I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on May 21, 2000.

Lost in the rumble and grit of passing rail cars and tractor-trailer rigs is a quiet place where angels live.

The tiny winged creatures peek out from cubbyholes and corner tables, standing guard as Beatriz Jordan lights a candle for her dead son. Then she pours him a fresh glass of water.

“This is where Bruno lives,” she says. “Here with the angels.”

Five winters have passed since an assailant killed the popular pre-law student in a carjacking. Yet even now, the murder continues to claim victims, wrecking lives and families like a curse. Beatriz Jordan, 76, and her husband Antonio, 79, agonize over Bruno’s murder as their twilight years rush by.

Their youngest son – the heart and soul of the Jordan family – was gunned down at 27 and the killer ran free. “It’s so unfair,” she says, crying.

The couple’s oldest son, Phil Jordan, a former U.S. drug agent who lives in Plano, is convinced that Mexican drug traffickers ordered the killing to intimidate him. Haunted by guilt, he has tried to solve the slaying himself, a quest that wiped him out financially and helped destroy his second marriage.

“The darkness” is how he describes what he’s been through.

Fellow drug agent Sal Martinez – cousin to both Phil and Bruno Jordan – is another tormented soul. He says he never cried harder thanat Bruno’s wake, but kept the pain inside after that.

Relatives were stunned when the FBI in December charged Mr. Martinez,37, with plotting to avenge Bruno’s death. The agent denied the charges at first. “If I was doing something like this, call the loony farm and have me committed,” he said days after his arrest.

He later pleaded guilty, saying he didn’t want his family to endure a trial. And next month, he leaves for a new home: Federal prison, where he’ll spend seven years. “The brutal death of my cousin … led me to think with my heart instead of my head,” he told a Laredo judge.

It’s a familiar tale of immigrant families, blood ties and revenge.But the backdrop this time is the rambling U.S.-Mexico border, a modern-day Casablanca, a place of wanderers and workers, killers and crooks, men of the law and men of the cloth.

With its multihued blend of humankind, the border often brings out the best in people, the unrelenting desire to work and dream. But somesay it also can bring out the worst, the bitterness, the urge to kill. And sometimes, as the Martinez and Jordan families found out, the line between good and bad can become confused.

* * *

If this crime saga has a beginning, it might as well be that cold January night in 1995 when Bruno drove to an El Paso Kmart to drop off a friend’s new Ford Silverado.

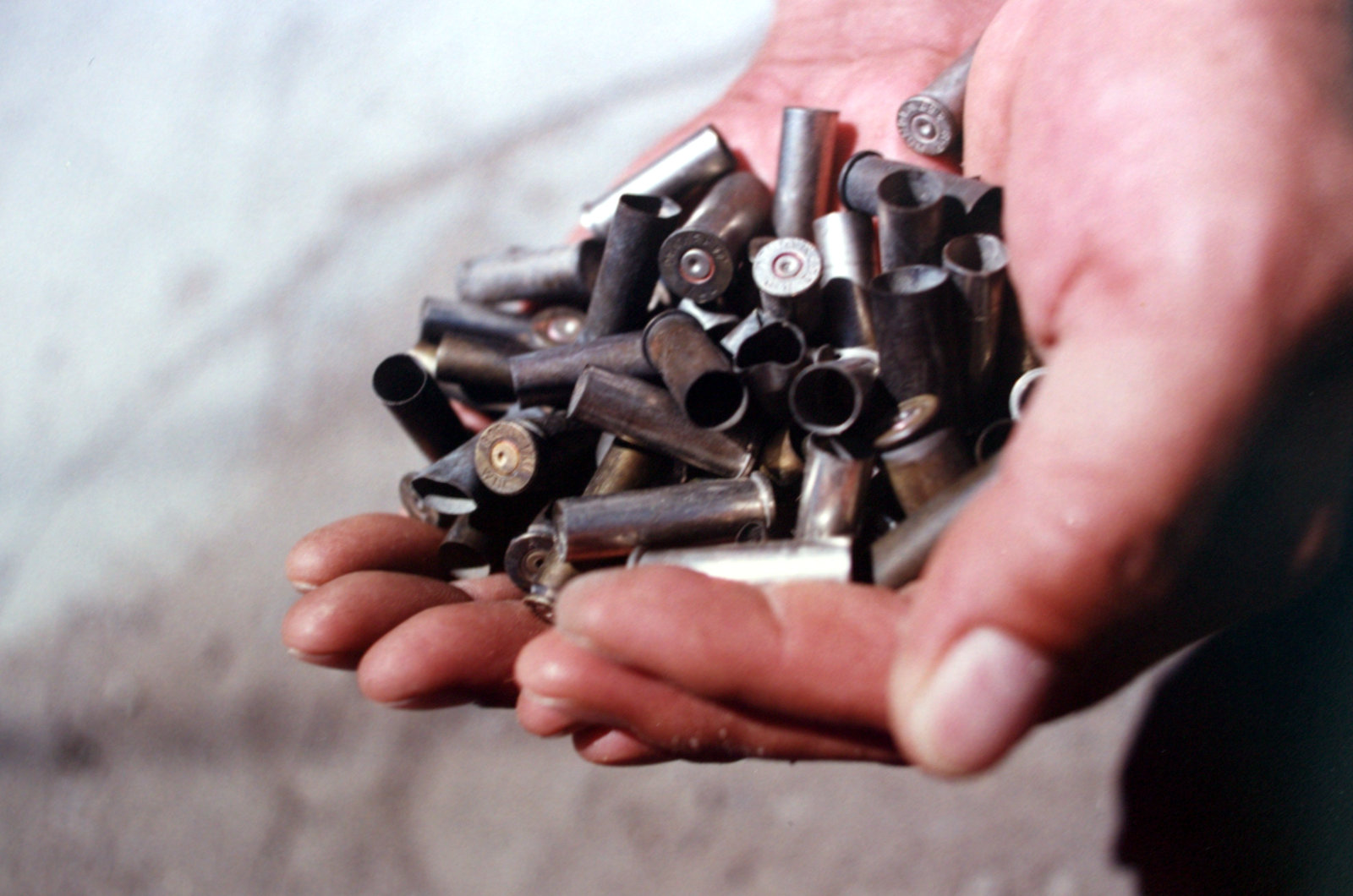

Suddenly, someone jumped out of a black pickup truck and shot him with a 9mm pistol. Bruno, alone that night, staggered to the back of the Silverado. The assailant fired again and Bruno was dead.

Now, on another crisp January night five years later, his mother is in the kitchen stirring a pot of beans. Her son, Phil, hugs her and settles his broad, 6-foot-3 frame onto a chair.

He’s back on Frutas Street, where he once swatted baseballs and played cops and robbers. The familiar scent of beef tacos wafts through the air as it has, well, just about forever. But he’s not feeling too nostalgic.

At 57, he’d like to slow down and worry less, but he can’t. He’s angry. He gave his life to law enforcement, but when he needed something in return, a meager shred of justice, he says, he got nothing.

The prime suspect in his brother’s murder was a Mexican teenager  nicknamed “Smurf.”

nicknamed “Smurf.”

“Yeah, I’d like to strangle the kid,” Phil Jordan says, raising a big set of hands. “Would I squish him? Would I have the guts?”

No, he finally decides.

“I won’t endanger my children, my life, for a low-life punk.”

Outside, trucks rumble along Frutas Street, once lined with green lawns and shrubs. Warehouses and asphalt have since spread across the neighborhood. And the eight-lane Bridge of the Americas, leading into Juarez, Mexico, looms nearby.

Not so long ago, this was a bustling neighborhood where many immigrants settled, eager for a piece of the American dream. Phil’s grandfather, Eugenio Levini Forti, left Italy and moved to Frutas Street around 1915. He opened a store and sold clothes, “Forti’s Devils” chili peppers and other goods to Mexican laborers.

He married a Mexican immigrant, and soon the family’s Italian roots began to blend into the Mexican-American neighborhood. Phil says Mr. Forti often spoiled his grandchildren with big scoops of ice cream, but he also demanded that they make something of themselves.

“No way I could tell my grandfather I wasn’t going to college,” he says.

Phil was a straight arrow even then.

“Just a big, gangly, lovable kid with a burr-headed flat-top,” says his former basketball and baseball coach, H.R. Moye. He never touched drugs and if he ever drank more than a 12-ounce beer in a sitting, friends don’t remember it.

In 1965, Uncle Sam recruited him into the agency that would becomethe Drug Enforcement Administration, or DEA. He would soon be on the front lines of the international drug war.

But first, his sister recalled, the young agent summoned relativesand said, “You know what my job is now. If I know you do drugs or selldrugs, I’ll bury you.” The message was clear: No one’s above the law, not even family.

* * *

Twenty years younger than his cousin, Sal Martinez – Mike to old friends, Sal to most everyone else – came from a different generation. He identified more with Sonny Crockett of Miami Vice than Sheriff Andy Taylor of The Andy Griffith Show.

But he was an obedient kid. And when the neighborhood bully picked onhim, he asked his mother’s permission to fight back. “Hit him so hard he never hits you again,” Nelly Martinez told him.

The boy went out and did it.

“He’s not scared of people, but he’s not aggressive, either,” says Tony Calderon, 37, a pal since they were toddlers. “If anyone has a good heart, it’s Mike.”

At El Paso’s Ysleta High School, the teen went out for football.

“He wanted to play with the bigger guys,” says his father, also named Salvador Martinez. “He said, “Dad, I can take the shots.’ ”

Mr. Martinez was soon a star cornerback, and the Class of ’80 votedhim its most popular student. In 1985, he became a Texas state trooper and was quickly drawn to the excitement. “I think he got his degree in high-speed car chases,” jokes his father, a retired bus driver.

After a stint with the U.S. Customs Service, Mr. Martinez joined theDEA. And life was good – until Bruno’s murder.

* * *

Lionel “Bruno” Jordan was the “baby” of the family. Four children came before him. At 44, his mother hadn’t expected a fifth. “But when Bruno was born, we were so happy,” she says.

“I used to take him to work and show him off,” says her husband, Antonio.

By high school, Bruno had grown to a strapping 6 feet and won a “best legs” contest. “Girls followed him just to touch his legs,” an aunt says.

Phil says he and Bruno were close even though 25 years separated them.

“I knew he was my brother, but it’s almost as if he were an older son,” he says. “He was always volunteering to do things for other family members, like fill out tax returns. He looked after my own children and his parents, too.

“He had this charisma about him. He was the counselor, the head of the family. We expected some great things from Bruno.”

Bruno worked at Men’s Wearhouse in El Paso to pay for school and dreamed of becoming a prosecutor. He also wanted a family, and he and his girlfriend, Patricia Avila, planned to marry sometime in the summer of 1995.

He was killed on Jan. 20, 1995. Neither the Ford Silverado he was driving nor the gun was ever found. But within a half hour, police arrested a suspect, Miguel Angel Flores, then 13 and from Ciudad Juarez, just across the border.

The boy initially confessed to the killing but later denied involvement. And Mexican officials, worried he’d be railroaded, helped in his legal defense.

The case wound its way through court for years. During the second of three trials, in May 1995, the boy’s mother said her son was a “goodkid” who washed car windows and juggled to earn grocery money.

Jurors voted 12-0 to convict the boy of murder, and a judge gave him 20 years. But there was a problem with State’s Exhibit No. 12, the jacket allegedly worn by the boy. A juror found something police had missed: A marijuana cigarette in the left pocket’s lining.

The joint made the boy look guilty, his lawyer argued. The judge let the verdict stand, but that decision was later overturned. In the third trial, jurors voted 11-1 to convict, but since the vote wasn’t unanimous, the judge ruled a mistrial. So after four years in jail, the teenager was freed and went to Mexico.

Phil Jordan dug deeper into the case and says he found Smurf wasallegedly part of a car-theft ring linked to a Juarez drug gang. Hesuspects gang bosses may have ordered Bruno’s murder to hurt him at DEA, but he has no concrete evidence of that.

The killing occurred just three days before Mr. Jordan took over as director of the El Paso Intelligence Center, the world’s largest narcotics intelligence outfit. Traffickers might have been sending him amessage, some of his agent friends say.

If so, it didn’t work. Mr. Jordan only became more outspoken about drug corruption in Mexico, angering DEA brass.

Then, about six months after Bruno’s murder, Phil left the agency. Thirty years in law enforcement was enough, he says. But he was also fed up with U.S. drug policy. American authorities, he says, care more about free trade with Mexico than cracking down on the drug cartels.

“Drug traffickers are the single most significant threat to U.S. national security,” he says.

* * *

Sal Martinez was much closer to Bruno than to Phil. The cousins hung out during family gatherings and were much better friends than Phil says he ever realized.

But Phil and Sal did have one thing in common: A firm belief that drug traffickers were about the lowest form of human existence. And over some relatives’ protests, Sal volunteered for a perilous undercover assignment in Mexico.

“Sal would have given his life for the DEA,” his wife, Suzie, laments. It was always DEA first “and then me.”

Loyalty to country seems to run in the family. The agent’s grandmother, Felipa, flatly refused when her immigrant neighbors in El Paso told her to take down the American flag on Mexico’s Independence Day in September.

“Why not?” they asked.

“Because this is where my hunger ended,” she said.

Mr. Martinez was also patriotic, an agent friend says. Fearless, too, but “too damn trusting.”

Mr. Martinez was also patriotic, an agent friend says. Fearless, too, but “too damn trusting.”

His job required him to schmooze with Mexican agents, but Mr. Martinez sometimes went too far, taking them drinking, the agent says.

If Mr. Martinez had been an insurance agent from Peoria and not a drug agent from the raucous borderlands, things might have been different. But he grew up seeing life’s rough side. He saw what traffickers did: Daylight executions, bodies dumped in ditches, hands and feet bound, signature gunshots to the head and chest.

Residents in El Paso, a hot drug corridor, often suspected who thegangsters were. A man named Vicente Carrillo, a boss in the Juarez gang, would venture into town in his sleek green Lexus. People whispered about the $100 bills he threw around, but they asked few questions.

Mr. Martinez had to ask questions, which was risky business. A gang of traffickers and corrupt cops once swept in with automatic weapons andthreatened to kill him, he says, while he was alone in Juarez investigating a multi-ton drug load.

“I was ready for a shootout,” he says. “I had my submachine gun and pistol with me. If anybody had popped off a shot, it would have been a bloodbath. I was always putting my life in danger. Instead, they kill Bruno, a nice guy who sells suits for a living.”

* * *

In September 1999, Sal Martinez drove to an Exxon gas station in McAllen, Texas, and met with Jaime Yanez, a Mexican state police chief he had gotten to know a few years earlier.

The agent handed the police chief an envelope. Inside was a Polaroidphoto of Smurf. Mr. Martinez allegedly asked the commander to arrange Smurf’s murder. Instead, the cop told the FBI about it.

Later, the commander secretly taped Mr. Martinez. The DEA agent allegedly showed him a pistol – a blue-steel .38-caliber Colt – andpromised him at least $10,000, the FBI says.

The FBI arrested Mr. Martinez on Dec. 14. Days later, the agent said he was stunned. “My emotions were misinterpreted and built into a criminal case … I’m not a criminal,” he says.

Phil lashed out at U.S. authorities.

“If the FBI had spent a fraction of its time investigating the carjacking murder of my brother, maybe we wouldn’t be in this predicament,” he says.

Top DEA officials were quick to condemn Sal. But many agents backed him. DEA Watch, a Web site that posts the views of special agents – S/A’s – reported the latest buzz.

“The only criticism I have for this S/A is that he did not do the job himself,” an agent wrote Dec. 14.

The Watch also told agents how to help Mr. Martinez with his legalbills. The feeling then was that the FBI had set him up. And while theFBI won’t comment on that, prosecutor Mary Lou Castillo points to a single fact: On Feb. 3, Mr. Martinez pleaded guilty.

“People who are truly innocent are not going to rush to plead guilty,” she says.

Mr. Martinez says prosecutors played hardball, telling him they were going to pile on more charges if he didn’t cave in.

“I only had 48 hours to decide,” he says. “It was, “Take the deal now.’ ”

“It’s too scary to try to fight it in court,” says his wife, Suzie. “It would have been too messy.”

* * *

Back on Frutas Street, Beatriz and Antonio Jordan are in the white frame house where they’ve lived since 1947. The trucks have stopped rumbling by, and only the distant sound of barking dogs breaks the night air.

Beatriz has turned Bruno’s old bedroom into a shrine of sorts. His books on Texas penal code and cracking down on teen offenders are in a neat row, and his old lottery tickets are in a box. Relatives sometimes play his favorite numbers … 746 and 835.

A poem – a tribute to Bruno – is on a wooden dresser. “You are where the sun never sets, where the wind is no longer cold, where peace of heart, soul and mind are one,” it says. “You are our future.”

Beatriz says she sometimes tells the priests and nuns at church how much she misses Bruno. She also has her angels, some arranged so they appear to gaze at photos of her son. And she’s sure Bruno hears her when she prays.

Of course, that’s not enough. She says she wants him back, then starts to cry. “It helps. I need to talk about it.”

But no one believes she’ll ever be the same. And even though she and her husband built a new home away from the barrio, they don’t plan to leave the house where angels stand guard.

“I can’t,” she says. “This is where Bruno lives.”