I wrote this piece for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Aug. 18, 1996.

MEXICO CITY – Corrupt police officials dominate Mexico’s anti-drug forces, giving free rein to the murderous cartels that flood the United States with illicit drugs, current and former Mexican police commanders say.

The urgency of the problem was underscored Friday when Mexican Attorney General Antonio Lozano Gracia announced the mass firing of 737 agents, nearly a fifth of the federal police force. Former officers say corruption has gotten so bad that crooked agents not only escort drug couriers and guard shipments but also spy on those who threaten traffickers’ interests.

“Federal police act as the drug traffickers’ Department of Intelligence and Quality Control,” said Juan Jose Tafoya Gonzalez, a veteran police commander who resigned this month.

Corrupt narco-agents also act as enforcers, executing officers who interfere with their lucrative enterprises, former officers say. They say those who talk too much get a bullet in the mouth. Those who know too much, in the ear. And those who snitch, in the neck.

“Where are the good police? At the cemetery. Or they got out of this business, and they’re at home, doing something else,” said a police commander who asked not to be named. “You don’t worry about the drug traffickers killing you. You worry about your own colleagues. I wonder how I’m still alive.”

In Washington, current and former U.S. officials acknowledge deepening concern about the Mexican drug cartels’ growing power and corrupting influence.

“The real long-term danger is not Colombia. It’s Mexico,” said John Walters, deputy drug czar during the Bush administration. “There’s no greater foreign-based threat to the U.S. than drug trafficking, and Mexico, our closest neighbor, is the main thoroughfare.”

U.S. officials say as much as 80 percent of the foreign-grown marijuana, 70 percent of the South American cocaine and at least 20 percent of the heroin bound for the United States is smuggled through Mexico.

Corruption pervasive

Drug corruption has become so pervasive that some Mexican officials wonder whether they’ll ever stop it. Mexican authorities recently agreed to a new bilateral anti-drug plan that calls for unprecedented cooperation from Mexico, a country historically jealous of its sovereignty.

“Drug cartels, with their almost infinite resources, have taken a toll on our ability to face them successfully,” Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo said in a TV interview last week.

Earlier this month, Mexican agents arrested a former police commander who had accused his bosses of protecting smugglers. Ricardo Cordero, whose abilities have been criticized by his U.S. counterparts, said many Mexican anti-drug officials only pretend to combat the problem.

Earlier this month, Mexican agents arrested a former police commander who had accused his bosses of protecting smugglers. Ricardo Cordero, whose abilities have been criticized by his U.S. counterparts, said many Mexican anti-drug officials only pretend to combat the problem.

“The motto at the attorney general’s office is: `Go ahead, corrupt yourself,’ ” he said in an interview before his arrest. ” ‘It doesn’t hurt our country. All these drugs go to the United States. Let the gringos go crazy with drugs.’ ”

Even before Friday’s mass dismissal, the attorney general had publicly conceded that corruption is widespread. When Mexico City’s Reforma newspaper asked him earlier in the week whether it were true that 70 percent of his federal police agents were corrupt, Mr. Lozano shot back: “If not 70 or 80, then right around there.”

Historic nomination

Mr. Zedillo made Mexican history when he named Mr. Lozano attorney general in November 1994, the first time a Cabinet post had been awarded to a member of the political opposition.

But recent criticism of Mr. Lozano’s performance has been intense. It had reached the point, before Friday’s housecleaning, that a Zedillo administration official acknowledged that the president was considering replacing Mr. Lozano by year’s end.

Mr. Lozano’s supporters resent such talk, especially in light of Friday’s developments. And the attorney general says that cleaning up the federal police will take years, not months.

“It shouldn’t be strange for anyone that change takes time,” he said Friday.

Mr. Cordero, a businessman from San Luis Potosi, was named head of a Tijuana anti-drug unit last summer. He said he resigned last November because he was worried that fellow officers were going to kill him for refusing to aid traffickers.

By May 1996, he said, he became convinced that authorities were going to charge him with a crime, so he began to secretly record his conversations to try to protect himself.

In one recording, an alleged Lozano associate urges Mr. Cordero to help him find a midlevel official willing to pay big money for a promotion.

“We’re missing a very good opportunity, man. We can make a lot of dough,” the man tells Mr. Cordero.

U.S. and Mexican authorities say the selling of police and prosecutor positions has been a standard practice in Mexico for years.

“You buy the job. You don’t compete for it. You make back your money the best way you can,” said a U.S. customs official who follows Mexico’s drug trade.

Mr. Cordero and other former officers contend that such deals are authorized by top attorney general’s officials.

Accusations disputed

Attorney general spokesman Juan Ignacio Zavala refuted it and said commanders now are hired by committee to prevent corrupt individuals from hiring their friends in exchange for payoffs.

He added that Mr. Cordero’s taped conversations are worthless. “They don’t prove absolutely anything,” he said.

U.S. law enforcement authorities say they are not at all surprised by allegations of corruption among Mexico’s federal police.

“The corruption’s there,” one official said. “You could write about it all day.”

U.S. authorities say they have known for years that traffickers routinely pay off Mexican police. Ten years ago, U.S. agents, armed with intelligence reports showing who’s paying off whom, asked corrupt commanders to at least help the Americans arrest those smugglers who weren’t handing out bribes, U.S. officials say.

It’s not that the Americans would ignore those who were paying off the Mexicans. But they knew that to nab those traffickers, they were on their own.

Today, making such informal arrangements with police commanders is difficult. Traffickers have formed big cartels that control entire regions, leaving fewer nonpaying dealers to arrest.

Mr. Cordero alleges that his bosses – including the attorney general’s top official in Baja California, Luis Antonio Ibanez Cornejo – protect the Arellano Felix family, led by brothers Ramon and Benjamin.

Mr. Ibanez, who declined to comment for this story, told Mexico’s La Jornada newspaper that the brothers are no longer a problem. He said the Arellanos may be running around in some other states, but not his.

Mr. Ibanez, who declined to comment for this story, told Mexico’s La Jornada newspaper that the brothers are no longer a problem. He said the Arellanos may be running around in some other states, but not his.

“This has ceased to be their territory,” he declared. “We’ve hit them where it hurts them the most.”

U.S. authorities privately dispute that assessment and say they’ve gotten reports that at least one Arellano brother was spotted recently in Tijuana’s red-light district. Mr. Cordero, who had been assigned to investigate the Arellanos, agreed that the brothers are still around.

Mr. Ibanez “wants them to disappear, but not literally. Journalistically,” Mr. Cordero said.

Mr. Cordero and other former commanders also have questions about Americo Flores Nava. He was named head of Mexico’s judicial police earlier this year despite a former attorney general deputy’s contention that his phone number had been found in address books belonging to lieutenants of now-jailed drug boss Juan Garcia Abrego.

Only last Wednesday, after weeks of furor over the latest corruption allegations, did the attorney general reassign Mr. Flores Nava to another post. The former commander could not be reached for comment.

Not clear-cut

Even so, matters of corruption in Mexico are rarely clear-cut. Allegations of dirty dealings are difficult to prove. A police “code of silence” is almost always in force. And even when officials dare go public, the real story often remains murky.

Take the case of Mr. Cordero, who ran a sign-making business before joining the attorney general’s office.

As head of a bilateral anti-drug base funded in part by the U.S. government, Mr. Cordero seemed sincere, but he didn’t know the first thing about going after drug traffickers, U.S. officials said. “Honest, but clueless,” is how one official described him.

Other officials who worked with him said he was a poor administrator, didn’t keep in touch, wandered outside his territory and pocketed $9,000 in U.S. rent money for the anti-drug base.

As one U.S. official put it, “Nobody’s a knight in shining armor here.”

Mr. Cordero went public in mid-July. Mexican authorities arrested him two weeks later, accusing him of a string of offenses, including bribery, robbery and marijuana smuggling. A judge has since thrown out the most serious of the accusations, ruling that he be tried on charges of accepting a $14,500 “gratuity” and improperly freeing three drug traffickers.

A second police commander, Mr. Tafoya, former coordinator of a U.S.-Mexico anti-drug unit, resigned in protest after Mr. Cordero’s arrest. He said he was quitting after 14 years of “useless effort in a hostile and highly corrupt environment.”

Mr. Tafoya complained that his superiors recently slapped him with unspecified administrative violations, then told him he could fix “the little matter” by paying 25,000 pesos – about $3,400. He said he refused and was suspended for 30 days. He said he expects further reprisals – perhaps even being jailed – for speaking out.

“They’re probably going to accuse me of wetting the bed when I was 7 years old,” he said.

The police commander who asked not to be named said he worries about greater threats.

“They’re not necessarily going to kill you right away,” he whispered over coffee at a Mexico City restaurant. “They might wait three or four years. They’re patient. They don’t mind eating their soup cold.”

Mr. Zavala, the attorney general’s spokesman, dismissed the allegations of Mr. Tafoya and other disgruntled officials.

“Why do these people who before were attacked for corruption now have all the credibility?” he asked.

Successes touted

He pointed to the successes: Attorney general’s agents seized 10 tons of cocaine and 402 tons of marijuana during the first half of 1996. They’ve stepped up efforts to destroy illicit crops. And they’ve cracked down on corrupt agents.

More than 1,200 officers have been fired since Mr. Lozano took office, including those involved in Friday’s dismissals.

In one well-publicized case, federal police in Baja California were dismissed and charged after investigators discovered that they had helped unload, then destroy and bury a commercial-size plane that landed with at least 10 tons of Colombian cocaine in November 1995.

In another, more than 30 federal agents were caught guarding an alleged big-time trafficker named Hector “El Guero” Palma. The agents were arrested in June 1995 after Mr. Palma’s plane crashed.

Such incidents convince Mr. Lozano’s allies that he’s a crusader.

“He’s put a lot of narcos in jail,” said Jorge Padillo, a federal deputy. “He fears for his life. He practices target shooting every day. He says, `I realize they’re going to kill me. I’m not going to go out alone.’ ”

Mr. Lozano has plenty of U.S. supporters, as well.

The attorney general and other top-level Mexican officials “are patriotic, brilliant, well-educated and honest people working for the future of Mexico,” White House drug czar Barry McCaffrey said last week.

The attorney general and other top-level Mexican officials “are patriotic, brilliant, well-educated and honest people working for the future of Mexico,” White House drug czar Barry McCaffrey said last week.

“We have a very good, close working relationship with Lozano right now,” said another U.S. official who supports the attorney general. “Most of us in the government think the guy’s clean. We have gotten results from Mexico that we haven’t seen in years.”

Still another U.S. official compared Mr. Lozano to a doctor arriving on the scene of a disaster, tending to the most seriously injured patients first. He’s trying to push through legal reforms and organized crime laws that will make it easier to prosecute drug traffickers, she said. She expects that later he will attack corruption more aggressively.

“We believe Lozano and Zedillo to be trying,” she said. “It would be idiotic to torch the relationship and publicly humiliate them when they’re trying.”

And although Mexican authorities have taken only “baby steps” toward wiping out corruption, she said, the United States can apply only so much pressure.

“Real pressure has to come from within Mexico,” she said. “We want a stable, prospering democracy as our neighbor, but that’s going to take awhile.”

Some blame system

Some say Mexico’s semi-authoritarian political system is what is holding back Mr. Lozano.

As a leader of the conservative National Action Party, or PAN, he is the only member of the political opposition in the Zedillo Cabinet. He’s surrounded by members of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which has run the country since 1929.

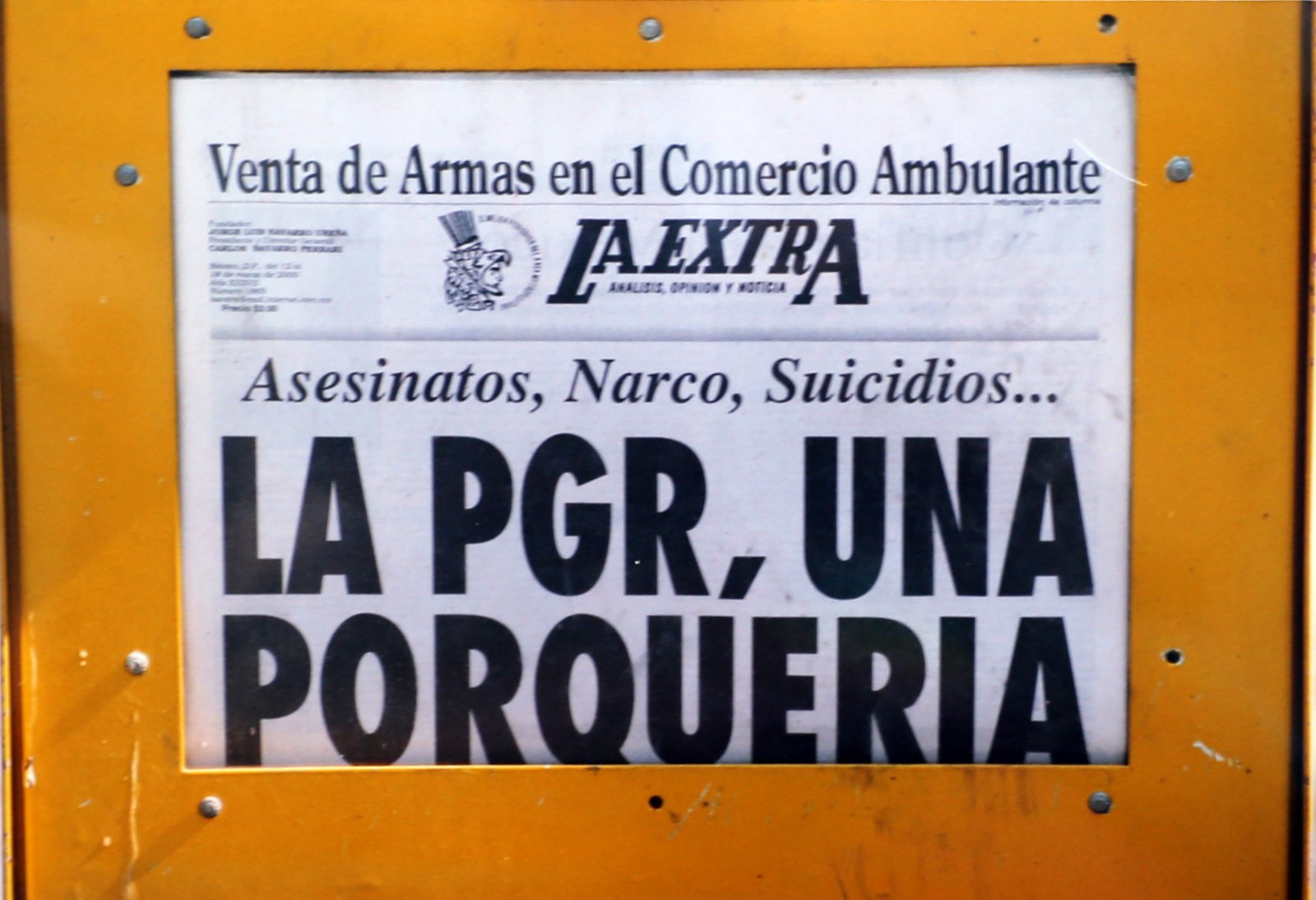

Lozano supporters say the PRI would like nothing better than to discredit the attorney general before Mexico’s crucial midterm congressional elections next year. An indication of a budding smear campaign, they say, is the slick anti-Lozano posters that mysteriously appeared two weeks ago in Mexico City. Hundreds of them – of unknown origin – are plastered all over the campus of the national university.

The PRI scoffs at the accusations and says the PAN and Mr. Lozano are to blame for the corruption and turmoil. The PRI’s latest complaint is Mr. Lozano’s failure to get to the bottom of the March 1994 assassination of Luis Donaldo Colosio, the PRI’s presidential candidate. After fumbling with dozens of theories, attorney general’s officials are now turning toward drug traffickers as possible suspects.

Despite the setback, Mr. Lozano vows to fight on.

“There can be no surrender,” he told Reforma last week. “None of this will stop us.”