I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Feb. 28, 1999.

This tiny Huichol village, with its primitive mud and stone huts, sits on a ledge overlooking a breathtaking rock-walled canyon in the state of Jalisco. It’s rugged terrain, an area Philip True once called “John Huston country: a 100-mile swath of big-boned mountains and rolling mesas .” And trekking alone through this land with his backpack, tent and dog-eared copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood was the lanky Texas journalist’s dream.

Mr. True, 50, the Mexico City bureau chief of the San Antonio Express-News , wanted to find out how the region’s long-isolated Huichol Indians were coping with the onslaught of civilization. He hoped to witness the clash of old ways and modern times.

But as one colleague grimly put it, “He was the clash.”

Mr. True’s battered corpse was found buried in a shallow grave near this Huichol village on Dec. 16, triggering a murder investigation full of intrigue, controversy and contradictions.

“It’s such a confounding case,” said Emma Lew, a Dade County, Fla., coroner brought in by the FBI at the request of the Mexican government to witness a second autopsy of Mr. True. “The more you hear about it, the more perplexing it gets.”

Two Huichol Indians – Juan Chivarra, 28, and Miguel Hernandez, 24 – were charged with murder in the case. They are awaiting trial and face up to 30 years in prison. Police are convinced they acted alone and say they consider the case closed. But for Mr. True’s friends and colleagues, the strange saga is far from over.

Troubling questions about the murder remain, they say. The government’s version of what happened only scratches the surface, and some of the culprits may be roaming free.

U.S. officials have no authority to investigate but say they are keenly interested in learning the truth. And editors at the Express-News say they plan to continue digging into the case.

Still, conceded Mr. True’s boss, Fred Bonavita, “We may never know the truth: how and why Philip was killed. It may forever remain a mystery.”

“No permission’

In the back-country village near where Mr. True’s body was found, many of the Indians are unapologetic.

“He had no permission to be here,” said villager Martin Chivarra, a brother of one of the suspects. “It’s like me going to the United States without a passport. “La migra’ [U.S. immigration agents] catch you. They abuse you; they mistreat you. Here, it’s the same.”

The “passport” Mr. True needed to journey through Huichol territory was permission from tribal elders. Without that, some Indians probably thought no one knew he was traveling in the area and decided it was safe to attack him, said Carlos Chavez, director of the Jalisco Association for the Support of Indigenous Groups in Guadalajara.

No doubt, the killers never imagined Mr. True’s disappearance would bring in such a furious swarm of soldiers, police and journalists, all wondering what happened to Mr. True.

No doubt, the killers never imagined Mr. True’s disappearance would bring in such a furious swarm of soldiers, police and journalists, all wondering what happened to Mr. True.

“If a Mexican had been killed,” Mr. Chavez said, “the government wouldn’t have lifted a finger.”

Leaders of the Huichols say they’re just anxious to see the mystery solved.

“People are getting the wrong idea. They think we’re all violent,” said Jesus Lara, president of the Union of Huichol Indian Communities of Jalisco. “But it’s not true. We have welcomed many strangers into our villages, and nothing has happened. We feel deep shame over the murder. Now we only want justice. So if these two Huichol suspects are guilty, they should be punished.”

Other Huichols politely suggest that Mr. True was “crazy” to try to walk alone through 100 miles of treacherous terrain, with unforgiving peaks as high as 8,989 feet.

“It’s easy to get lost. Or you can fall and get hurt,” said Rito Gonzalez, 46, a slender Huichol campesino who led two journalists through the remote territory where the murder occurred.

Other barriers

Aside from the physical rigors, travelers going through Huichol country face language, racial and cultural barriers.

“You have to put it in perspective,” said Susana Eger Valadez, who runs the Huichol Center for Cultural Survival and Traditional Arts in Jalisco. “Huichol Indians may have battery-powered radios, they may wear Western clothes and Nike tennis shoes, but they’re living in the past, in a different century.

“I’ve gone into remote villages before, and when people first see me, they run and hide. Or the kids rub my skin to see if the white comes off. Some of these Indians have never seen white people before,” said Ms. Valadez, who has lived among the Huichols for 22 years.

That the natives would treat an outsider with animosity is normal, said Stacy Schaeffer, an anthropologist and Huichol expert at the University of Texas-Pan American in Edinburg, Texas.

“Huichols, especially when they drink, often show a real hostile attitude toward foreigners,” she said. “They sometimes kick foreigners out of their communities or throw them in jail. Inequality is at the heart of a lot of it. The foreigners have money, they have all these fancy gadgets, cameras and sleeping bags. But many don’t have a clue about Huichol culture. And they don’t give anything to the community. It’s just take, take, take.”

Mr. True was sensitive to Huichol ways, said his widow, Martha, who is awaiting the birth of their first child, to be named after his father.

“He loved the Huichols so much,” she said. “He had studied them and visited them on and off for 15 years.”

And indeed, the Trues’ cozy Mexico City home was decorated with portraits of the Indians and pieces of their artwork, from bead-covered masks to colorful wall hangings.

Romantic vision

Still, some say Mr. True’s vision of the Huichols was so romantic that it might have blinded him to some of the harsh realities in their communities. Their villages, he once wrote, were “marked by the nearly constant sound of children laughing and playing.”

The Huichols, descendants of the Aztecs, number about 50,000 and are one of 56 indigenous groups in Mexico. They lived in relative isolation for more than 1,000 years. Even after the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century, they kept many of their customs and religious ways, including pilgrimages to harvest peyote, a coveted hallucinogen.

In 1972, the first roads began reaching the outer limits of their territory, stretching from Jalisco into the neighboring states of Nayarit, Zacatecas and Durango. Outside influences continued to grow, and by the 1990s, drug traffickers were demanding that the Indians grow marijuana crops for them, the Huichols say.

“These traffickers are untouchable,” grumbled Maurilio de la Cruz Avila, a leader in the Huichol town of San Sebastian. “They’ve got ranches. They’ve got houses in Guadalajara and Mexico City. And they pay the police and military to protect them.

Indian rights advocates estimate that marijuana growers, cattle ranchers and timber cutters have illegally taken nearly 200,000 acres of Huichol territory.

“It hurts us,” said Mr. de la Cruz, who met recently with Jalisco state officials to try to reclaim some of the stolen property. “For us, the land is our sacred mother. We don’t betray it, sell it or give it away.”

Suing the invaders

Mr. Chavez, the Indian advocate, has helped the Huichols file more than 150 lawsuits against the land invaders. In apparent retaliation, someone recently kidnapped his son, who escaped only after the pickup carrying him crashed.

Mr. Chavez has relocated his family and continues to aid the Indians, but he said he steers clear of traffickers.

“Doing what I’m doing is dangerous enough, and it alone could get me killed,” Mr. Chavez said. “We’re not the FBI.”

It was into this rugged, sometimes perilous land that Mr. True set off on Nov. 28, hoping to return home by Dec. 9.

Huichols and others who have retraced his steps say the journalist got off a bus in Tuxpan de Bolanos, northwest of Guadalajara, bought a small bottle of tequila and began his hike.

A few of the journalist’s Indian friends in Tuxpan say they find it strange he didn’t stop to visit them or say hello. He was carrying a gift for one of them, 74-year-old medicine man Jesus Gonzalez, but never delivered it. He simply disappeared down the trail.

Some theories

Some villagers theorize Mr. True might have run into trouble from the beginning. Others think he simply craved solitude, saying he skirted several settlements, walking and camping alone.

Eventually he reached Yoata, home to 24 people, most related by blood or marriage.

The village has no electricity, no TVs and no running water. It is accessible by foot, horse or mule and is a grueling trek from the nearest dirt road. Mr. True was the first gringo to visit, residents say.

The Huichols and authorities have given conflicting versions of what happened after Mr. True’s arrival. Investigators say Juan Chivarra told them “the devil took hold” of him, and he killed the reporter on Dec. 6.

The second suspect, Mr. Hernandez, later contradicted that version, telling Mexican reporters that it was he who murdered Mr. True on Dec. 4 after the reporter allegedly barged into his house, kicked him and scared his wife.

Both suspects, now in jail in Colotlan, north of Guadalajara, have again changed their stories.

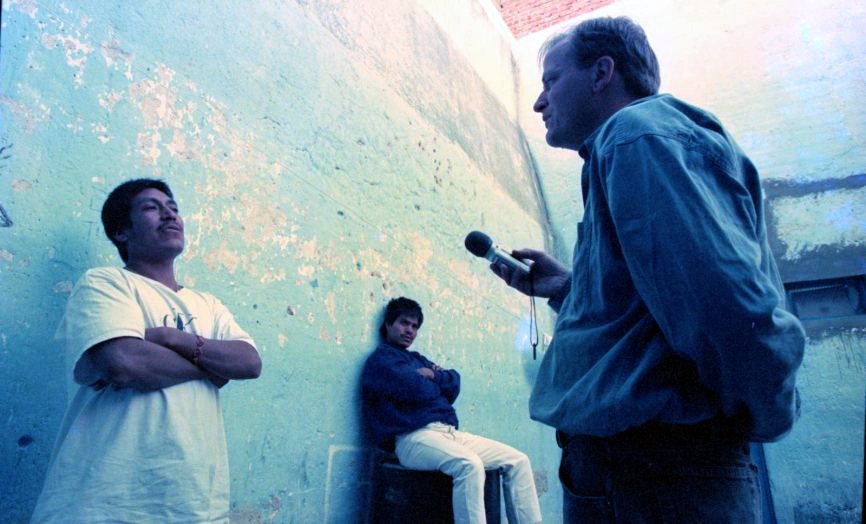

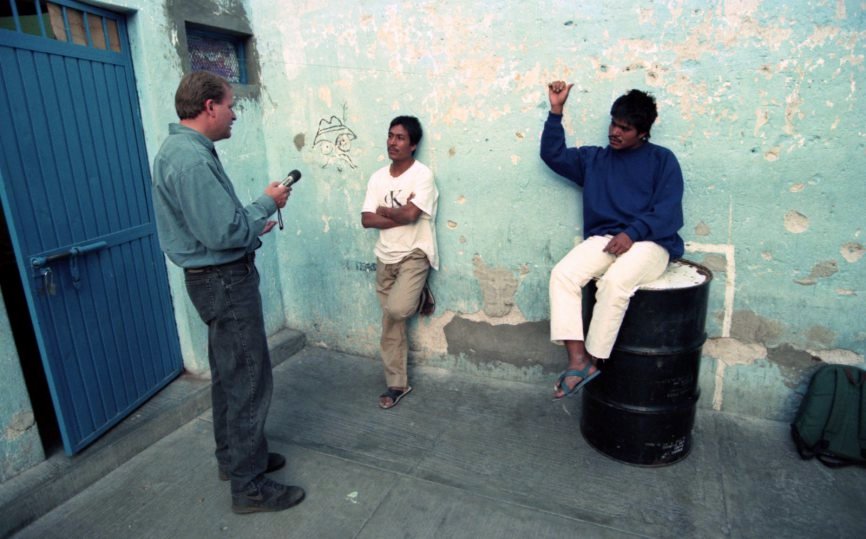

In an interview, Mr. Chivarra said he was vaccinating cattle when Mr. True appeared, asking for directions to another village.

“I was coming down a trail when I saw him. He was on a mule trail, not an Indian trail. He said he liked walking there,” Mr. Chivarra said. “I got scared. He was carrying a big backpack. I thought he was probably going to kill me.”

Mr. Chivarra said the reporter went on his way, and that was the last he saw of him.

Mr. Chivarra said the reporter went on his way, and that was the last he saw of him.

“I didn’t kill him,” said the suspect, denying that he ever confessed. “I want to leave this jail.”

Mr. Hernandez sat nearby, atop a barrel, glancing around nervously, wringing his sweat-drenched palms. Asked about his purported confession, he stared at the ground, finally mumbling a few words: “I don’t remember anything.”

Human rights activists and Indian advocates who have interviewed the two believe Mr. Chivarra may be the killer but is trying to pin the crime on his shy brother-in-law.

“We think Juan has Miguel under some kind of psychological control, some kind of pressure,” said Samuel Salvador, a respected Huichol lawyer and adviser to the Indians. “Maybe he’s threatened him or his family.”

Mr. Chivarra denies that and says his big worry is being sent to the United States for allegedly killing an American.

“Some people tell me I could get 80 years in prison. Or maybe even put to death,” he said.

Some villagers who know Mr. Chivarra say they are afraid of him and his family.

“They’re trouble. We all know it,” one man said.

Another man disputed that, calling Mr. Chivarra “good people.”

Joel Simon, director of the Americas program for the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York, said he has asked Mexican authorities to release more information about the case in order to erase questions about the investigation.

He and others have nagging doubts about the case:

If the Huichols were so afraid of Mr. True, why send just two people to attack him? Were others involved?

Why did Mr. True have so much alcohol in his system – 0.26, more than three times the legal limit? His friends say he was a light drinker who rarely touched hard liquor. Even the suspects say they did not think he was drunk.

Why would he get drunk with such a brutal hike ahead? Did someone force liquor down his throat?

Why kill him in the first place? If the motive was to rob him, as some think, why not take his watch and rings?

Why wasn’t his reporter’s notebook recovered? And what else is missing? Mr. True, an avid photographer, was carrying a new Canon camera, but police say he shot less than a roll of film – odd, given the breathtaking scenery.

Authorities say they recovered only what was in the camera plus nine unused rolls. Were there any others? If so, what happened to them? And why were some of the developed photos dated Dec. 7, at least a day after the Huichols claim they killed him?

Martha True said she’s grown weary trying to find answers.

“For a while I tried to play Sherlock Holmes,” she said. “But it drove me nuts. I think it’s going to be hard to ever discover the truth.”

Some people believe traffickers or drug-corrupted soldiers may have played a role in the killing. Marijuana can be found in the region during the rainy summer months, and many Huichols suspect smugglers may be to blame.

Back in Yoata, Martin Chivarra, the suspect’s 19-year-old brother, called the drug accusations “big lies.”

Sitting outside on a sunny morning, the teenager wove thin strands of decorative twine into the edges of a leather belt.

Chickens, turkeys and dogs scampered in the dust nearby while young Indian mothers sat on the ground nursing their infants.

“We’re not bad people,” he said. “We’re Huichols. And we want people to leave us alone.”