I wrote this story for the Dallas Morning News. It was published on Jan. 21, 1994.

OCOSINGO, Mexico – The recruiters started coming around the village a few years ago. Join the rebels, they whispered. Learn to fight back. Learn to kill.

With no money, no land and no prospects, Laura said goodbye to her family and disappeared into the forest for three years. When she picked up her assault rifle and fired on government soldiers for the first time this month, she said, all those years of oppression against Indians seemed to surge inside her. “I felt like killing,” she said. “I felt angry. I felt like letting them have it so they’d be humiliated, like we’ve been humiliated for such a long time.”

Laura, a 21-year-old Tzeltal Indian, is a second lieutenant in the Zapatista National Liberation Army, the rebel group that declared war on the Mexican government New Year’s Day. More than 100 people, mostly rebels, have been killed in the fighting so far, government officials say. Church officials and others say the toll is much higher.

Laura spoke to reporters this week on a remote hillside about 20 miles southeast of Ocosingo, where dozens of rebels were killed in the uprising’s fiercest battle. She wore a ski mask and would give only a first name. She was traveling with about 80 other rebels and a dozen young children, mostly sons and daughters of the fighters.

The rebels’ commander, who identified himself as Major Mario, said they are honoring the government’s Jan. 12 call for a cease-fire and are willing to negotiate with the Mexican

government’s peace envoy, former Mexico City Mayor Manuel Camacho Solis. But he said they won’t lay down their weapons until their demands are met.

They want the government to address nine basic needs: land, work, food, housing, education, liberty, democracy, peace and justice.

Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari has offered amnesty for rebels who surrender. The rebels say they won’t give up so easily.

“I don’t trust the president,” Major Mario said. “During times of peace, he promised many things and we have nothing. We are going to keep fighting the war until we have everything we need. What we want is justice.”

The government has called the rebels misguided peasants and “criminal transgressors” who are led by foreign agitators.

The government has called the rebels misguided peasants and “criminal transgressors” who are led by foreign agitators.

The Zapatista rebels said they’ve quietly been building an army for more than 10 years without the help of foreigners. They said they sell farm animals to raise money and have spent years buying used weapons.

The Zapatista National Liberation Army inhabits the misty forests and jungles of Chiapas, the Mexican state bordering Guatemala. Indians in Chiapas have been struggling for land rights since the Spanish conquest. Scholars say there have been more than 100 rebellions in the area over four centuries. Rebels say living conditions only seem to get worse.

Hungry colonists from the states of Oaxaca, Michoacan and Guerrero have been streaming into Chiapas looking for land. Wealthy cattlemen have expanded their operations, gobbling up chunks of the Lacandona jungle. Peasants from Guatemala have been encroaching from the south. The poor are caught in the squeeze.

“We don’t have anything. There’s land, but only the rich people have it,” said Etigar, a 20-year-old insurgent.

“The poor are left out,” said another rebel, a Chol Indian named Amalia, 20. “My parents work for a landowner, clearing away brush with a machete. They work from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. They don’t make enough to live. My little brothers and sisters don’t have any clothes, any shoes. They go around naked.”

“Hunger brought us together,” said Major Mario. “We declared this war because we can’t stand the misery anymore. We want jobs. We want education. We want real democracy.”

Government officials, Mario said, don’t seem to care that every year hundreds of Chiapas peasants die of measles, cholera and other diseases.

“You go for medicine and they tell you, `Do you have a credential? Do you have the forms signed? Do you have the proper stamp on the forms?’ By the time you get that signature and stamp, more people die,” he said. “I’d rather die for a cause and not of cholera or measles.”

Chiapas, covering 28,464 square miles of jungle and rugged mountain terrain, is Mexico’s poorest state.

Almost half of Chiapas’ 3.5 million residents have no running water. A third have no electricity. Half the homes have dirt floors. Two-thirds are one-room shelters occupied by nine or more residents. And that’s according to government statistics that some criticize as painting a rosy picture.

The rebels say there’s no reason that they should be so poor. Chiapas is Mexico’s leading producer of coffee and bananas. Its hydroelectric plants produce nearly a quarter of Mexico’s electricity. Yet, the rebels say, the riches never find their way into the countryside where most of the people live.

Social tensions run high. A government commission looking into the uprising concluded this week that, as the rebels have asserted, long-standing discrimination against Indians was a key factor in the rebellion.

The rebels say the government treats Indian peasants like “dogs” and “animals,” denying them the chance to progress and educate themselves.

“They say we are dumb, but how can a child concentrate with a belly full of pain and parasites?” Mario asked.

The rebels say they are led by a group known as the Clandestine Revolutionary Indian Committee. They haven’t named any of the members. Their most visible leader calls himself Sub-commander Marcos. In the three weeks since the fighting began, he’s become somewhat of a cult figure in Mexico.

During the first days of the revolt, he calmly stood in the plaza in the colonial town of San Cristobal de las Casas and explained to townspeople what the rebel movement was all about.

With piercing green eyes, light skin and a prominent nose, Marcos claimed to know a smattering of Indian languages and said he was especially well versed in profanities so as to better defend the rebel cause.

Marcos has issued a flurry of communiques, some signed with “health and a hug.”

In one dated Jan. 13, he asked President Clinton to stop the Mexican army from attacking rebels with Bell Ranger helicopters that the United States sold to Mexico for the purpose of combating drug traffickers.

“Don’t stain your hands with our blood by making yourself an accomplice of the Mexican government,” he wrote. “We don’t have anything to do with drug trafficking or national or international terrorism.”

After State Department protests, the Mexican government withdrew the helicopters from battle zones.

The rebels said they began their offensive Jan. 1 as a protest of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which took effect that day. They said the pact – eliminating most trade barriers among the United States, Mexico and Canada – will only make things worse for Mexican peasants.

Marcos said the rebels are tired of rhetoric and government promises. He said Mexican officials have had many chances to help the Indians but instead have continued to look at them as “anthropological objects,” curiosities that are “part of Jurassic Park.”

The Zapatista forces take their name from Emiliano Zapata, a peasant leader during the Mexican Revolution early this century. They say they have more than 10,000 soldiers. Military analysts say 1,800 is a more likely number.

When the uprising began, the rebels had little trouble seizing San Cristobal and three other towns. The Mexican army sent in 16,500 troops, and the Zapatistas retreated to the countryside.

The rebel offensive was “an incredibly well-coordinated military operation,” said a U.S. government source sent in to assess the uprising.

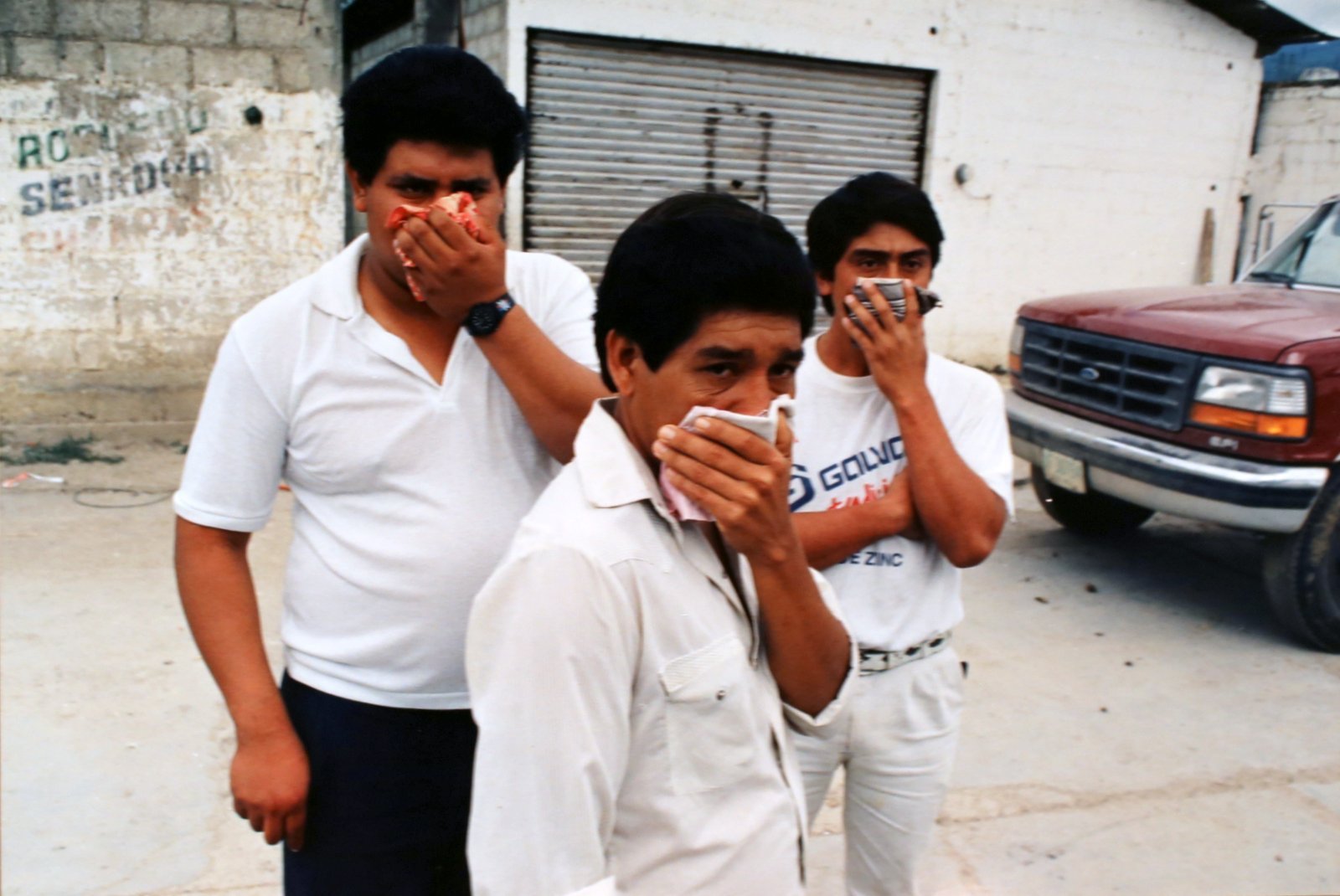

The most serious trouble came when the Zapatistas withdrew, the official said. A contingent of rebels was pinned down by the army near a military base outside San Cristobal. Rebels in Ocosingo stayed behind to try to help, and several dozen were overwhelmed by government soldiers before they could escape.

Military analysts say the rebels have an extensive radio network and have used a code for communications. “A bag of green cement” was the phrase for a Mexican soldier. “A box of fruit” described an armed transport vehicle.

From what these analysts have been able to determine, the rebels fall into three categories:

* Fewer than 100 well-trained combat professionals armed with automatic assault rifles. Some have been seen carrying cellular phones.

* Fewer than 300 midlevel soldiers, most armed with shotguns or .22-caliber rifles. Most of them wear leather boots, brown shirts and green or blue pants. A few wear old helmets, but most have only cloth caps.

* About 1,500 poorly equipped peasants. Some carry only wooden guns with machetes or knives taped to the barrel. Most wear rubber boots that aren’t fit for combat. Many are teen-agers.

Given the rebels’ lack of equipment, one Mexican army officer described the rebel offensive as “suicide.” He said he considered the uprising to be a mere training exercise for the military.

But the Zapatistas have proved a major embarrassment for the Mexican army, and Wednesday the army issued a statement warning that another rebel offensive was imminent.

There was little sign of the rebels Thursday, however, and no reports of renewed fighting.