I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Dec. 4, 1996.

MEDELLIN, Colombia – The former murder capital of the Western Hemisphere is turning over a new leaf – and it’s not a coca leaf, either.

Ex-hit men are casting aside their Uzis and taking guitar lessons, social workers say. Gang members are rubbing elbows with shrinks at group therapy sessions. And police once loyal to ruthless drug traffickers are wiping out illicit crops with a vengeance. A city that used to be dominated by killings, savage violence and a ruthless cocaine baron named Pablo Escobar is undergoing a remarkable rebirth. Crime and social unrest remain sobering problems, but the murder rate has plunged and city leaders vow to make Medellin as squeaky clean as Disneyland.

“What we’ve gone through has been difficult. But with Escobar gone it’s like the city is catching its second wind,” Mayor Sergio Naranjo said. “People are losing their fear. People feel a sense of progress. We now look at the future as an opportunity.”

Until his death three years ago, Mr. Escobar, head of the Medellin cartel, waged a campaign of terror and bombings against Colombian police, politicians, soldiers, judges and journalists. U.S. drug agents say his organization smuggled hundreds of tons of cocaine to the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before Colombian police killed him in a rooftop shootout on Dec. 2, 1993.

Now Medellin’s leaders say it’s time to forget the bloody Escobar reign. And as part of the healing process, they’re launching a worldwide campaign next year to promote the city as an oasis of theme parks and family entertainment.

Water park and trains

A huge $35 million water park just opened along the banks of the Medellin River. It features wave pools, 12 water slides, a re-creation of a stretch of the Amazon River and computer-enhanced images of jungle creatures. Other multimillion-dollar projects – including a children’s museum and a convention center – are planned.

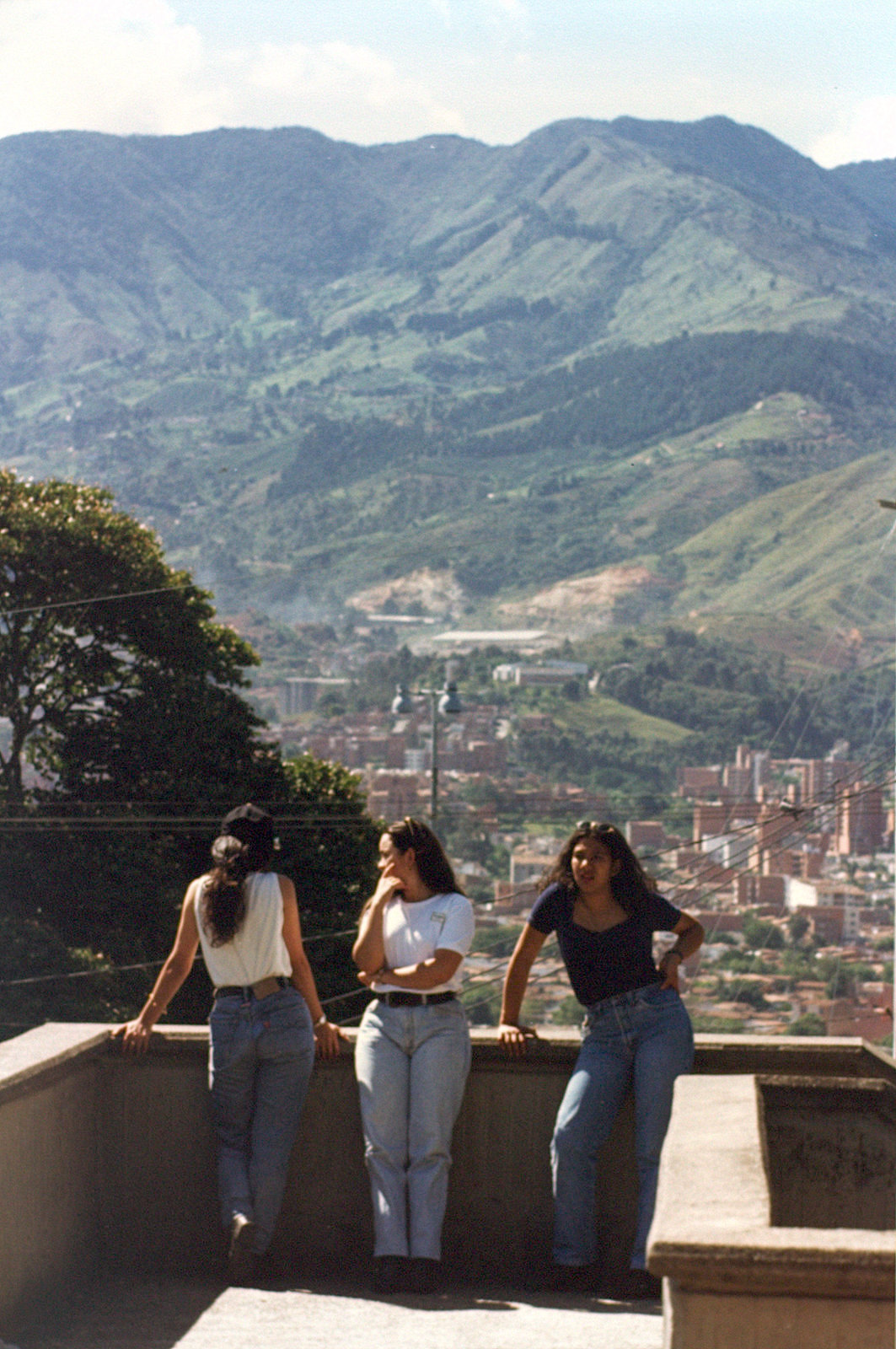

Already, Medellin, nestled in a lush valley, boasts seven five-star hotels, a state-of-the-art sports complex, botanical gardens and a gleaming urban railway system, the first in Colombia.

“We have the most modern metro in the entire world,” Mr. Naranjo said. “People here are proud of it. They take care of it as if it were their own mother.”

As he sees it, Medellin’s notoriety has made the city of 1.8 million people known throughout the world. All that needs to be done now, he says, is to capitalize on that name recognition, using it to promote the town’s pluses.

So next year city leaders will begin passing out 5,000 promotional kits on Medellin at Colombian embassies around the globe. They also will tout the city on an Internet home page. Their main target: American, European and other investors willing to sink big bucks into the region, helping to build dams and highways, and to boost local industries, from flower and banana farms to textile plants and shoe factories.

“People are going to have to start taking notice of Medellin because in 10 years it will surely be one of Latin America’s most developed, best-planned cities,” said Mr. Naranjo, 52, former head of a professional soccer team.

Poverty runs deep

Not everyone is convinced that the city is assured peace and prosperity. Many living in poor neighborhoods blanketing the hills on the city’s edge are worried.

“There have been many changes, but to me they haven’t been that great or meaningful,” said Alberto Preciado, 23, a university student who works with troubled teenagers. “The image of Medellin that some people want to project doesn’t always match reality.”

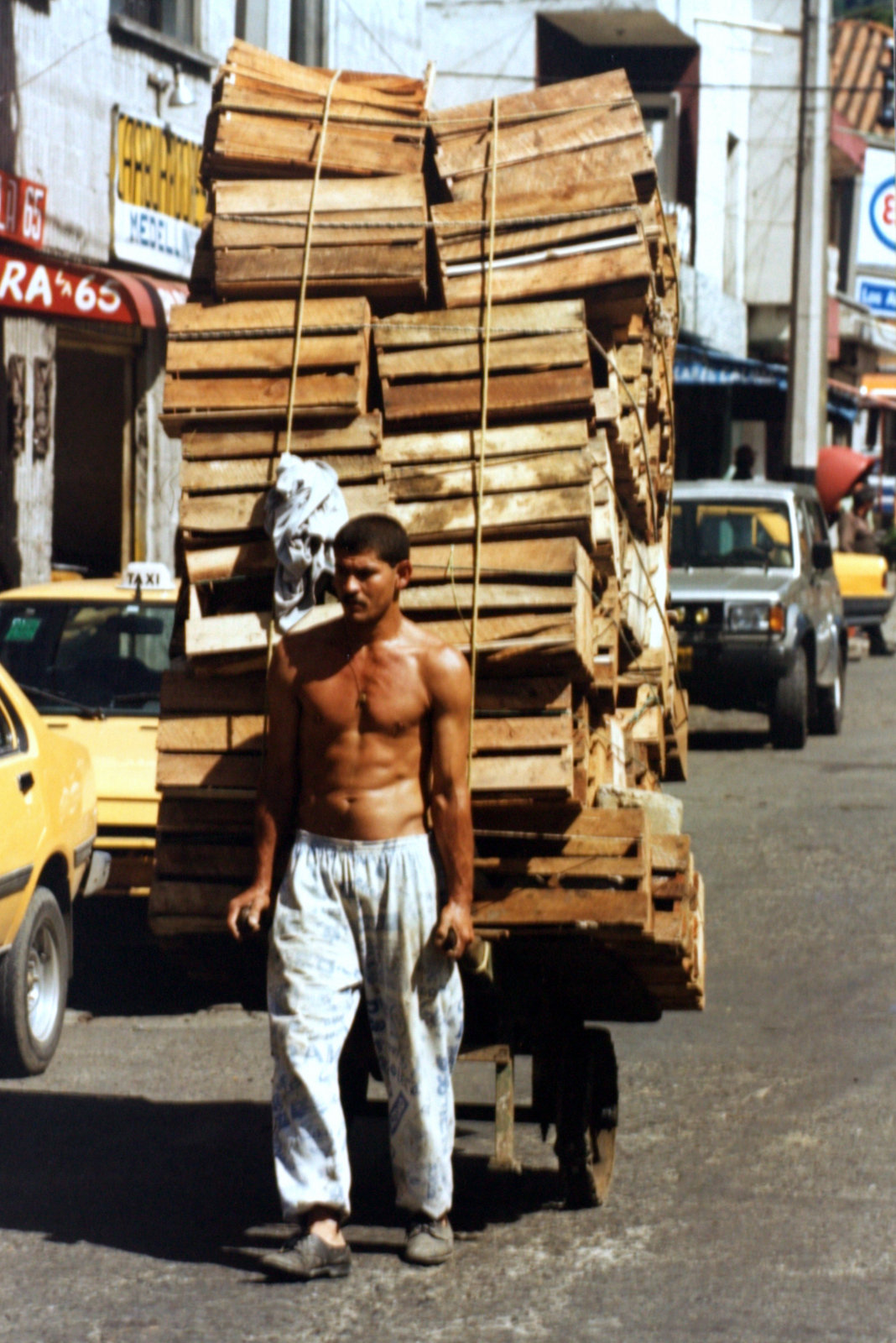

Mr. Preciado lives in New Conquistadors, a jumbled patchwork of tin-roofed homes, many of them perched on precarious slopes. The average monthly household income in his barrio is about $232. Most residents are laborers or street vendors. Some are known as los desplazados – the displaced – people who fled guerrilla or drug violence in the countryside.

Narrow concrete paths snake through their neighborhood. The walls of some homes are emblazoned with the letters “CAP.” That’s short for Armed Command of the People, an illegal vigilante group formed to shield the barrio from drug traffickers and other criminals.

Narrow concrete paths snake through their neighborhood. The walls of some homes are emblazoned with the letters “CAP.” That’s short for Armed Command of the People, an illegal vigilante group formed to shield the barrio from drug traffickers and other criminals.

Many residents are sympathetic to the CAP. Members of the group are harsh critics of the government; they burned several buses recently to prevent citizens from going downtown to vote in local elections.

The U.S. State Department recommends that travelers avoid Medellin because of the danger of violence and kidnappings. A Fielding’s travel guide, The World’s Most Dangerous Places , describes Medellin and the surrounding countryside as “a very nasty area and the most dangerous place in Colombia.”

City of Eternal Spring

Despite the region’s reputation, many visitors find that Medellin is one of Colombia’s more hospitable cities. Most agree it’s beautiful, too. Its mild climate has earned it the nickname City of the Eternal Spring.

These days, Medellin residents are especially proud because one of their own – Claudia Elena Vasquez, a chemical engineering student – was just selected Miss Colombia.

Carlos Mario Baena, 25, who promotes civic and sports activities in Medellin’s Miramar neighborhood, agrees that the city is seeing better days.

“There aren’t as many killings now. There’s more dialogue,” he said.

While drug-related violence has diminished, some analysts say guerrilla activity is picking up.

Left-wing rebels are active throughout Antioquia department, akin to a state, with Medellin as its capital and spanning 25,600 square miles in northwestern Colombia.

Left-wing rebels are active throughout Antioquia department, akin to a state, with Medellin as its capital and spanning 25,600 square miles in northwestern Colombia.

In mid-September, 500 guerrillas blocked an Antioquia highway leading to the Atlantic Coast. Government planes attacked from the air; troops fought with the rebels for days and managed to retake the area by the month’s end.

Antioquia Gov. Alvaro Uribe, whose father was killed by rebels in 1983, applauded the effort. Violence isn’t the answer, he tells anyone who will listen.

A former student of conflict resolution at Harvard University, he carries around cards that give people tips on settling their differences peacefully.

“We’re trying hard to move ahead, to progress,” he said. “For the dignity of our people, for the future of our youth, we feel we have a duty to end violence and drug trafficking.”

Mr. Uribe, 44, a former aspiring bullfighter born on America’s Independence Day in 1952, sat in the back seat of a

four-wheel-drive truck that wound its way from an airport in the town of Rio Negro to Medellin. The truck sped past immaculate hilltop estates, some owned by drug lords and their families. A police official in the front seat gave the governor his daily briefing.

Agents, he said, had just destroyed 326 acres of coca fields, bringing the police a step closer to destroying all 1,730 acres of coca and poppy crops grown in Antioquia.

Several political leaders had argued against destroying the crops, citing environmental concerns. But the governor overruled them.

“We want to free Antioquia of drug plantations,” said Mr. Uribe, whose anti-crime stance has brought him continuing death threats.

His push to clean up Antioquia is part of a broader effort to transform the region.

New skills

In Medellin, the mayor’s office has opened two dozen music schools to help former hit men, ex-gang members and others develop new skills.

“Adolescents who learn to play an instrument will never pick up a gun,” Mr. Naranjo said in a recent speech.

City officials point to other signs of progress: a tripling in the number of paved roads; a new local TV station; free health care for an additional half million people; and government-subsidized Internet connections for 1,800 university students.

And coming soon in selected poor neighborhoods: three “houses of justice,” where social workers, family counselors and others will help residents resolve conflicts peacefully.

Juan Guillermo Sepulveda, a peace adviser to Medellin’s mayor, said the houses of justice are one of many creative projects making the city less violent.

“People don’t believe in justice. Most crimes – 97 percent – go unpunished. We’re trying to change that,” he said, adding, “Medellin is like the Phoenix,” the mythical bird that burned in ancient times and was reborn from its own ashes.

During the grim Escobar years, the annual number of murders peaked at more than 7,000, giving Medellin a homicide rate four times as high as New York’s. That has since dropped to about 4,500, still a formidable number.

“The problem is that when Escobar was killed by the police, an army of people was left without work. Bodyguards, hit men, front men, `dog washers’ – those are the ones who process the coca paste – they all found themselves without a boss and without a job,” said Gen. Alfredo Salgado, head of the National Police contingent in Medellin.

“These are people who are used to being well-fed, well-dressed, with good cars, women. Then their boss dies. Where are they going to get money? Are they going to put on a pair of tennis shoes and go work a construction project? No. They’ll rob banks, they’ll kill, steal cars, sell drugs. That’s why we still have crime in Medellin.”

Despite such problems, Gen. Salgado and many others remain optimistic.

“I’m from Bogota, not Medellin,” the general said. “But one thing I’ve found is that the people here are very creative. They’re very get-up-and-go.

“They’re a very special breed.”