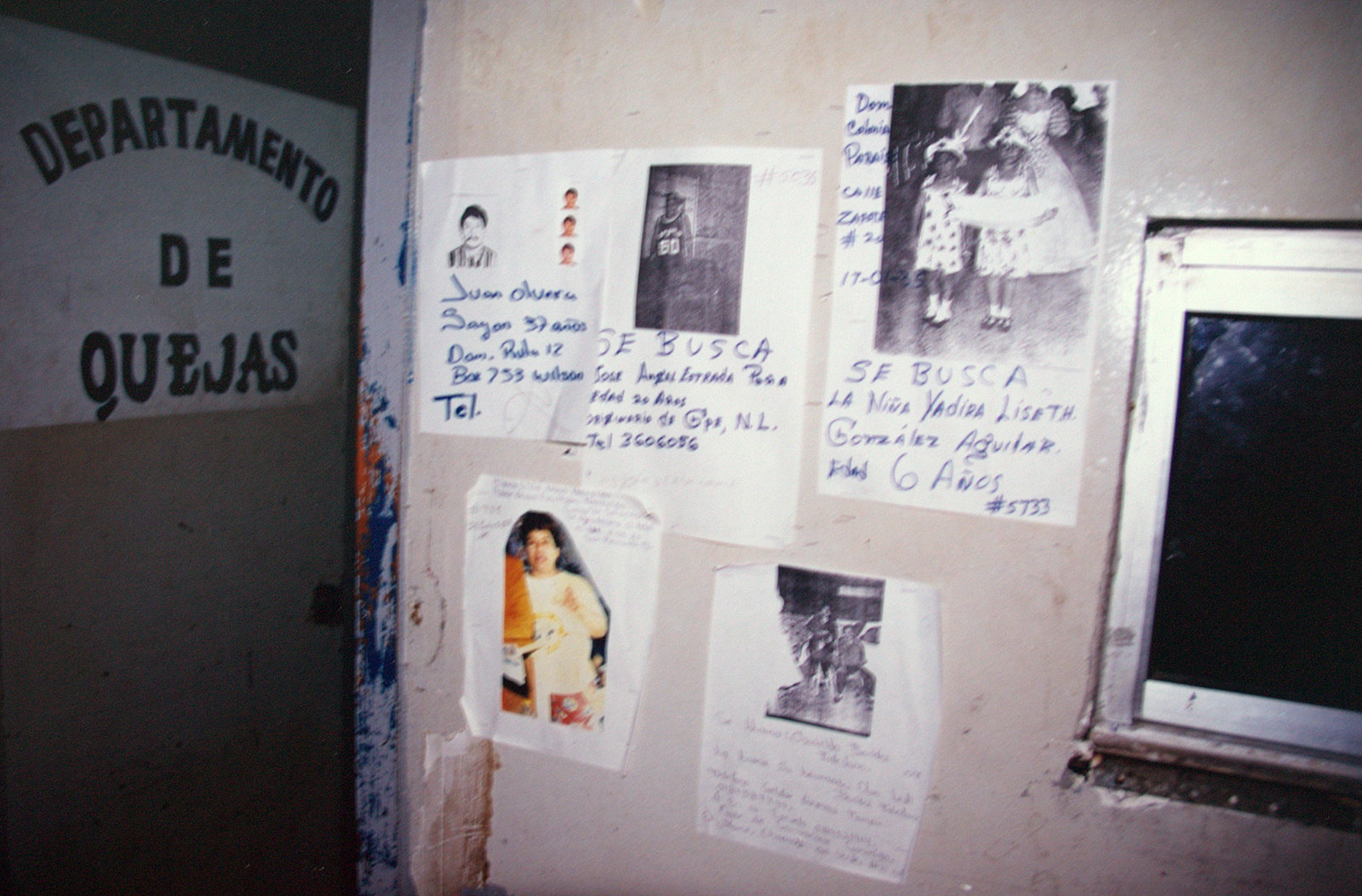

A visit to some of the city’s bustling drug rehabilitation centers helps portray the severity of the drug problem. Crowded and underfunded, the centers are like pockets of resistance under attack during a war, said Luis Navarro, who directs three rehabilitation centers.

“Addicts arrive at all hours, some crying, others yelling hysterically. And more and more of them are teenagers,” Mr. Navarro said.

“I had one kid come in who was 14 and said he had been using heroin since the age of 9,” he said. “It’s not like it was in the ’70s. Back then, if you wanted heroin, the hard stuff, you had to cross the border into Arizona to get it. No more. Now you can get drugs on practically every street corner.”

Not even the police are immune. Last December, 63 officers – almost half the municipal force – were suspended after failing drug tests.

Federal authorities say drug use has climbed not only along the border, but also in Mexico City, where an estimated 40 of every 1,000 youths used cocaine in 1997, compared with 15 of every 1,000 in 1993.

An even higher share of the population is believed to consume drugs in San Luis Rio Colorado, although local officials say precise numbers are hard to come by.

“Our youth is all wrapped up in vice,” said Petra Santos, a leader of the town’s left-leaning Party of the Democratic Revolution. “They use a lot of drugs, and that leads to crime, including robberies, murders. I mean, it’s not unusual anymore to have two or three cadavers suddenly turn up.”

Overall drug usage in Mexico remains low.

Overall drug usage in Mexico remains low.

Fewer than five in 1,000 citizens are thought to consume narcotics, as compared with 60 in 1,000 Americans, according to U.N. estimates. Still, U.S. and Mexican community leaders along the border are worried.

Town officials in San Luis estimate that local addicts, thought to number at least 6,000, are responsible for 80 percent of all reported crimes.

Methamphetamine, nicknamed cristal in Mexico, is the latest rage.

“I think cristal is the most dangerous drug there is,” Mr. Navarro said. “It does more damage to your body and it does it faster. You don’t need to do drugs for 15 or 20 years to destroy your brain and end up in a nut house. With cristal , you can do it in a matter of months.”

He pointed out a patient at one of his centers in San Luis.

“Hey, come over here,” he told the man. “What’s God’s phone number?”

The man rattled off a number.

“So if I call there, I can talk to God?” Mr. Navarro asked.

“Yep,” the man said.

Mr. Navarro turned toward another group of recovering addicts.

“I call these the tronados . That means their brains are wrecked, mostly from doing drugs, especially cristal .”

For a 12-cent tip, one fellow sang a folk song about the late Pedro Aviles, a notorious San Luis drug trafficker who was active in the 1970s.

“He remembers every lyric,” Mr. Navarro said. “But that’s about all he knows. His brain is fried.”

Mr. Navarro runs two rehabilitation centers in San Luis and one in nearby Mexicali, tending to about 400 patients in all. The fee for three months’ treatment is 400 pesos, or about $48. The tiny centers are crowded and have few of the comforts of home.

“Living here is very tough,” Mr. Navarro said. “You have to want to get better.”

Patients must rise at 6 a.m. They’re not allowed to leave the premises during the first month, and violent behavior is forbidden. Case in point: Two young toughs who threatened to start a riot last year were forced to wear flowered dresses and were cuffed at the wrists and ankles for everyone to see.

Church groups and business people on both sides of the border donate food and money to help keep the centers afloat. But Mr. Navarro said it is tough to get by.

“We live day by day with God’s help,” he said.

Mr. Navarro said he sometimes sends his patients to warehouses to unload produce in exchange for a few crates of vegetables or eggs. They once found 3 kilos of marijuana while unloading crates of tomatoes off a truck.

“The authorities had seized the truck after finding drugs, but they missed the 3 kilos,” Mr. Navarro said. “They were shocked when we – a bunch of drug addicts – returned it to them. Grateful, too. They ended up giving us the whole truckload of tomatoes.”

Despite such gestures, Mr. Navarro, who used drugs and drank alcohol for 33 years, said coming clean is difficult. And he said many of his patients wind up back on the streets using drugs.

“Drug addiction kills dreams,” he said. “It closes your mind, and sometimes not even an atomic bomb is strong enough to open it.”

Many of those at the center said they paid for drugs by stealing.

“I robbed my mother, my father, my brothers. I cheated people on the streets. I was always stealing, stealing and stealing,” said Alfredo Fernandez, 35, now assistant director of the centers in San Luis. “I did all kinds of drugs – alcohol, pills, mushrooms, acid, heroin, cocaine, cristal – an entire pharmacy.”

One day, he said, his mother told him she was going to give him a present. He thought she was going to part with some family land, which he planned to quickly sell to buy more drugs.

“Instead she gave me papers showing she had bought two coffins – one for me and one for her,” he said. “It was her way of telling me that if I didn’t stop using drugs, I would kill myself and that it would kill her, too. I started to wake up after that.”