The U.S. ambassador’s telegram was urgent, warning that hostilities were spreading quickly and Americans were in danger. The embassy decided to carry out “emergency evacuation plans at once for practically all of China.”

Three days later, Jay Brownlee Davidson and his wife, Jennie, joined hundreds of other Americans who were fleeing Nanking, now called Nanjing.

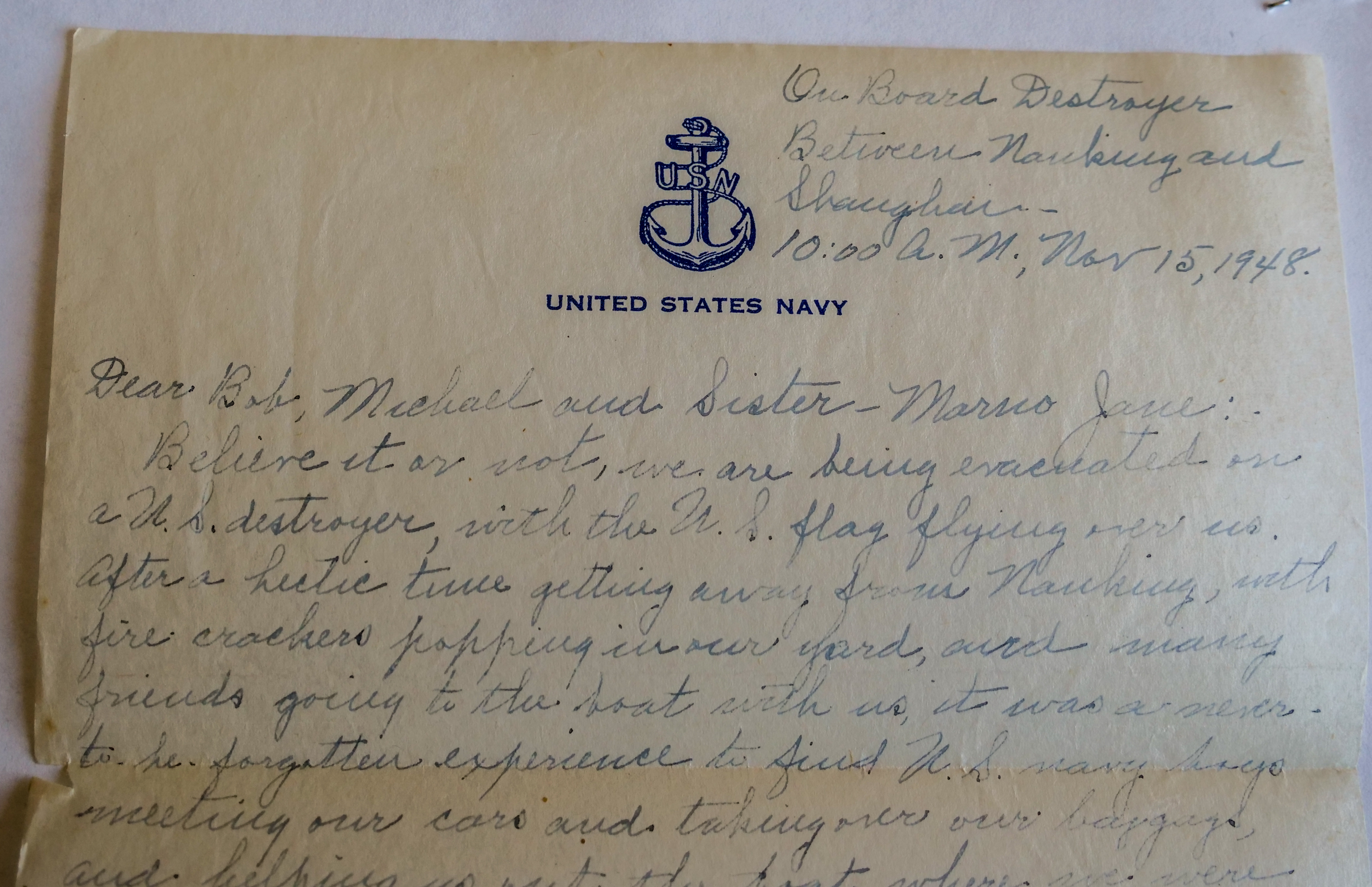

“Believe it or not, we are being evacuated on a U.S. destroyer with the U.S. flag flying over us,” Jennie wrote in a Nov. 15, 1948, letter to her children.

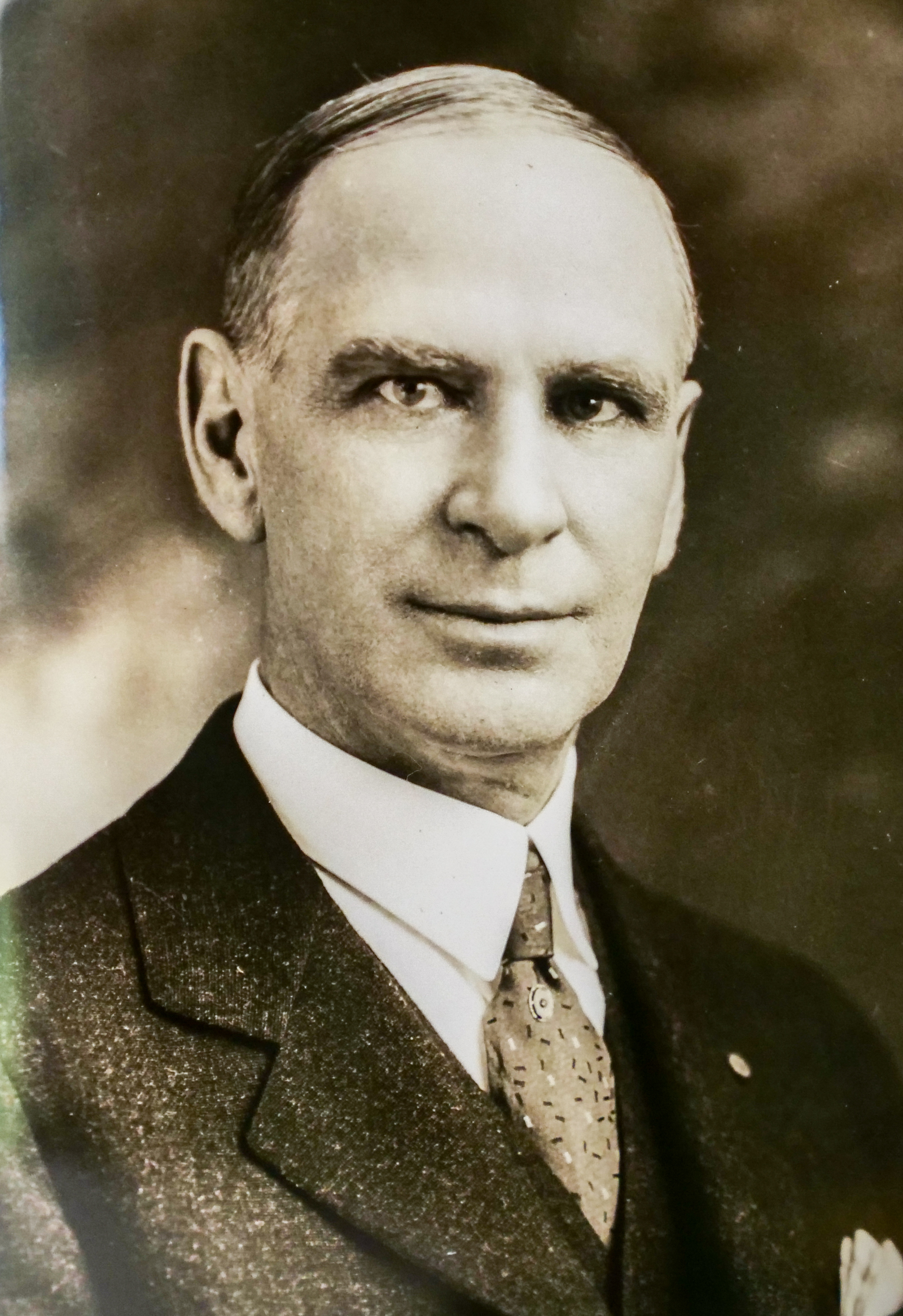

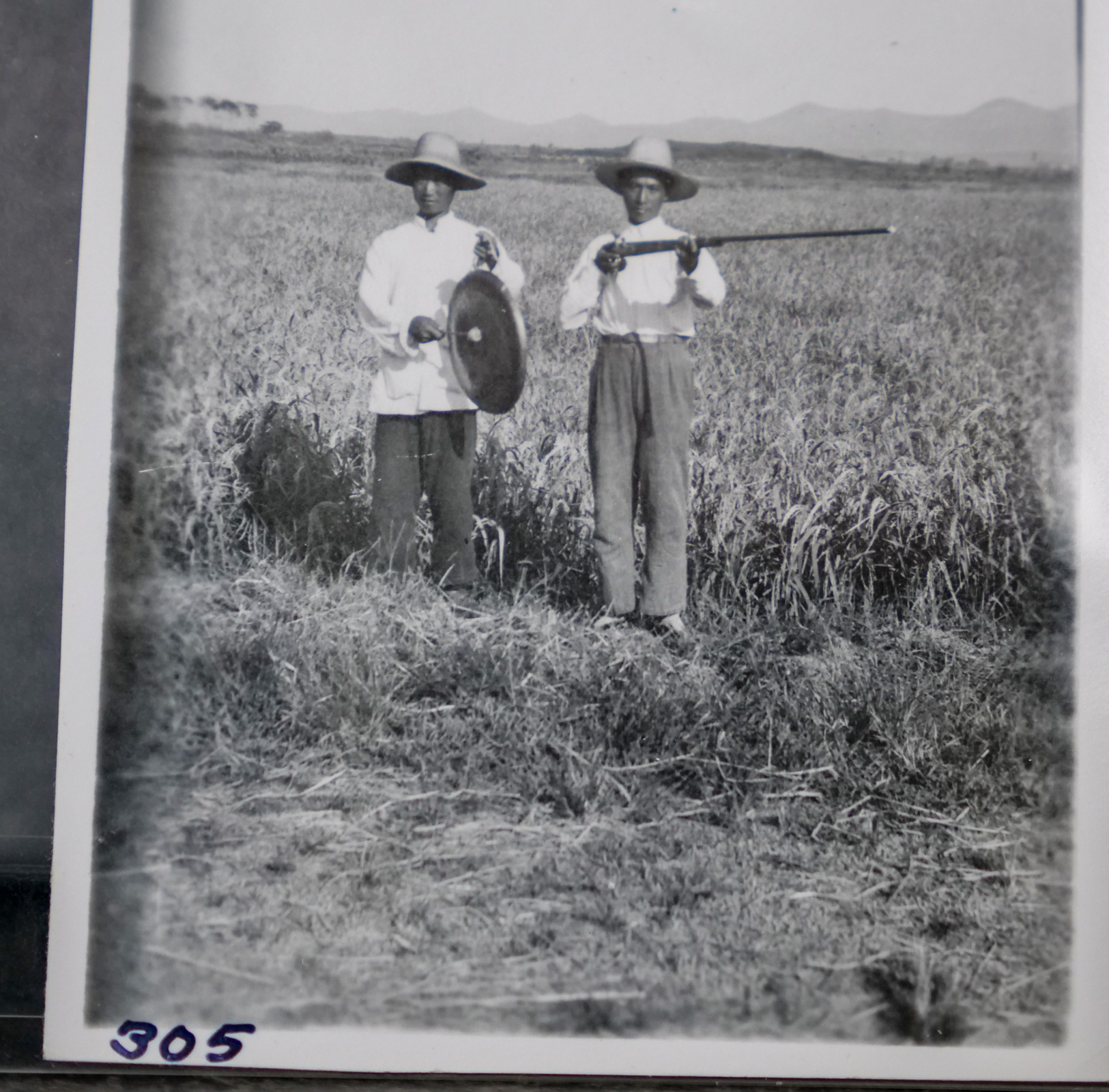

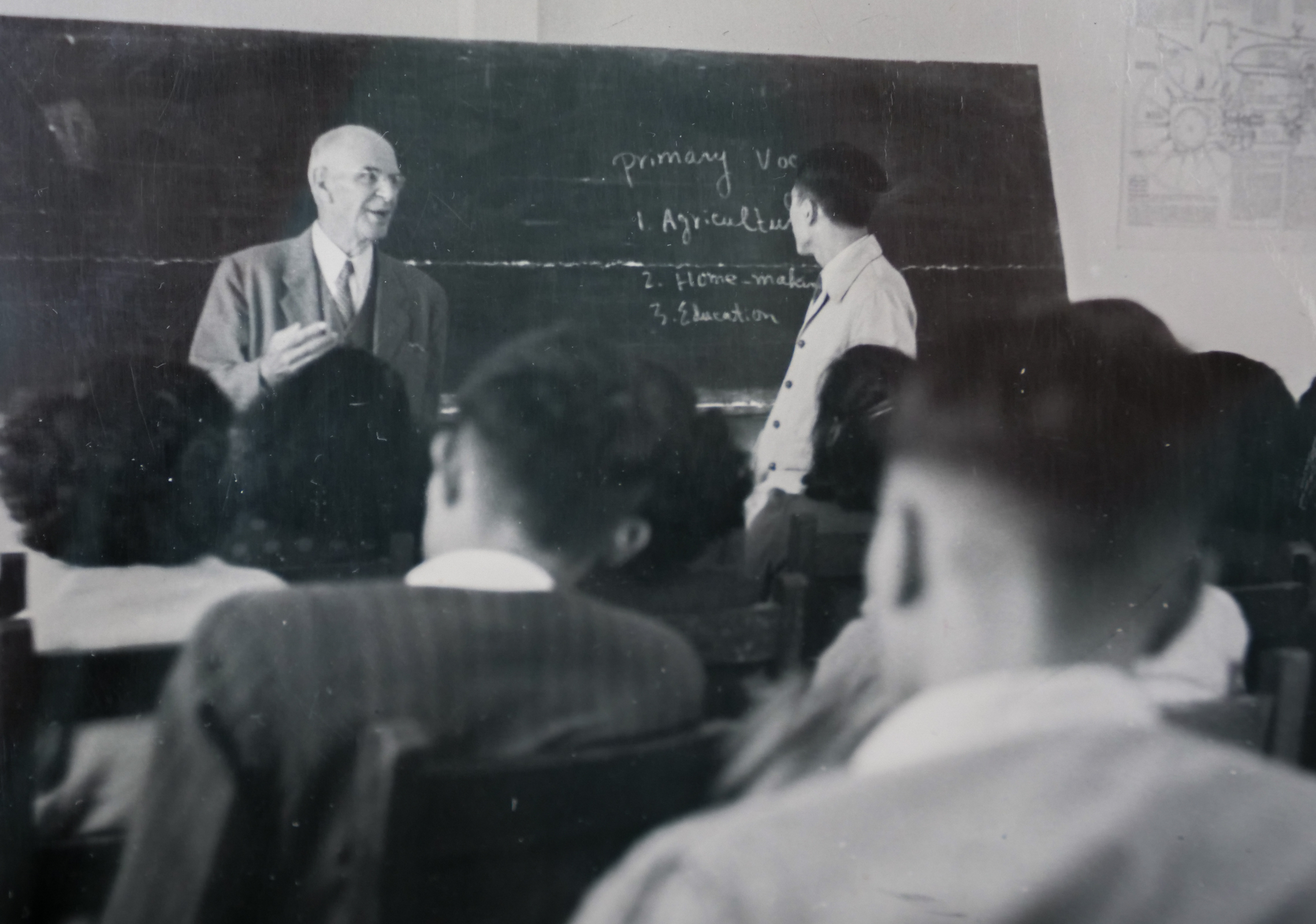

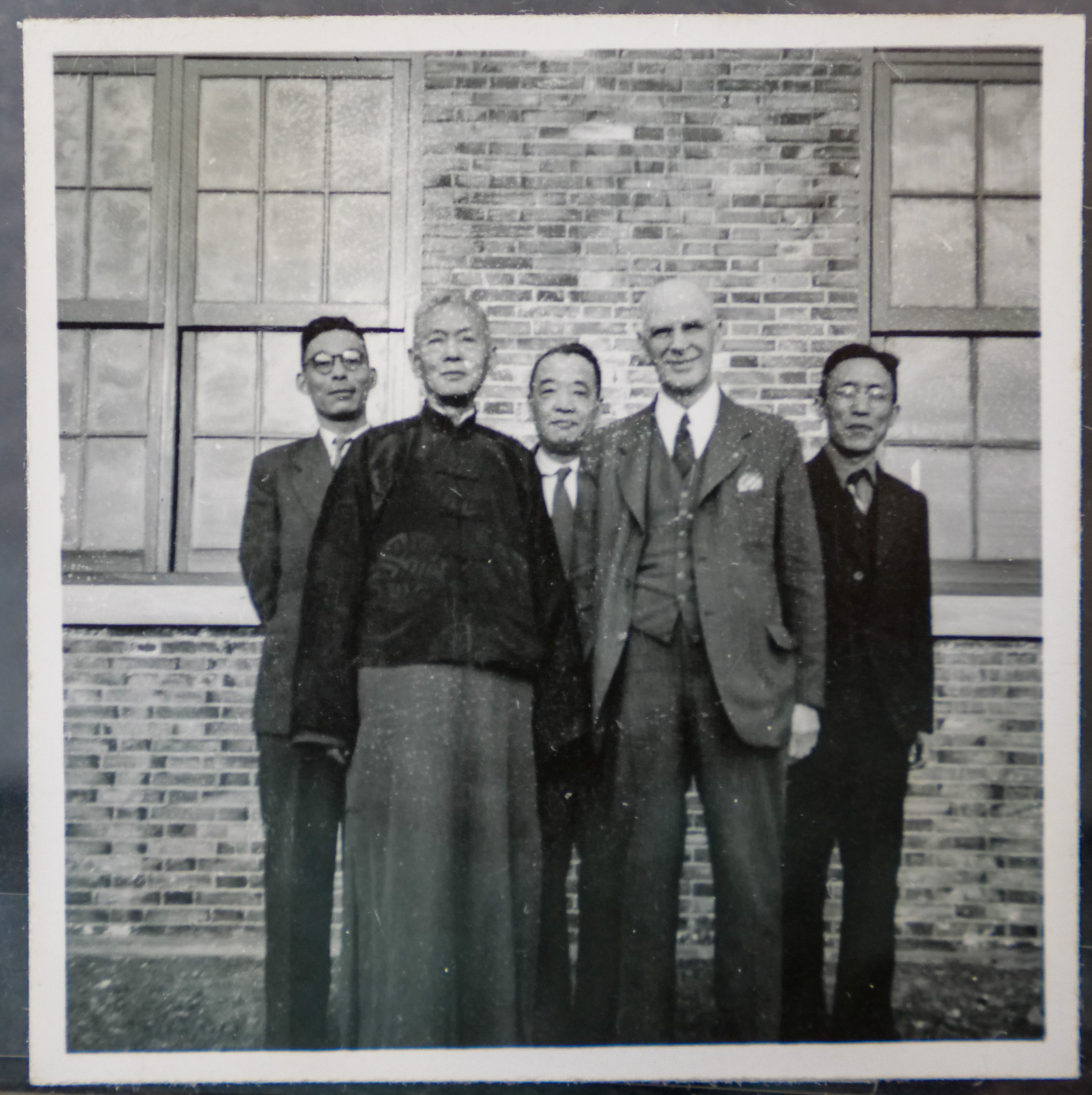

Her husband, a college professor who pioneered the field of agricultural engineering, had arrived in Nanjing nearly two years earlier to share modern farming techniques with the Chinese. Now he and Jennie were rushing to leave as Communist forces swept across the country.

Last month, I went to Iowa State University where Prof. Davidson worked to look through archives he left behind and to learn more about his story. Davidson, known to his family as Lee, was my great-grandfather.

I decided to dig into Davidson family history after teaching at China Foreign Affairs University in Beijing last year and exploring Nanjing and other cities.

Below is some of the material I have gleaned from university archives, family letters, newspaper articles, documents and other sources. These scattered bits of information, arranged in chronological order, give you a glimpse into my great-grandparents’ journey.

According to Iowa State University, Lee was “internationally renowned as an expert on agricultural mechanization.” He was granted at least five patents for farm-related equipment and wrote three textbooks about agricultural engineering. I chose to focus on his 21 months in China, which he once described as “his greatest honor and most interesting experience.”

Early life

Feb. 15, 1880 – Lee was born in Douglas, Nebraska. He was the youngest of seven children and began working on the family farm at age 16. He and his brothers and sisters attended a rural church that his parents helped establish.

June 9, 1904 – Lee graduated from the University of Nebraska with a degree in mechanical engineering.

1905 – Lee began working as an assistant professor of agricultural engineering at Iowa State College in Ames, Iowa. Graduations were held in a tent, and horses and buggies navigated the dirt streets.

June 14, 1906 – Lee married Jennie Baldridge after meeting her on a blind date. Her father was Irish and served in the Army during the Civil War.

April 20, 1907 – Lee and Jenny had their first child, Margaret Elizabeth.

Jan. 1, 1909 – Ethel Brownlee, their second child, was born.

California: Adventure and Heartache

April 30, 1915 – Lee took a job as a professor of agricultural engineering at the University of California. His salary: $3,700 per year. Margaret was about 8 years old when they traveled to California.

“In those days this was an adventuresome thing to do,” Margaret wrote many years later in 1980. “The automobile was a 1914 Ford. A crank in front started the motor. The headlights were lighted with a match and when they dimmed, father reached out and pumped the pressure in the gas tank on the running board. When it rained, sliding glass curtains were buttoned in place. If there was a question about gas supply, occupants of the front seat got out, lifted the cushion and measured the gas in the tank with a ruler. We carried a canvas bag or two of water – for the car.

“Highways were pretty primitive. Sometimes they were muddy trails. Out in the West the markings were scarce. Once we looked for the red, white and blue paint bands that identified Lincoln Highway, found them on a telephone pole on the far side of a wind-swept flat area.

“Father devised an ‘RV’ (recreational vehicle) much ahead of its day. At night we slept in the car. Father built a mattress support that rested on the backs of the front and back seats (it was rolled up and carried in that running board in daytime). Mother and father slept there. My sister and I slept down below on the two cushioned seat.

“The trip from Iowa to California took about ten days of driving. We were real pioneers seeing America – and had a great time.”

While Lee and Jennie were in California, tragedy struck. A son, James Vincent, died in 1915 at just seven months. A daughter, Helen Mary, died in 1918 at age 2 – a victim of the Great Flu of 1918 which killed millions of people around the globe.

Back to Iowa

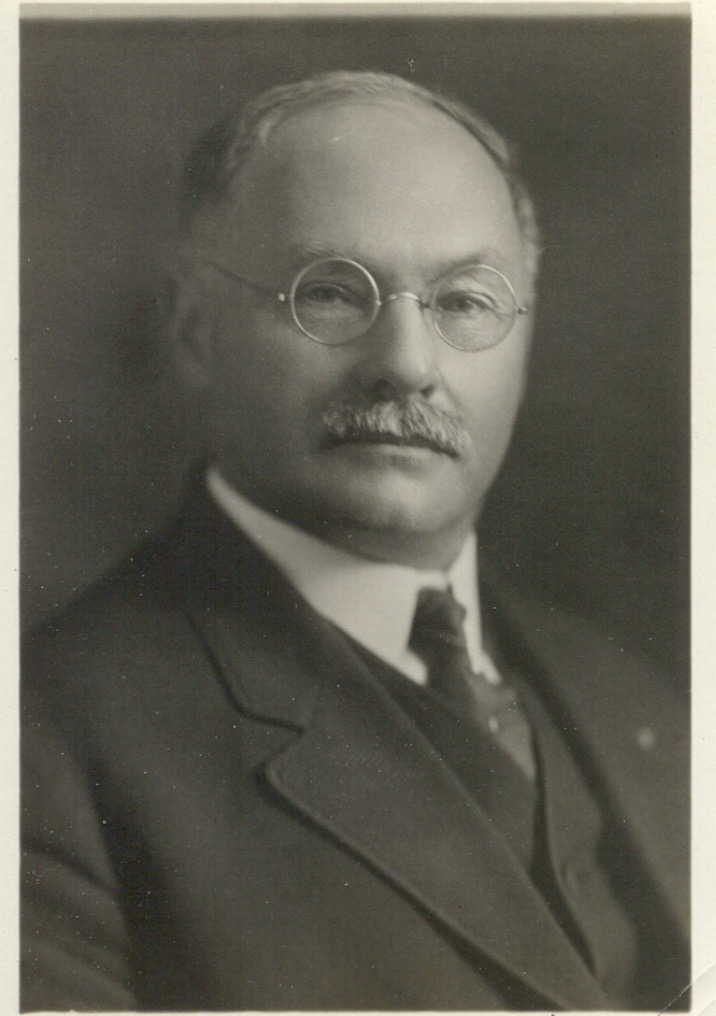

1919 – Lee and Jennie returned to Iowa State College, now called Iowa State University. Lee led Iowa State’s Department of Agricultural Engineering for decades. Some years later, Iowa State Dean Emeritus Anson Marston wrote:

“Professor Davidson is one of the finest, ablest and most modest of the many outstanding men with whom it has been my good fortune to have been associated during 80 years of life. We have been personal friends for 39 years. We have been members of the same faculty and the same church for 35 years.

“… Professor Davidson and I are both engineers… He has been foremost among the creators of a new branch of our profession – Agricultural Engineering. He was a farm boy before going to college and could realize the great importance of the close association of engineering and agriculture. For thousands of years farm work was hand work and was associated with drudgery, and farm life was isolated from the modern conveniences and other advantages of town life. This situation has been revolutionized by the application of engineering to agriculture in farm machines, farm structures, land drainage, irrigation, good roads, autos, telephones, radios, electricity, water supply, sewerage, and heating.”

Lee directed farm machinery surveys and was a consultant for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other organizations. He even met with President Calvin Coolidge on Sept. 2, 1927.

He also spent time trying to help out ordinary people. For instance, a lady from Storm Lake, Iowa, wrote his college department with this request: “We are planning to build a hen house for 300 or more hens. Will you kindly send us some plans for such a building for this part of state?”

First Russia, then China

1929 – Lee spent four months in the Russian Far East. He traveled 32,000 miles while four months investigating conditions for persecuted Jews sent to the region to resettle and work in agriculture.

Jan. 24, 1947 – Lee and Jennie climbed aboard a former Naval transport ship called the USS General M.C. Meigs and set off for China. He was three weeks shy of his 67th birthday. She was nearly 64 years old.

Feb. 4, 1947 – Jennie wrote a letter to Mike Eaton, her 7-year-old grandson, from aboard the ship. She said she was 1,582 miles from Shanghai, which would have been less than three days away if the ship traveled at its top speed of 24 miles per hour. But Jennie said they were moving slowly.

“To Mikie,” she wrote, “we are not going fast because of the rough sea. It looks like mountains and the spray blowing across the waves looks like dust. It is something to remember.”

Feb. 8, 1947 – Lee and Jennie arrive in China, according to a stamp in his passport.

“Westernization” of Chinese agriculture

Lee headed a committee that included three other American experts, Archie A. Stone, Howard F. McColly and Edwin L. Hansen. The four men and their wives planned to stay in Nanjing for 2 1/2 to 3 years. International Harvester financed their trip. The company, along with 24 other U.S. firms, also donated tractors and other equipment for their use.

Life in Nanjing

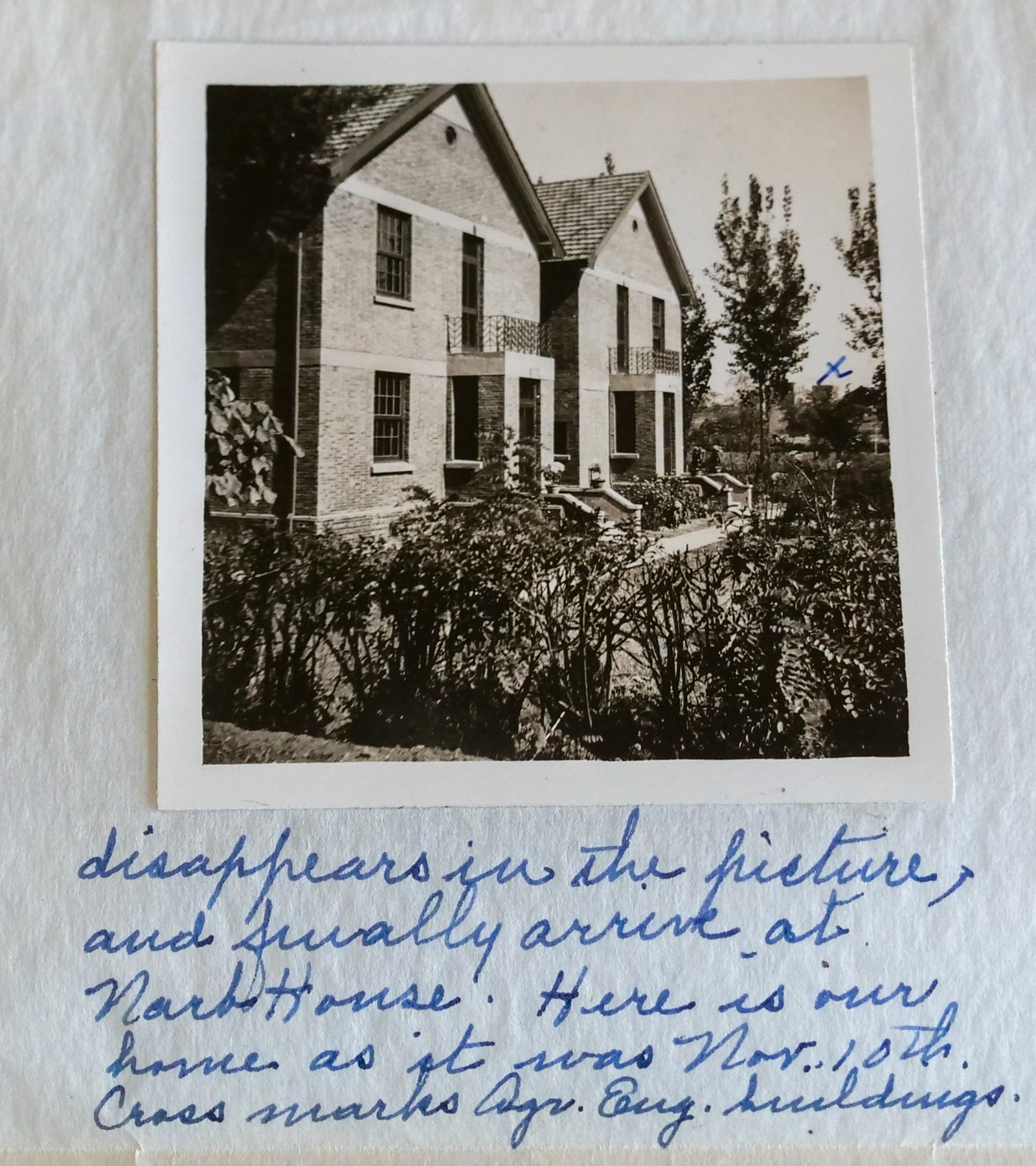

Lee and Jennie settled into a seven-room brick home built for them and the McCollys at the National Agriculture Research Bureau five miles from Nanjing’s city wall. Each family had a cook, a houseboy and a maid, along with a vehicle and driver.

July 24, 1947 – In a letter to her daughter, Margaret, then 40, Jennie said the weather in Nanjing was brutal. She called it “the Great Heat.”

“The temperature has not been above 90 degrees but it is very humid and usually there is no breeze at night,” she wrote.

July 25, 1947 – A day later, Jennie wrote of “a great hubbub” that occurred at 3 a.m.

“Two of the night guards went asleep on our front porch and two others found them there,” she wrote. “No doubt the two sleepers have been reported and will be called on the carpet. Such funny things happen.”

In her letter, Jennie also wrote about getting eyeglasses for two women, Loh and Hsu.

“They were as excited as two children going to a party. Both came to me and bowed, beaming happily and say, ‘Shih-shih! Shih-shih’ (Thank you). The glasses will be ready Monday and the price is $180,000.00. We are so pleased.”

Inflation was rampant in China throughout the 1930s and ’40s. In November 1947, the New York Times reported that the Chinese dollar had dropped to an all-time low of 104,000 per $1 U.S. So the eyeglasses must have cost around $2 U.S.

Friends and family passed around Jennie’s letters from China. She said they asked that she write one letter to be read at the Ames Women’s Club. The topic: Friendship with China.

“I suppose it is appropriate,” Jennie wrote in response. “I must put my mind on it. There is so much to tell, and I must condense carefully.”

Most of Jennie’s letters are about family, culture, customs and life in China. Only occasionally she mentioned social and economic problems, which were escalating. In this letter, she wrote that she was glad the Chinese government had begun awarding merit-based scholarships.

“We are glad to see in a recent paper that the government has decided on scholarships for worthy students as a substitute for subsidies granted to all students,” she wrote. “It is hoped there will be no more strikes. There are few jobs for college students, who are trained largely for government positions, and not for productive enterprises. That is a change that is greatly needed. But I mustn’t go into that. I don’t like to waste space on paper, but I must stop and get ready for lunch.”

Aug. 18, 1947 – Jennie wrote another letter to Mike, who would become my father many years later. She alternatively referred to him as Mikie and Mikey. Excerpts from her letter:

“Some little boys and girls here go to school now. We see them with their little school bags, and sometimes they read out of their school books as they walk. The books would look funny to you because they do not have any letters, but strange drawings that mean words. They never had to learn to spell, but if they have a good education, they have to learn thousands of words and how to draw them. Then they begin to read at the very back of the book, and they must read the words in lines that go from the top to the bottom of the page, and they begin at the line farthest to the right, and read from right to left.

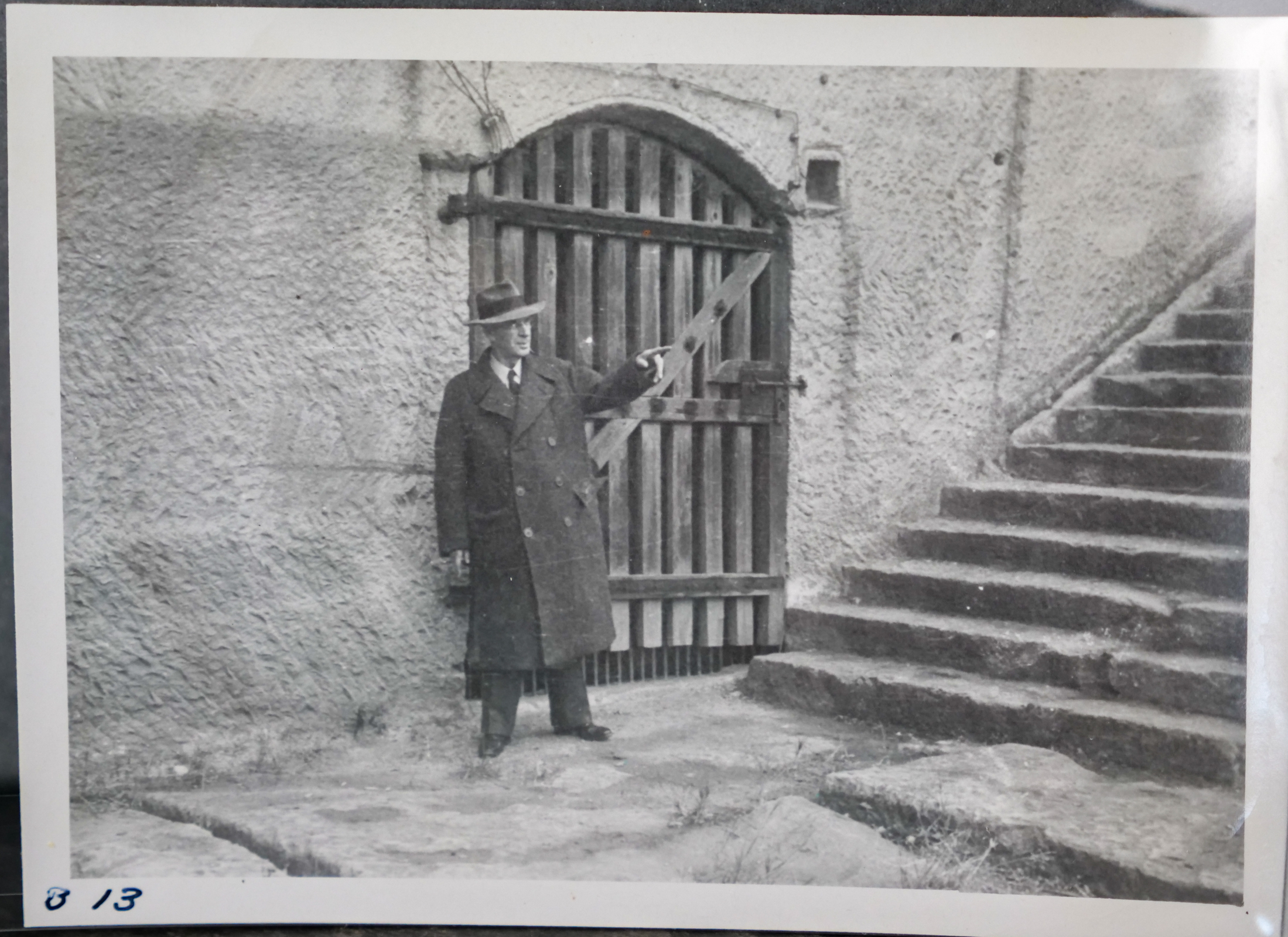

“Right back of one of the buildings where Grandfather works there is a bomb shelter that was used during the war. A very, very poor family lives in it now, and when I walk to the office in the mornings with Grandfather about four little boys come out to meet us every morning. They do not have any clothes on at all, now that it is summer, and they have no hair, but they have sores all over their heads. Their noses are always running, and they couldn’t be any dirtier. Often their mother stands and watches, with one baby in her arms, and one or two a little older beside her. They do not belong here, but there is no place for them to go.

“There are a great many other children near here who are kept as clean as they can be kept, as they live in only one or two rooms, and their clothes are washed in the stream that flows near by. Often the water looks very dirty to us, but they do the best they can. Before it is light we can hear women beating their clothes with sticks on stones to clean them as well as they can. They hardly ever have any soap because it is scarce and it costs too much. After a while these people will have better homes, and they are being built now. But you see they had to come back after everything had been destroyed during the war, and start at the beginning. We have much the best place to live here at the bureau. It was built for us, and was just finished when we came. Many of the things in the house were taken from homes there were demolished by bombs, and they do not always work, but we have the nicest people to do things for us, and they do not let us lack anything. This morning the water pump was not working, and my awah carried three buckets of water upstairs for my bath, and three for Grandfather’s.”

“One day last week we started to Rotary Club dinner in Nanking, because it was Ladies Night, and we were to celebrate the freedom of our neighbor country India, which was to begin next day. We had a new driver, and he did not know the way to the International Club, where we were going. We thought we might know it when we came to it, so we stopped at a place that looked like it, but we found we were mistaken. Soon about 100 Chinese men, women and children were gathered around the fountain where we stopped, all talking Chinese with the driver, but no one could help. After while I could understand someone to say that someone was coming who could ‘talk American,’ so we waited. Sure enough, in about ten minutes, a very fine looking gentleman in fresh white clothes appeared, presented his card, and where do you suppose we were? At the supreme court, and the gentleman was one of the supreme justices. We had a nice little visit, for he had graduated at Harvard in U.S.A., and he told our driver where to go. We got to the dinner in plenty of time, and heard a very fine talk by India’s ambassador to China, and one by the wife of China’s ambassador to India.

“The next evening we went to a dinner at the home of the vice minister of agriculture and forestry in Nanking. The street where his house is is so narrow that people had to crowd against the walls around houses to let the car pass. But when we got to the place at ‘Tiger Bridge’ we went through a wall gate and were in a large court yard. The vice minister hires about twenty-five of his poorer relatives to work for him, and they and their families live inside this wall, too. The vice minister’s young second wife who was born and lived in California all her life before coming here is very unhappy because she is not used to this way of living. Her mother-in-law tells her what to do, and directs the home and the care of the baby. I feel sorry for this young woman, because she wants to feed her baby regularly and carefully, and she can not. The baby has been having convulsions lately.

“If you were here you would see many strange things. This morning when I got up, about six o’clock, two men were plowing in sight of our window, with big water buffaloes. Men and women were going by to market, each carrying two baskets of vegetables in baskets hanging from poles across their shoulders. A man was brushing our lawn with a short stiff broom, because it had been mowed, and, as I said before, women were washing on the stones by the stream.

“Did you ever try to eat with chopsticks? We do often when we are away from home. I do not think it is easy, but it is fun. Every day after our meals are over and the dishes are washed and put away, our servants (six at this house) take a big basket of cooked rice, some bowls of cooked meat, green vegetables, sauce with peppers, or whatever they have, and gather around a box in a shady place in the yard, each one with his or her own bowl and chopsticks to eat with. They never use plates or spoons. What a good time they have eating together! It is their social occasion. One day they fixed a Chinese dinner for us, and gave us their chopsticks to eat with. They assured us they had been washed in boiling water, and I am sure they were. We liked the dinner so much that we asked them to serve one every week, and we bought a set of chopsticks. A set means ten pairs because ten people at a round table is considered right. Often there are more people though, and our table is not round, and we can seat twelve or fourteen people when we have company.”

Nov. 8, 1947 – In a letter to Margaret, Jennie wrote that the American school in Nanjing had a Halloween party. By now, the weather was cooler. “Wonderful,” she called it.

She was astonished that so many Chinese people had given her gifts.

“This giving of gifts seems to be an enjoyable custom with the Chinese. I’m getting so that I do not know what to do about it. I’m about ‘given out.'”

March 1948 – Edwin Hansen, one of the four experts who joined Lee in China, returned to the U.S. because his wife, Dorothy, was ill.

March 28, 1948 – Jennie wrote a letter to her youngest daughter, Ethel, then 39, asking what she thought about a gift she bought for her son, Bob, then 12.

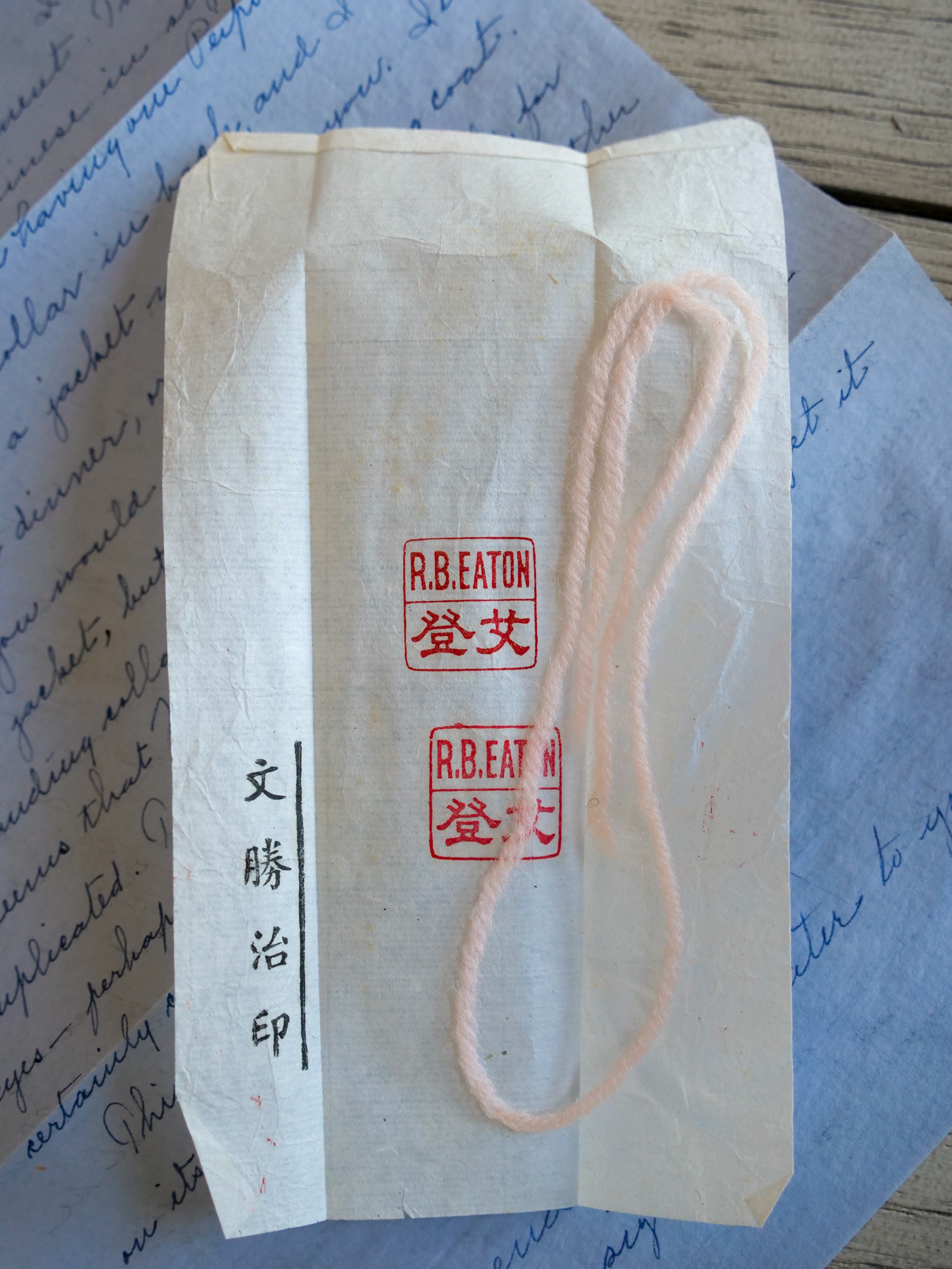

“I have gotten an Ivory ‘chop’ for Bob, and now I am wondering. I’ve told you it is hard to find things for children. I thought a piece of ivory would be something to keep always, and maybe he would get a kick out of stamping his name, in English and in Chinese. But maybe I should have had just English. Everyone in China uses a chop for a signature. This one is a piece of ivory about 2 ½ inches long and as big around as the enclosed print. Robert Chien helped make his Chinese name. Now if I get one for Michael, should it be like Bob’s or should it have just his English name, M.D. Eaton? I don’t know about getting this into U.S.A. Ivory is expensive, and sold by weight so you can’t de-value it much. You might inquire at the post office. I’d like Bob’s to be for his birthday.

“I have some pieces of metal used for money over a thousand years ago, and I want to send them but if they care about them they really ought to have a drawer or someplace to keep such things. What do you think?”

Jennie briefly discussed politics back home, where Harry Truman was running for re-election.

“It seems that U.S.A. affairs are becoming very complicated,” she wrote. “Truman’s speech is opening everyone’s eyes – perhaps it is a good thing. World affairs are certainly chaotic.”

April 19, 1948 – Jennie wrote a long letter addressed to her children and grandchildren. “One couldn’t ask for more beautiful weather than we’ve been having. The willows outside the window where I write hang gracefully and are reflected in the still water in the stream underneath. The red-buds have faded, and the leaves are coming out, and many of the earliest flowers are gone, but others have taken their places, and our flower beds just now are gaudy with marigolds and daisies. A few snap-dragons are showing color, and before long my California poppies that came from seed Margaret sent, will be budding. I’m so pleased with them.”

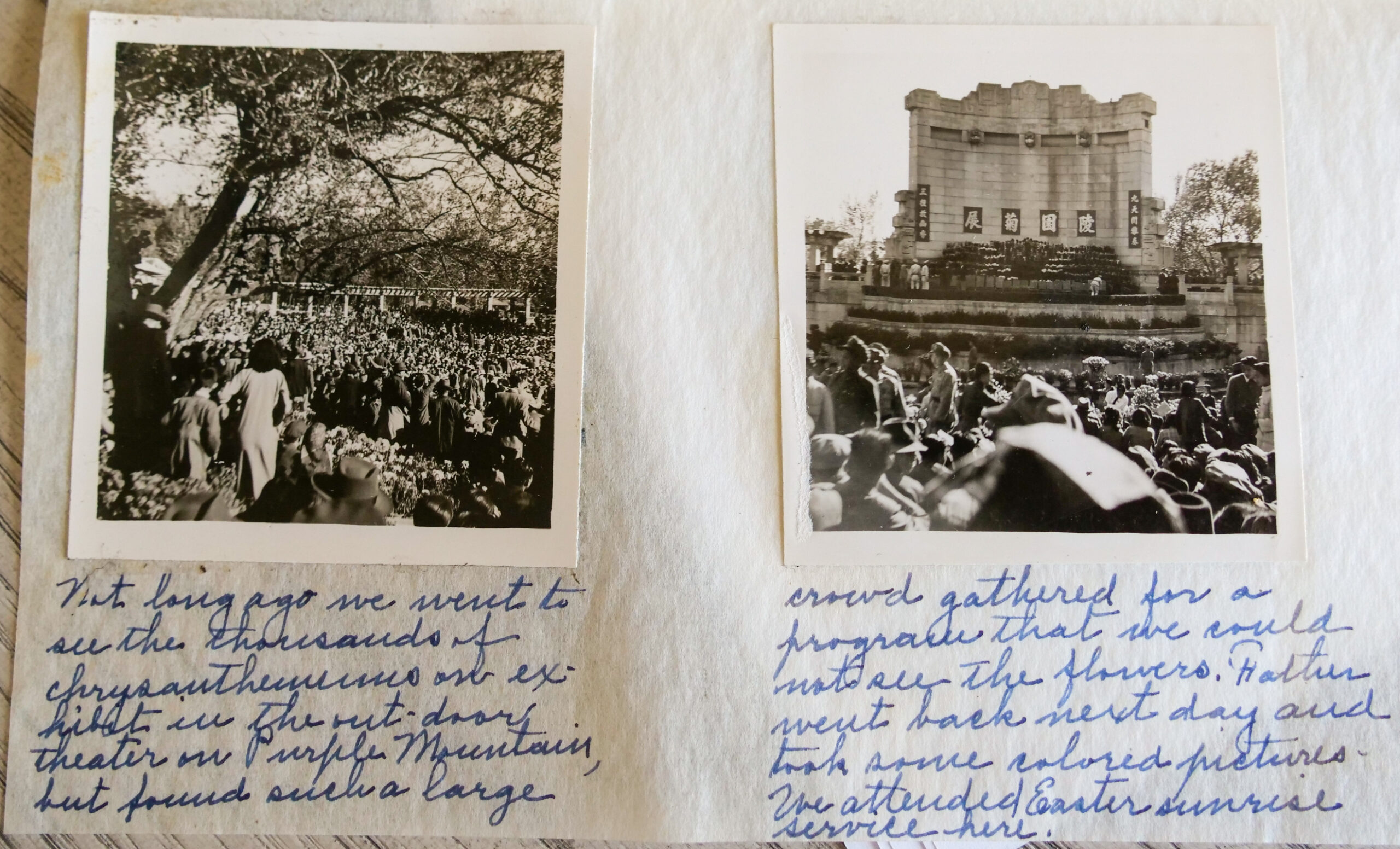

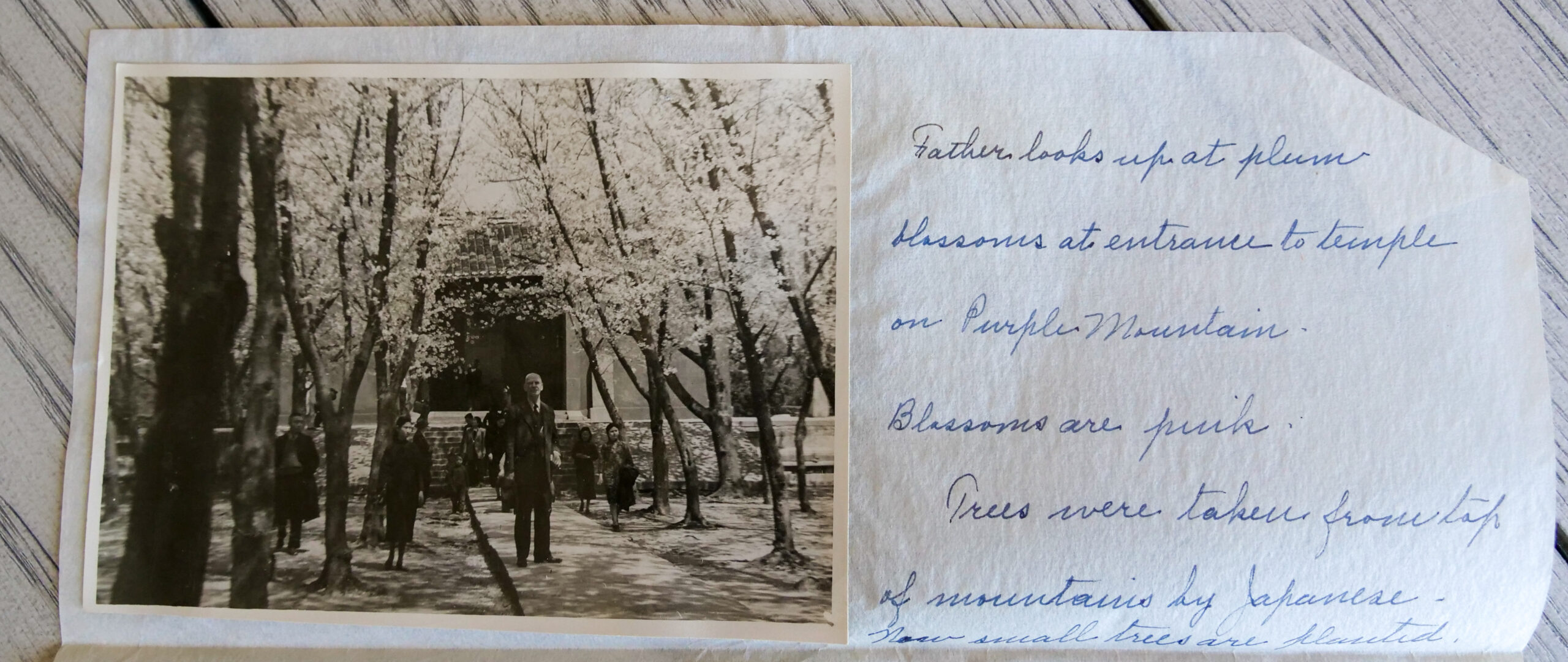

“Yesterday morning quite early we drove over to Purple Mountain and left the car near the pagoda we can see from here and climbed toward the top. The first half-hour was hard climbing, then we came to a fine, smooth path with a gradual grade, and it was wonderful. We looked down on Sun Yat Sen’s tomb, on pagodas, temples and on Nanking, and the view was marvelous. We stopped a while at a look-out, beside a building that had been bombed by the Japanese – and then it was time to come back and have dinner. Next time we must start before seven, and go all the way. On the way down to the car we stopped to see the tree peonies inside a temple wall, just in their prime of beauty.

“At the regular time we went to church – 4:30, and a friend there told us that she had seen Col. Morrill Marston Jr. who sent his regards to us and was trying to get in touch with us. We are trying to get in touch with him too, because last week someone at the ministry called Father and said Col. Marston had inquired about us, and then Father tried to call him, but first he was in conference with the General, and afterward his line was busy. We only have access to the telephone at the administration building, and calling is not too easy. But I’m sure we’ll make it this week. In fact we have learned that he is stationed not far inside the wall as we drive into Nanking and we’ll stop and call. He is Dean Marston’s grandson, and must be the son of Brig. Gen. (or probably General by now) Morrill Marston, whom we knew as a young fellow when we first went to Ames. His grandfather told him about us. The friend at church says he is young, and his wife is to have a baby before long.”

Brig. Gen. Morrill Watson Marston was born in Ames, Iowa, and served in the military during World War I. His father was Anson Marston, dean of the Engineering Division at Iowa State College from 1904 to 1932. His grandson, Col. Morrill Elwood Marston, went to West Point and was later assistant chief of staff for military intelligence for the Hawaiian Department. That’s who was trying to track down Jennie and Lee. Jennie’s letter doesn’t say what he may have wanted. I have wondered what contacts Lee may have had with U.S. officials. I haven’t found many details in the archives. I haven’t discovered any evidence showing that Lee was anything but a college professor. He was invited to July 4 celebrations at the U.S. Embassy in Nanjing in 1947 and 1948, but I don’t know that he had any unusual contact with military, intelligence or political officials.

Jennie told of going to dinner at the home of “Dr. and Mrs. Thompson of the Chemistry Department of Nanking University.” I believe she was referring to James Claude Thomson (Thompson appears to be incorrect spelling), who died in 1974, and his wife Margaret. Jennie wrote that they had been in China for about 35 years. For a time, their next-door neighbor was famed author Pearl Buck.

Jennie said the Thomsons told her that their house was once occupied by Japanese.

“The house had just been restored after the Japanese occupation, and the book shelves across one end of the large living room were only half filled, because the books that had been carried away and hidden had not all been brought back.”

On another occasion, she wrote, Chinese communists took over the house.

“The lives of the Thompson family had been saved only by the fact that some of Dr. T’s graduate students came and stood between them and the attacking army, while their servants helped them escape. Three hundred Chinese had slept in the house at that time. We felt as though we had been living in a dream after spending the evening there,” she wrote.

That episode occurred around the time of what Jennie described as the “Nanking Incident… which I do not remember.”

A Wikipedia entry about the 1927 “incident” states: “Foreign warships bombarded the city to defend foreign residents against rioting and looting.”

Jennie’s letter continued:

“Most of the older Chinese people we know can tell of experiences during the last war that nearly make our hair stand on end.”

Jennie wrote often about her “awah.” I haven’t found a translation for that word, but have the impression she’s writing about her servant.

“One Saturday morning not long ago,” she continued, “there was a sound of excitement and jubilee in the kitchen, and soon Awah came in with a dish holding one dozen red, hard-boiled eggs. It was an announcement that her son, who is a cook for the Richardsons, had a new little daughter. There is one little boy five years old. We joined in the rejoicing, and when we said we would take some of the eggs to Stone’s, another dozen appeared for them. McCollys had a dozen and the servants had all they could eat. We learned that the proper acknowledgement was a gift of money wrapped in red paper, so I tied up several hundred thousand dollars using red ribbon and two of my little red bells that give so much delight, and sent the package over. I’ve seen the baby and she is darling. She was wearing a little stocking cap knit out of some red yard I had given Awah. All tiny babies wear stocking caps, it seems.”

Jennie enjoyed sightseeing near her home.

“The day after Easter was a holiday here, and we had James take us over to Purple Mountain to see the flowering plums, cherries, peaches and apricots in bloom. These trees bear no fruit, but their beauty is beyond description. They are all pink, from pale to deep red, some trees having several shades of color.”

In this letter, Jennie said U.S. Ambassador Stuart had hosted her and other Rotarians at his home. She also wrote about what she described as Milton Reynold’s “wild stunt.”

Reynolds was an American entrepreneur who produced a popular ballpoint pen that used metal beads used in bomb sights and barrels, according to Wikipedia. He met with Chinese scientists in Nanjing before suddenly leaving the country in secret.

Reynolds left behind a trove of ballpoint pens, Jennie wrote.

“Rotary had gotten enough of them so that each one at this final dinner was given one as a favor. I think they will be collector’s items sometime, when that foolish story is told.”

Jennie wrote about hosting a dinner party for Dr. P. W. Tsou. He had persuaded Iowa State College to sponsor Chinese students. He had been to Ames twice, and he was Lee’s most important liaison in China.

Jennie wanted the dinner party to go perfectly. Two cooks, both freshly shaved, were busy in the kitchen getting ready for their distinguished visitor. One cook cleaned chickens while the other polished silver.

“I knew everything would be all right,” Jennie wrote. “And everything was all right till dinner was ready and we were waiting for the last four guests when we suddenly found out the door into the kitchen could not be opened. It was not locked but one part of the mechanism was hold it.”

Food and servants were on one side of the door, hungry guests on the other.

“Finally Father came around to the dining room side and, taking careful aim, he directed a kick, a hard one, beside the knob and the door burst open, exposing what seemed to me to be a sea of anxious faces on the kitchen side. A little piece of metal had fallen against the latch and Father’s kick broke it. Just then the last guests arrived, and all went well, but I couldn’t help wondering what would have happened if the door had been stuck after the meal had started.”

Later in the letter, Jennie raved about her Chinese cook.

“Cook was making doughnuts and sent me two hot sugary ones to eat. No one ever made better doughnuts, either,” she wrote. “When I took my plate to the kitchen Cook was lifting doughnuts in and out of fat, and rolling them in sugar with chopsticks. He makes mayonnaise and stirs gravy that way, too.”

In a postscript to the letter, Jennie wrote that she just learned that Dorothy Parker died.

“I must add a sad note this evening… Mrs. Hansen died yesterday, the 19th. I have been anxious since learning her white corpuscles were too low, and she was having blood transfusions. I went to Nanking this afternoon to tell university and church friends.”

May 8, 1948, – In a letter to Ethel, Jennie told of a Chinese officer who befriended her.

“I was interrupted yesterday by a young man of the Military Police who wants to be my son, and for me to be his mother. He is lonesome. I had asked him for Chinese dinner at twelve o’clock, with Robert Chen to help us talk, and he came at 10:30. I will tell more about this amusing yet pathetic incident in a joint letter.

“Robert Chen is the finest young man we have around here. He hopes to be admitted to a college in U.S.A., preferably I.S.C. (Iowa State College), and if he gets to go, he wants to see Robert Eaton and all of you. I hope Bob will not mind my calling him “Robert” some of the time – I like the name so much.”

Robert Eaton was Ethel’s son. His younger brother Mike was tall for his age. Jennie wrote:

“I’m a little worried about Michael. I am sure he will be all right, if you are patient with him. He has grown much too fast you know, and was advanced in school beyond his years. I was startled to see how thin his face looked in his pictures. He will not be like Bob, but there will be things that he can do better, when he gets his bearings. Father says not to let him get an inferiority complex by comparing him with Bob, who has so many triumphs, and make him feel appreciated for the things he does well. I’m a little homesick for him.”

Jennie also wrote about P.E.O., founded in Iowa in 1869. She and many of my relatives are members of the group, “a sisterhood based on the principles of friendship and loyalty.”

Jennie wrote:

“I am a little sorry you are P.E.O. president but I expect you couldn’t help it.”

Jennie, who suffered from pernicious anemia for much of her life and lost siblings to the disorder, also stressed the importance of staying healthy.

“It is so important that you keep well while the children are growing up. My great regret about my younger years us that I was ill so much when your children were young. Now-a-days we could do more about it….”

Jennie also passed along some grandmotherly advice: “I’ll repeat my little lecture about being systematic, and teaching the children to be, because there is so much less worry and fuss if work, habits and money spending are done by a schedule. How about the boys’ accounts? Does Sister sew like you used to at five?”

Before closing, Jennie reflected on her future.

“I begin to think about the home we will have after we go back. I wonder where we will live. I suppose for a while in Ames, but I’d like to be in a place with a climate that does not have such extremes. I’d like a nice small house with a nice view. I’ve wondered sometimes about some Colorado town, near enough to Denver so the children could visit us. Well, I have no idea how things will work out. This is one of the days when my writing is very poor. Much love – Mother.”

Aug. 12, 1948 – In a letter to Margaret, Jennie said she sometimes longed for more privacy.

“We are having a very wonderful and unusual time. The only thing we would both wish for is that there might have been some place where we could have gone for quiet and rest alone together. We have all lived in such close proximity together since leaving San Francisco… But we have gotten along famously together – it is just that every family needs to be along some.”

Leaving China

By November 1948, Ambassador Stuart predicted the fall of Nanjing. In a telegram, he wrote:

“Government deteriorating rapidly and Communist occupation Nanking–Shanghai area expected near future. Generalissimo apparently determined attempt defense Nanking but has insufficient forces avert its loss and will probably be forced flee to some other point in China. On these conditions orderly transfer power to successor government highly unlikely. Orderly transfer possible if Generalissimo removed or left office in favor temporary caretaker government but we have no firm reason anticipate such development.

“We believe only sporadic unorganized resistance to Communist will prevail after fall capital. Communists will have military capability move armies virtually any point in country without significant resistance. Flight or disintegration present Government will probably result in high incidence civil unrest and breakdown law and order throughout country with hazards to personal safety American and other foreign nationals.”

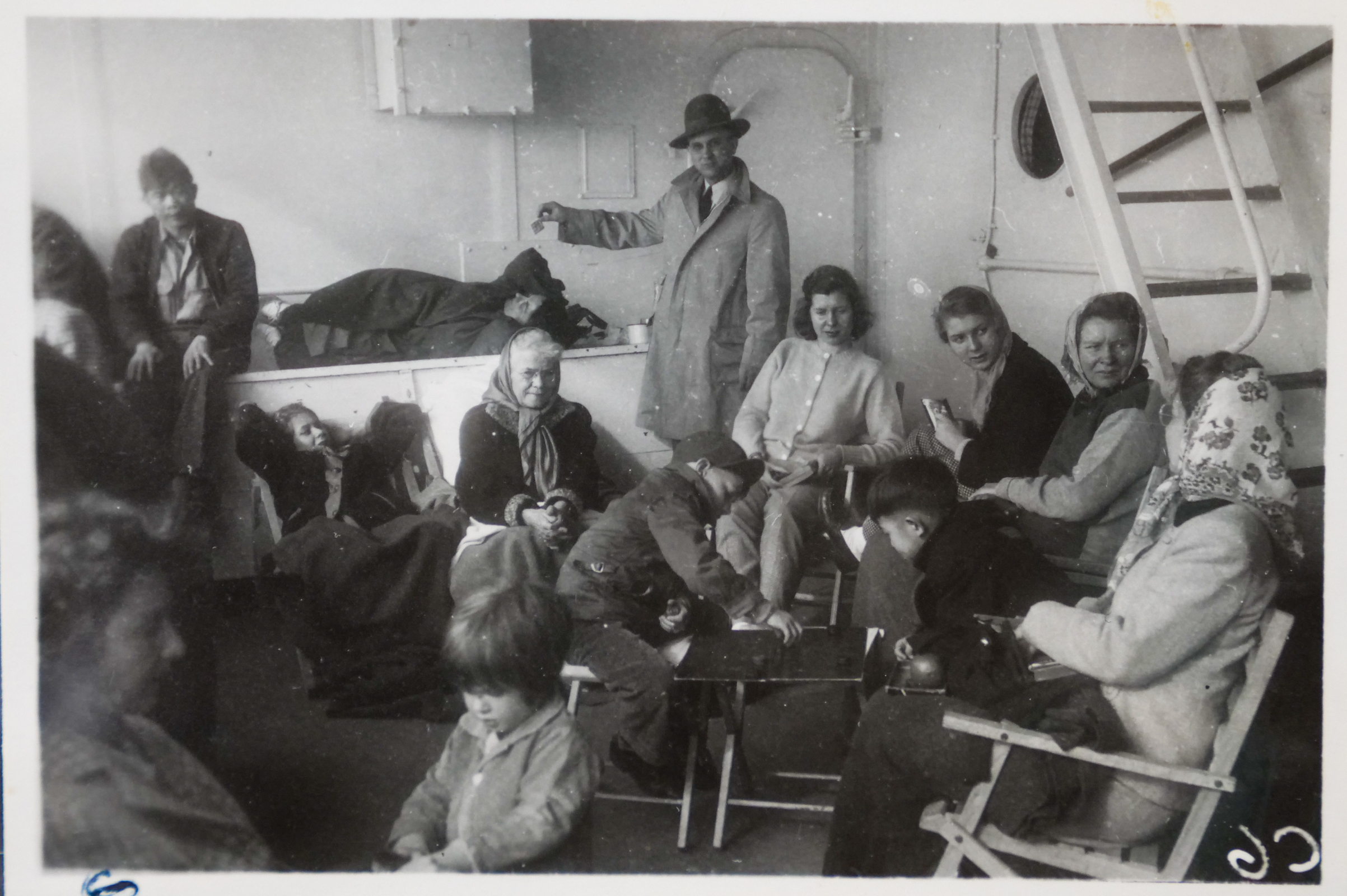

On Nov. 15, Jennie and Lee were evacuated from Nanjing to Shanghai aboard the USS Horace A. Bass high-speed transport ship. Jennie wrote:

“After a hectic time getting away from Nanking, with fire crackers popping in our yard, and many friends going to the boat with us, it was a never-to-be forgotten experience to find U.S. navy boys meeting our cars and taking over our baggage, and helping us onto the boat, where we were registered for evacuation, and showing us to our places.

“It is crowded, but we each have a bunk and one bag with us, the other bags being in the hold. Our trunks and boxes are on a S.S.M. We brought food and bedding but we do not need it here for the navy provided blankets and good food. We don’t know where we will be in Shanghai or how long we will stay there. If we go home the long way it may take two or three months. It is quite an experience. A week ago Sunday yesterday, we were all at church, many of us knowing we were leaving soon and last night we met again on this boat some who thought they would stay a while longer, some men who were going to Shanghai to see their families off for U.S.A. We were very sad to leave Nanking but are thrilled with the U.S.N. Life magazine photographer has been taking pictures – mostly of mothers and children. Maybe you will see some of them. There is much to tell but it will have to wait.”

Jennie was grateful for Chinese friends who helped them get out of China safely. She wrote:

Jennie was grateful for Chinese friends who helped them get out of China safely. She wrote:

“Our Chinese friends were very anxious to have us go for they wanted to leave themselves but would not until they knew we were safely out.”

According to an April 9, 1949, article in the Ames Daily, Lee and Jennie left Shanghai aboard the Flying Arrow freighter on Dec. 6, 1948.

The freighter went through India, Japan, Philippines and Egypt, making 21 stops. Jennie wrote that she and Lee could have gotten home sooner, but would have had to leave their belongings in China. They reached New York on March 20, 1949.

Aftermath

Once back home, Lee told the Ames Daily newspaper that he hoped the Chinese would continue improving agricultural production despite the change in government.

As part of the China program that Lee managed, International Harvester funded the agricultural engineering training of 20 Chinese students. That was the first phase of the program.

Chinese agriculturalist P.W. Tsou had proposed the idea to International Harvester in 1945. The U.S.-trained engineers “became the first generation of agricultural engineers in the People’s Republic of China,” according to Ruisheng Shang, who has written about U.S.-China cooperation in agriculture. See “From rural reconstruction to agricultural engineering: a study of the cooperation between the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and the International Harvester Company (1945-8)”.

Lee told the Ames Daily, “Working at the bureau are 20 young Chinese men who were all trained in this country, and we feel that they will have the inspiration to add the impetus needed for success. Any prospects of raising Chinese standards of living must start on the farms. Eighty percent of the population is engaged in farming, and that is why the status of the agricultural population is so determinant a factor in the country’s economy.”

While looking through university and family archives, I didn’t find much more that would reveal Lee’s thoughts about China and the program he led. I don’t have any information about his political views.

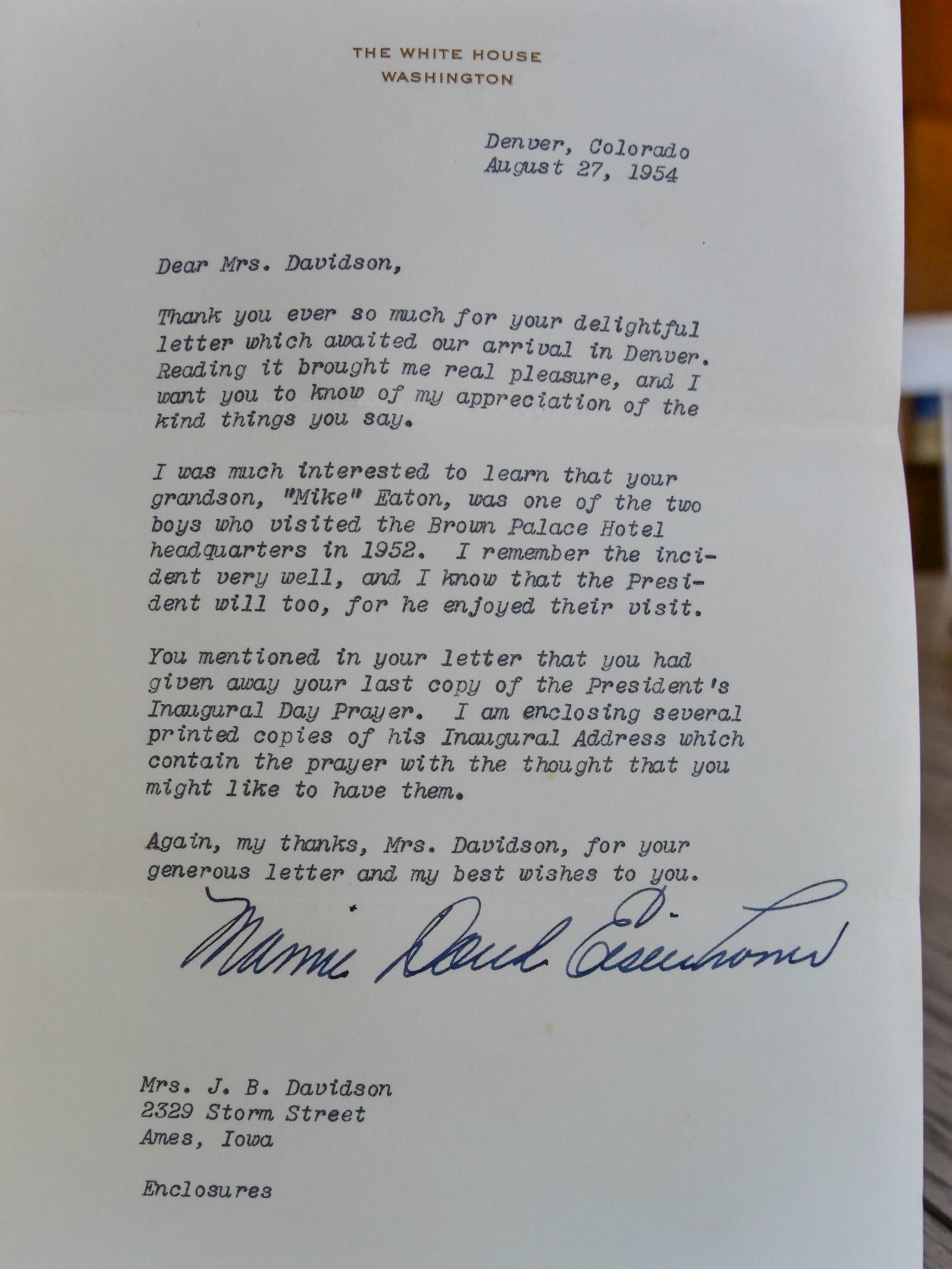

Jennie did not say much about her political views, either, although I found clues that she liked Dwight Eisenhower, president from 1953 to 1961. It turns out that Jennie’s grandson Mike was one of two boys who visited the Brown Palace Hotel in Denver while it was Eisenhower’s campaign headquarters. First Lady Mamie Doud Eisenhower wrote to Jennie to thank her on Aug. 27, 1952.

“Thank you ever so much for your delightful letter which awaited our arrival in Denver,” Eisenhower wrote. “Reading it brought me real pleasure, and I want you to know of my appreciation of the kind things you say.

“I was very much interested to learn that your grandson, ‘Mike’ Eaton, was one of the two boys who visited the Brown Palace Hotel headquarters in 1952. I remember the incident very well, and I know that the President will too, for he enjoyed their visit.”

Eisenhower included copies of the president’s Inaugural Day Prayer because Jennie had told her she had given away her last copy of it.

Archives contain notes from a tribute called “This is Your Life” that was given in honor of Jennie in the 1950s. The tribute mentions her experiences in China.

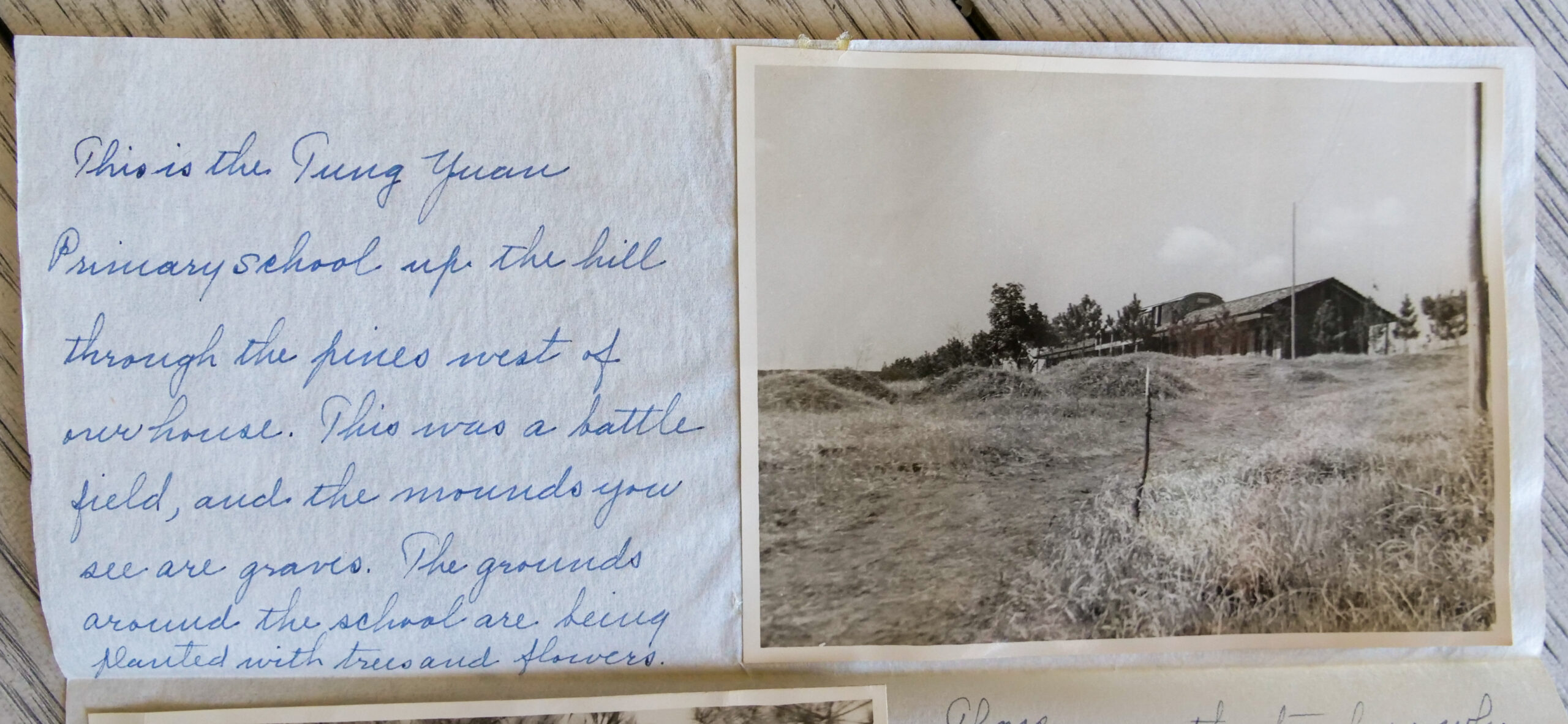

“…When you moved in you saw a great deal of ruin all about you – former Chinese agricultural staff members were living in hen-houses or just about anything until Quonset huts could be built.

“You were greatly impressed by the most courteous way in which the Chinese people from all walks of life treated you. While in China you did a variety of things from attending a number of receptions for high officials to raising some silkworms; you learned a bit of the Chinese language and became adept at bargaining with the Chinese shopkeepers.”

Esther McColly, who lived in the same house as the Davidsons in China, wrote in a letter presented at the tribute: “If all our representatives to foreign countries were such as the Davidsons how fortunate we would be. Their influence, kind deeds and way of life were felt everywhere.”

The tribute said Jennie bought eyeglasses for a maid, and a sewing machine for “house boy.”

She also taught English classes in China, and bought books and supplies for a school.

“Then on a Wednesday in November, after you had lived in China for nearly two years, you returned to your home following a day’s visit to a silk factory in Nanking and found a message from the American ambassador awaiting you. This message informed you that because of Communist advancements it was no longer safe for you to remain in Nanking.

“A boat would be ready Sunday to take you to Shanghai. Then followed three busy days in which you packed your possessions, bade farewell to your Chinese friends, left your home which was just becoming beautiful with blossoming flowers, and boarded a Navy destroyer. Although the journey was tense and at all times the boat’s guns were manned in case trouble should arise, you reached Shanghai unmolested.”

Nanjing was the capital of China from 1912 to 1949. The People’s Liberation Army captured the city on April 23, 1949. Chinese nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek retreated to Taiwan. Mao Zedong announced the creation of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1, 1949, in Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

Nanjing was the capital of China from 1912 to 1949. The People’s Liberation Army captured the city on April 23, 1949. Chinese nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek retreated to Taiwan. Mao Zedong announced the creation of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1, 1949, in Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

My great-grandfather died on May 8, 1957, two years before I was born. He was 77. Jennie died on May 31, 1965, in Denver at the age of 82.

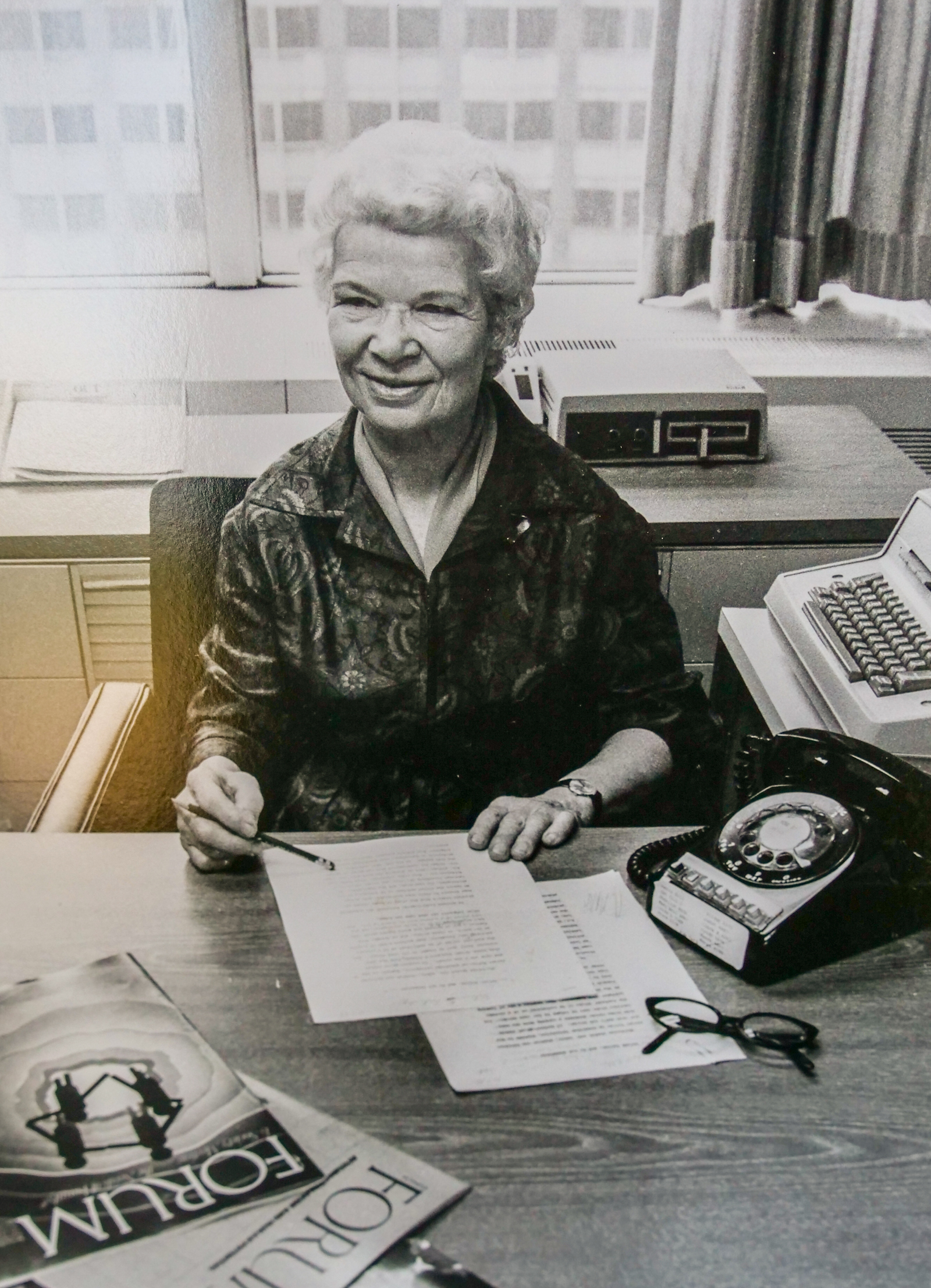

Their daughter, Margaret, graduated from Iowa State University and made her way to New York, eventually working as an editor at Ladies Home Journal in New York. That got me thinking that journalism might be a great path to follow.

Members of the Davidson family are buried on the campus of Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa.