I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Oct. 12, 1996.

MEXICO CITY – Like some illustrious head of state, Amado Carrillo Fuentes has loyal, heavily armed guards who would, and sometimes do, die for him in a flash. He uses ultra-sophisticated communications equipment, and he sends advance teams wherever he goes.

But Mr. Carrillo is neither politician nor statesman. He’s a drug baron, one of the most powerful smugglers Mexico has ever seen, U.S. law enforcement authorities say. And his sprawling operation is flooding Texas and the Southwest with cocaine, methamphetamines and heroin, U.S. drug agents say. The drugs “are pouring in. They’re falling out of the sky,” said a U.S. law enforcement official based in Texas. “It’s like we took a half dose of antibiotics and . . . the disease is back with a vengeance.”

Among the recent seizures were 2,232 pounds of cocaine found last month at a home along Pelhem Road in El Paso. The white powder was in heat-sealed packages apparently designed to throw off cocaine-sniffing dogs, say agents with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

U.S. authorities decline to say whether the drugs can be traced to Mr. Carrillo, but they suspect he is one of the leading suppliers of illicit narcotics to Texas. And catching him won’t be easy, they say, despite unprecedented cooperation between U.S. and Mexican law enforcement agencies.

Unlike some of Mexico’s cocaine cowboys, who flaunt their wealth and carouse in public with their numerous girlfriends and mistresses, Mr. Carrillo is discreet. He’s a businessman who patterns his operation after the Cali gang in Colombia.

The Carrillo organization has traditionally controlled Ojinaga on the Texas border; Ciudad Juarez, across the border from El Paso; and parts of Durango, Sinaloa and Sonora states, U.S. agents say.

The Carrillo organization has traditionally controlled Ojinaga on the Texas border; Ciudad Juarez, across the border from El Paso; and parts of Durango, Sinaloa and Sonora states, U.S. agents say.

His organization is made up of loosely connected clandestine cells, U.S. agents say. Each cell specializes in a certain task – ranging from unloading drugs to transporting them – and the dismantling of a cell has little impact on the overall operation, they say.

Another factor in Mr. Carrillo’s favor is that he prefers to work with other Mexican traffickers rather than try to kill them off.

“Amado has tried to be the peacemaker,” said a high-level U.S. law enforcement official. “He has influence. I think his value is that he’s more like the Cali people. He tries to keep the heat away and not provoke acts of violence.”

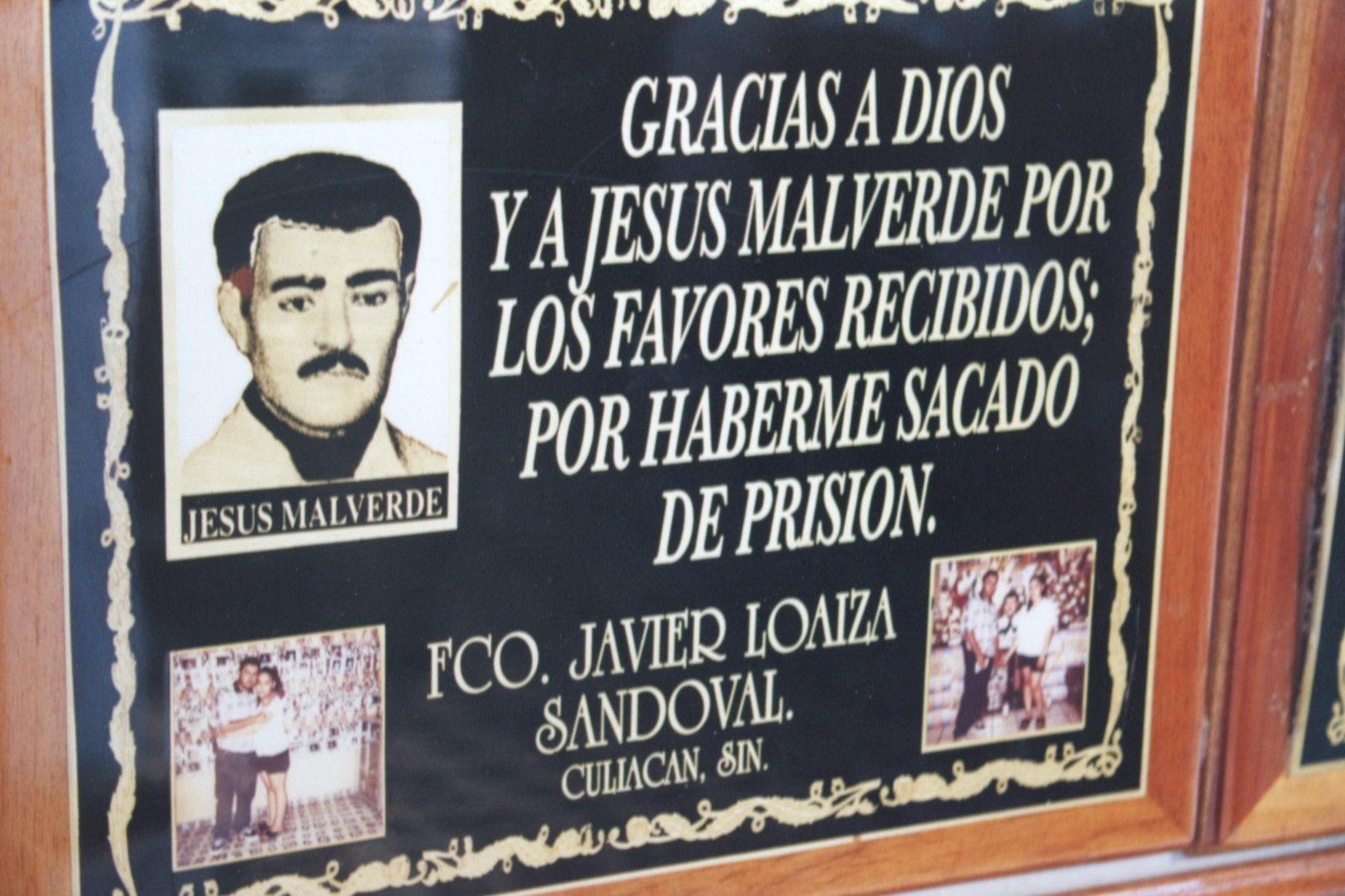

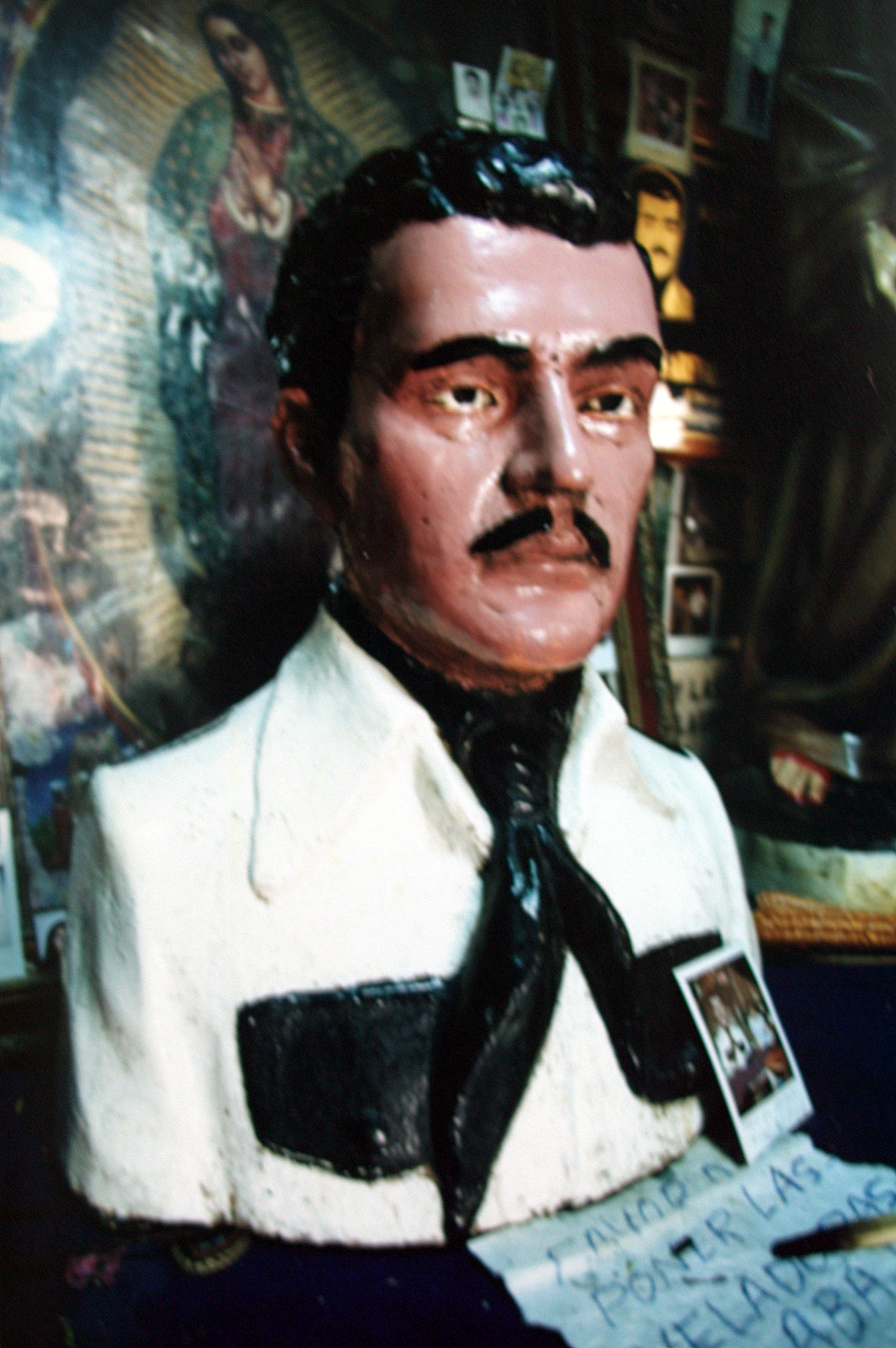

Mr. Carrillo’s seemingly benign nature has prompted some Mexicans to characterize him as a sort of Robin Hood. They compare him to Chucho El Roto, a bandit who roamed the Mexican countryside in the early 1900s, robbing the rich and turning over some of the proceeds to the poor.

People like Mr. Carrillo “because he does favors. He pays for funerals, loans money. He helps people,” a resident of rural Sinaloa state told Mexico City’s Reforma newspaper.

U.S. officials say no matter what kind of favorable publicity Mr. Carrillo receives, no one can head a major drug gang without resorting to murder.

“Just because someone may have the image of a country-club trafficker and not a barrio switchblade smuggler, it’s still just a facade,” said a U.S. official who studies Mexican drug issues. “These are not Robin Hoods who regularly build churches and baseball stadiums. These are dysfunctional individuals.”

Mr. Carrillo’s underlings are believed to be responsible for dozens of murders in Ciudad Juarez. The victims are usually found gagged and bound, with telltale bullet wounds in the head. Mexican officials concede that the vast majority of the murders remain unsolved. U.S. officials complain most cases aren’t even investigated.

A key obstacle is corruption, U.S. and Mexican agents say. Mr. Carrillo is thought to have several hundred former and current officers and officials on his payroll, the Americans say.

His gang has so successfully penetrated law enforcement agencies in Ciudad Juarez that the Mexican government last year decided to send in the military. But that experiment ended earlier this year with the Carrillo organization intact.

To many, Mr. Carrillo and other top Mexican and Colombian traffickers seem untouchable, and the fallout from that doesn’t end in Mexico, U.S. officials say.

“When a state trooper on the eastern shore of Maryland gets shot and killed by two crack peddlers traveling south out of New York City, I see Amado Carrillo Fuentes in that. I see Colombian trafficker Pacho Herrera. They play a role in the death of this trooper,” said Thomas Constantine, DEA administrator. “They’re the major profiteers.”

Mr. Carrillo has been indicted on drug trafficking charges in both Dallas and Miami, although in Mexico he’s only wanted on minor weapons violations.

He was born in the state of Sinaloa in the 1950s; his exact age is unknown, but he’s likely to be in his mid-40s. He’s believed to be 6 feet tall and weigh 185 pounds. He has green eyes and brown hair, although some say he sometimes bleaches it blond.

He uses a number of aliases. And there have been scattered reports that he’s had plastic surgery to change his appearance.

Before he became a big-time trafficker, Mr. Carrillo applied for and obtained a U.S. border crossing card in 1985 in Texas.

His gang’s smuggling potential became clear on Sept. 28, 1989, when U.S. authorities discovered 21.3 tons of Carrillo cocaine and more than $12 million in cash in a warehouse near Los Angeles. The drugs – worth several billion dollars on the street – marked the largest cocaine seizure in American history.

His gang’s smuggling potential became clear on Sept. 28, 1989, when U.S. authorities discovered 21.3 tons of Carrillo cocaine and more than $12 million in cash in a warehouse near Los Angeles. The drugs – worth several billion dollars on the street – marked the largest cocaine seizure in American history.

Mr. Carrillo is alleged to have gotten his start in trafficking with the help of his uncle, Ernesto Rafael Fonseca Carrillo.

Mr. Fonseca was a founding father of Mexico’s cocaine trade, U.S. authorities say. His career flourished in Sinaloa, Sonora and Baja California states until he was arrested and charged in connection with the 1985 murder of DEA Special Agent Enrique Camarena.

With his uncle’s blessing, young Amado became an apprentice of notorious trafficker Pablo Acosta, who operated in Ojinaga, Mexico, across the border from Presidio, Texas, agents say..

Mexican authorities say Mr. Acosta was killed in a shootout with police in April 1987. U.S. law enforcement officials say there may have been more to it: As one account goes, Mr. Carrillo paid a corrupt Mexican police commander $1 million to kill his mentor.

Whatever the case, Mr. Carrillo continued his rise, taking advantage of a power vacuum that occurred after the then-premier drug patron, Miguel Felix Gallardo, was arrested in connection with the Camarena murder in 1989, U.S. agents say.

Mr. Carrillo soon earned the nickname Lord of the Heavens, reportedly for his knack of handling huge loads of cocaine flown from Colombia aboard Boeing 727s and other passenger jets.

Hit men tried to kill Mr. Carrillo on Nov. 24, 1993, in Mexico City. They stormed into the Bali Hai restaurant and sprayed the place with machine gun fire. Five people were killed, including three of Mr. Carrillo’s bodyguards, a police officer and an architect who was dining at the restaurant. Mr. Carrillo and his family escaped. Three of his bodyguards were arrested in the shooting’s aftermath; a judge released two of them a few weeks later despite police warnings that they were dangerous individuals.

Some analysts have blamed the assassination attempt on Colombian traffickers angry because more than nine tons of their cocaine had been seized off Mexico’s Pacific coast in August 1993.

But others say the Tijuana-based Arellano Felix gang may have been responsible. As that theory goes, the Arellanos were upset because Mr. Carrillo had fronted several hundred thousand dollars to one of the Arellanos’ most bitter enemies, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman. The loan was reportedly for a load of weapons sold by a corrupt Mexican government arms broker.

During the summer of 1995, the Carrillo gang suffered another blow. Colombian police arrested Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, head of the Cali cartel and a key cocaine supplier for the Carrillo organization.

Colombian authorities announced they had destroyed the cartel, but U.S. officials claim that Cali gang members have been arranging drug deals from prison.

“They’re operating with a little less efficiency. But they haven’t stopped,” a senior law enforcement official said.

Mexican Attorney General Antonio Lozano Gracia has pledged to clamp down on drug trafficking and related corruption. And since taking office in December 1994, he has fired more than 1,200 police officers, about a third of the federal force. He says a full clean-up may take 15 years.

U.S. law enforcement officials give him high marks and say he faces many exceedingly difficult challenges.

“Lozano’s going to get slapped with criticism no matter what when the fact is the corruption may be three, four, five, six levels below him,” said one U.S. official who requested anonymity.

Many Mexican officials are tired of U.S. criticism of their anti-drug efforts. President Ernesto Zedillo said there would be no trafficking problem in Mexico if it weren’t for the millions of American drug users.

“The Mexican people recognize themselves as victims and never as beneficiaries of the illicit trafficking of narcotics,” he said in a recent speech.

Still, some former U.S. drug agents complain that progress in the search for the Lord of the Heavens and other major traffickers seems painfully slow.

“Mexico hasn’t kept its end of the bargain,” said Phil Jordan, former head of the El Paso Intelligence Center, jointly run by the DEA, FBI and other agencies. “Where is Amado Carrillo Fuentes right now? Doing business as usual.

“There are a lot of mountains that have to be climbed.”