I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on May 19, 2003.

Cuba’s beleaguered dissidents began to stir this spring, and authorities crushed them. When their wives began silent protests, the government threatened to throw them in prison, too.

No wonder the wives gather each Sunday to pray to Santa Rita, patron saint of desperate, seemingly lost causes.

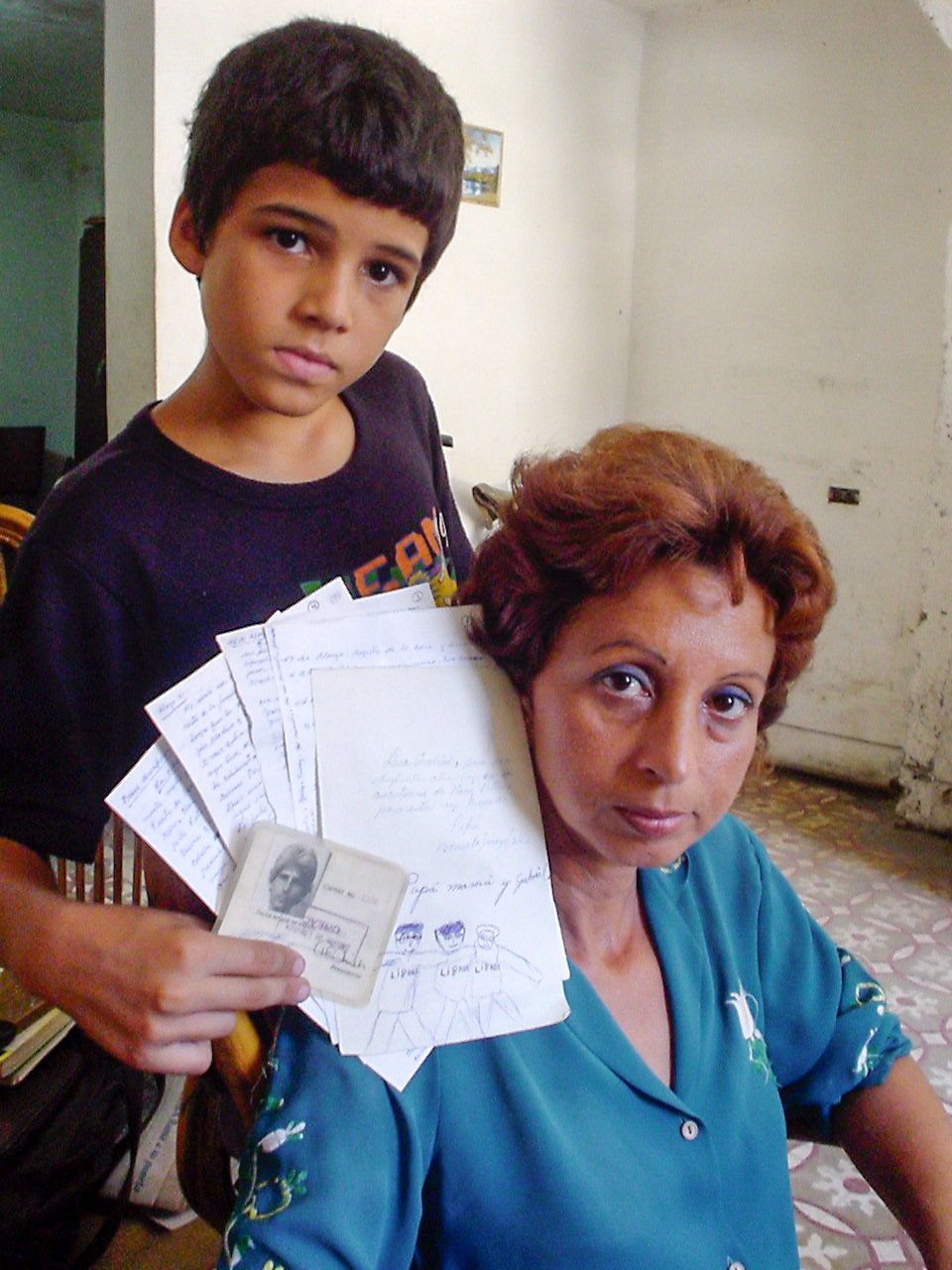

“We’re not the ones who are in jail, but we’re suffering, too,” said Yolanda Huerga, wife of Manuel Vázquez, a Havana journalist who was sentenced to 18 years in prison last month. “The authorities harass us constantly.”

The lives of dissidents and their families have become ever more precarious in the wake of a government crackdown on the political opposition in March. Authorities again showed they are in firm control, and dissidents again say democracy seems like a far-off dream.

But the government’s harsh treatment of its critics has had an unexpected side effect: Some dissidents’ relatives – housewives and others with no political leanings and no history of government opposition – have become pro-democracy activists.

But the government’s harsh treatment of its critics has had an unexpected side effect: Some dissidents’ relatives – housewives and others with no political leanings and no history of government opposition – have become pro-democracy activists.

With little fanfare, a few of the wives began praying for their husbands’ release at Santa Rita church three years ago. They formed a small committee, which suddenly grew to more than two dozen members last month after authorities sentenced 75 dissidents, journalists, librarians and others to up to 28 years in prison on charges of trying to undermine the government.

“In the beginning there were only a couple of us. Now the wives’ committee has grown, and we’ve become a problem for the government,” said Laura Pollán, 55, whose husband, Hector Maseda, received a 20-year sentence.

The wives usually dress in white with black scarves for the 10:30 a.m. Mass. On some Sundays, they walked in protest along Fifth Avenue in Havana. They didn’t carry signs, and they didn’t talk. They just walked quietly for a few blocks before returning to the church and making their way home.

Dissent sets of alarms

In many countries, such low-key demonstrations would be permitted. But in Cuba, where even the hint of dissent is taboo, they set off alarms.

State security agents in past weeks called or met with many of the wives, ordering them not to march, the women say. Prison visits for some of them have been canceled. Others were threatened with prison terms of their own for up to 20 years.

“We’re just going to go home today. We’re not going to march,” one woman explained after Mass on Sunday. “We don’t want a confrontation.”

Cuban officials have been unapologetic about targeting dissidents, accusing them of being paid agents of the United States.

American officials deny paying the dissidents but say they will continue to supply them with books, tape recorders, cameras and other resources to help them bring about a peaceful transition to democracy in Cuba, a communist nation run by Fidel Castro since 1959.

Dissidents say their movement has grown dramatically since the early 1990s.

Hiding out of fear

Ms. Huerga, a housewife, said she begged her husband not to join the political opposition in 1989. When Mr. Vázquez did anyway, she said, “It was like a bomb falling on my face. It was horrible. I hid under the bed for the first year and didn’t want to come out of the house.”

State security agents put her husband under surveillance, she said. They routinely took him in for questioning. They threatened him. And sometimes they knocked on the door at 4 a.m. to harass the family, she said.

Now that Mr. Vázquez is in jail, Ms. Huerga said, she remains “very afraid ” – but determined.

Now that Mr. Vázquez is in jail, Ms. Huerga said, she remains “very afraid ” – but determined.

Authorities “can scare us,” she said. “But they can’t fight against love. How could they possibly rip Manuel out of my heart? They can’t.”

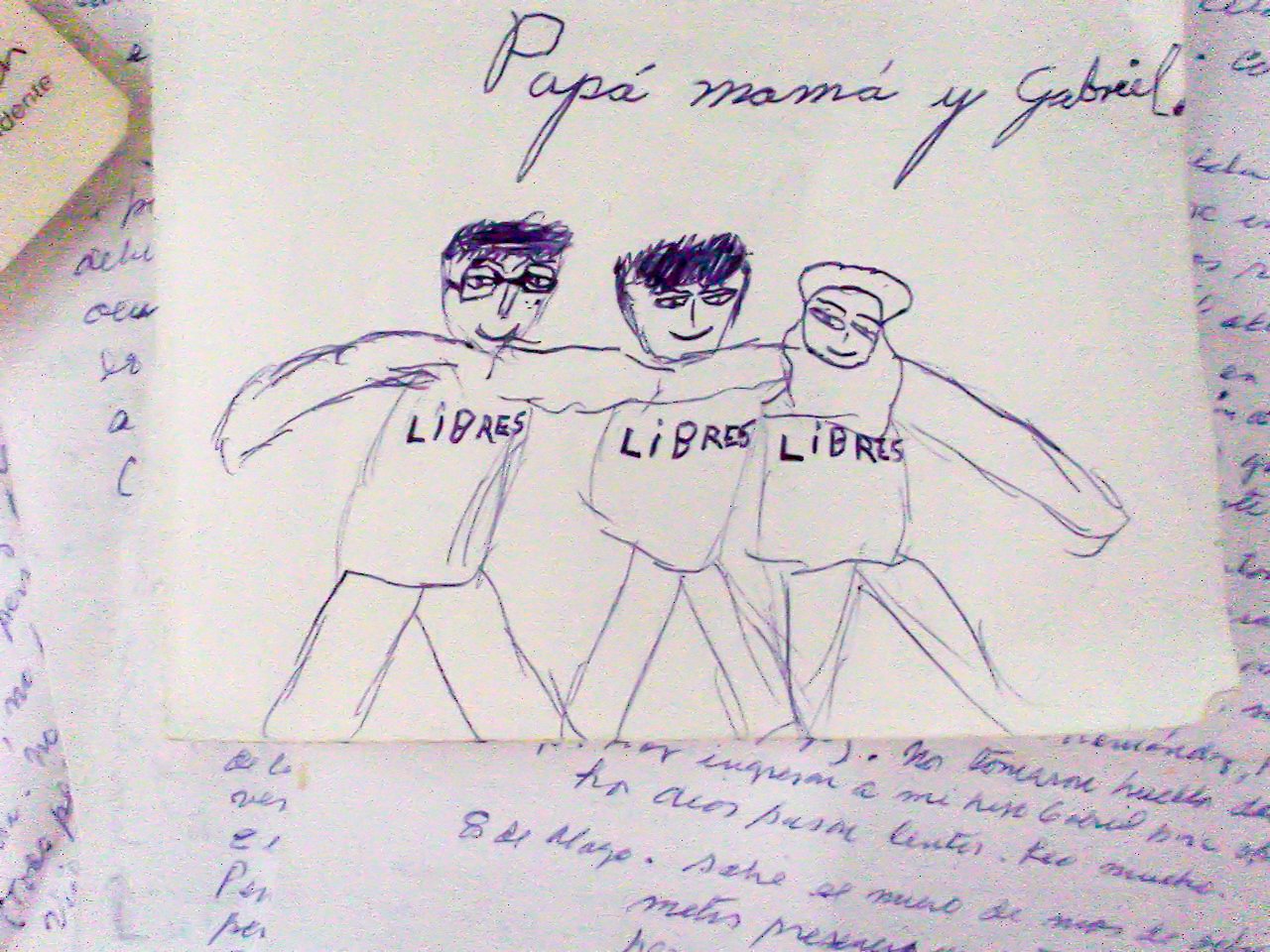

She said their 9-year-old son, Gabriel, “constantly asks about his dad and when he’s going to return. He doesn’t understand that he could be gone for a long time.”

Some schoolchildren tell Gabriel that his father is “a mercenary, a traitor,” Ms. Huerga said, but she tells him not to believe it.

“He’s brave,” she said. “He dared to challenge a government.”

While the dissidents were on trial in March, Ms. Huerga said, authorities visited her son’s school to try to find out whether he was developing anti-government views.

“But he doesn’t know anything about that,” she said. “He just wants his father back.”

She and the other wives say they hope international pressure will help speed their loved ones’ release. They know it’s an uphill fight.

“The government has a lot of power,” said Ana Aguililla, whose husband, Francisco Chaviano, 50, is serving a 15-year term. “Our only hope is to pray. There’s no other hope at the moment.”

Fittingly, the wives turn to Santa Rita de Casia, an Italian nun who lived from 1386 to 1457. As the story goes, the saint bled for 15 years from a chronic wound caused by a crown of thorns.

“Santa Rita is our lawyer – our lawyer for impossible causes,” Ms. Aguililla said.