I wrote this story for the Orange County Register. It was published on Sept. 10, 1992.

YAAPI, Ecuador – The bush plane bounced along the wet, grassy runway, sending mud into the air. Five-year-old Jonathan Stuck grabbed his little sister’s hand.

“Run after the wind!” he yelled. And they scampered after the plane, chasing bursts of air from the propellers.

The red and white plane took off, buzzed the treetops, then disappeared into the clouds. And once again, the Stuck family was alone in the jungle with a primitive band of former headhunters.

Bob and Janice Stuck of Orange County are among hundreds of missionaries stationed in the remote forests of South America. They and their two children live in Yaapi, home to about 250 Shuar Indians.

“We want to save these people from an eternity in hell,” said Janice Stuck, 30, a native of Fullerton.

But soul-saving is controversial, sometimes dangerous, work. Ecuadorean leftists repeatedly accuse missionaries of being spies. Anthropologists say they destroy Indian traditions. And the Indians themselves sometimes resist spiritual conquest.

The Waorani Indians speared two Catholic missionaries in the northern Ecuadorean jungles five years ago.

Less ferocious tribes have protested the way missionaries treat them.

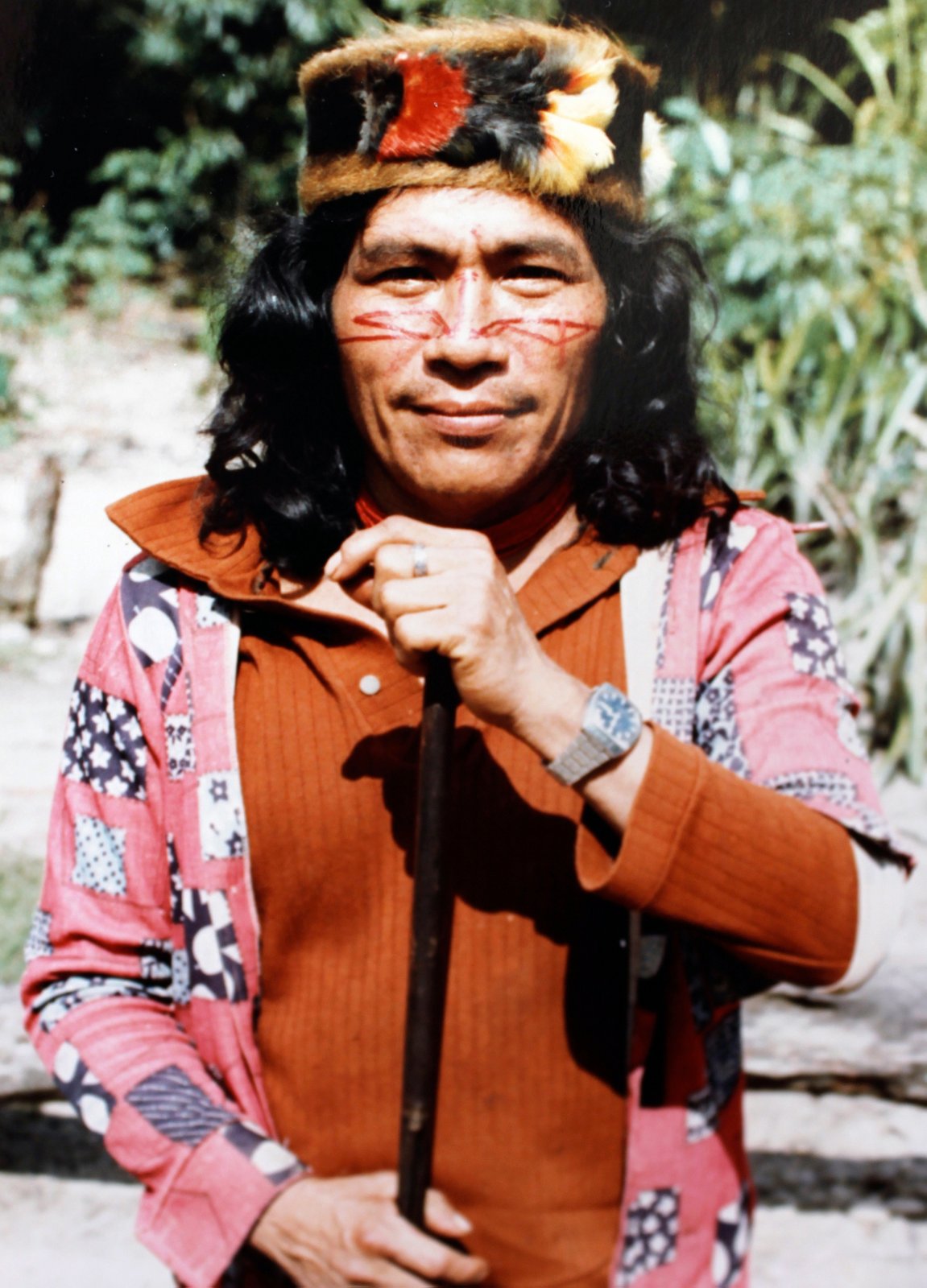

“Some missionaries only want to study us like objects in a museum, like animals in a zoo,” said Guido Pirunchinmi, a leader of the Shuar, a 60,000-member tribe scattered across the southeastern jungles.

The Stucks, sponsored by Calvary Church of Santa Ana, have steered clear of controversy. They said they try to be sensitive to the Indians’ ways. The Indians like that.

“They are good people. Buena gente,” villager Bolivar Shimbiu said.

Bob Stuck (pronounced Stook) is from a family of Orange County missionaries. Born in Santa Ana, he grew up in Yaapi, where his father, John, was a missionary.

John Stuck died in 1972. His son resolved to continue his father’s work.

“If we don’t do it, who will?” he asked.

The Shuar are one of the most tenacious tribes in South America. They fought off the Spaniards during the conquest and were never defeated. Neighboring tribes called them the Jivaros _ savages. As recently as four or five decades ago, they kept gruesome war trophies, the shrunken heads of tribal enemies.

From the capital city of Quito, Yaapi is a bone-jarring six-hour bus ride through the Andes, then a 45-minute hop in a bush plane. The settlement of Yaapi winds along a five-mile stretch of the Yaapi River, a day’s hike from the Peruvian border.owered by a diesel generator.

From the capital city of Quito, Yaapi is a bone-jarring six-hour bus ride through the Andes, then a 45-minute hop in a bush plane. The settlement of Yaapi winds along a five-mile stretch of the Yaapi River, a day’s hike from the Peruvian border.owered by a diesel generator.

The kitchen, with a microwave oven, a stove, a blender and other modern devices, is fully equipped. Janice Stuck often whips up homemade pizza, hamburgers, pancakes, even waffles.

Jonathan and his sister, Lauren, 3, play Nintendo to get through the hot summer days. Their favorite game is Mario Brothers.

“I’m going to get you, bad guy,” Jonathan said one morning, yanking the joystick. “You’re dead meat.”

Living American-style takes some effort.

Bob Stuck usually wakes at 6:15 a.m. to start the generator. Jugs of diesel fuel, canned goods, salt, salad dressing, Coca-Cola and other supplies are flown in every few months.

The Indians consider the Stucks wealthy, although the money they get from the church would put them close to the US poverty level.

Bob Stuck said they don’t try to live like the Indians because that would take time and energy from their mission work.

“The bottom line is the Bible. That’s why we’re here.”

Janice Stuck is just as committed. But she never planned to become a missionary _ until she met Bob. They fell in love, and when he told her that God was calling him to Ecuador, she went along.

In the jungle, they endure bats, tarantulas and other creatures that crawl, fly, skitter and buzz.

One day, a scorpion crawled into Lauren’s rubber boot. She stuck her foot in, felt it and told her dad there was something in her boot.

He banged the boot on the ground, but nothing came out. Lauren put the boot back on. Again she felt something. This time, her dad stuck his hand inside, felt the scorpion and quickly killed it.

Another time, a scorpion squeezed through a crack and crawled into the house. Janice Stuck reached for her weapon, aimed the nozzle and _ ssschooop! _ the creature met its death at the bottom of a vacuum cleaner bag.

“I got creative,” she said.

The Stucks encounter other creatures while visiting in the village _ and sometimes they’re obliged to eat them.

Wasp larvae is one of the Shuar delicacies that Janice has eaten. Her husband once tried grubs.

“They tasted like Crisco in a plastic baggie,” he said.

The Stucks hike into the forest to visit their Shuar neighbors and talk about the Bible two or three times a week. Their work goes beyond the Bible, though. The Indians rely on them for medicine, fuel for their lanterns and advice on how to deal with people from the outside world.

The Stucks hike into the forest to visit their Shuar neighbors and talk about the Bible two or three times a week. Their work goes beyond the Bible, though. The Indians rely on them for medicine, fuel for their lanterns and advice on how to deal with people from the outside world.

The Indians have no electricity or running water. Most of their homes are simple one-room dwellings with dirt floors and walls made of thin bamboolike strips.

Shimbiu, his wife and three children are typical villagers. They grow bananas and other crops and have a few cows.

Shimbiu, in his 30s, has been a faithful convert. But lately, he’s been wondering why God has let so many bad things happen.

In April, a deadly snake bit his 12-year-old brother in the leg. Doctors had to amputate below the knee. An older brother blamed Shimbiu because he had given doctors permission to operate. The two fought, and Shimbiu’s arm was shattered.

The Stucks try to help the Indians through the hardships with prayers and God’s word.

On Sunday mornings, the Stucks go to a tiny wooden church near the edge of the runway. They and the villagers sing hymns in Shuar, the native language.

“It doesn’t mean anything to them to sing songs to the tune of the `Battle Hymn of the Republic,’ ” Janice Stuck said.

Only a few dozen villagers attend the Sunday service. The others stay home, working their land and looking after their cattle.

Measuring the Stucks’ success is difficult. Some Indians follow Christian ways. Others only make a show of it.

“They say, `I’m a Christian,’ but they’ll act like someone who is not,” Bob Stuck said.

These non-believers stick to Shuar traditions. They believe that spirits roam the jungle. Some are good spirits. Other spirits are bad, shooting people with invisible darts that cause death, injury or illness.

Only the tribal shaman can see these spirits. The shaman is known as the “uwishin,” one who sees and knows. He enters the spirit world by sipping a potent drink made from natem, a vine that has an effect similar to that of LSD.

Under the effect of natem, the shaman can see the invisible darts that hurt people. To cure them, he chants a long, monotonous song and then sucks the darts from their bodies.

Cristobal Sanchim, in his 60s, is a Yaapi shaman. On a recent morning, he recalled how he and other warriors used to hack off the heads of their rivals.

They shrunk the heads to the size of a man’s fist by boiling them, removing the skulls and putting them in the sun to dry.

“We had them in house,” Sanchim said in Shuar. “Like

decorations.”

During head-shrinking ceremonies, the Indians drank a beverage called chicha. It remains their preferred drink.

To make it, the women chew the manioc root and spit it into a pot. The saliva helps it ferment, anthropologists say.

“It’s good like beer,” villager Daniel Nayap, 25, said as he sipped the gooey cream-colored beverage from a bowl.

Some missionaries in Shuar villages berate the Indians for drinking chicha, but the Stucks take a soft line.

“Chicha’s their drink, and they’ve been drinking it for years and years,” Janice Stuck said. “I’m not going to tell them it’s wrong.”

The Stucks simply tell the Indians not to get drunk. And they discourage dancing at parties. They said it leads to “sexual lusting.”

Anthropologists criticize missionaries for meddling in Indian affairs. Bob Stuck said missionaries have done a lot of good, including stopping intertribal warfare.

“In a sense, missionaries saved their culture,” he said.

But some Shuar ignore missionary preachings. For many Indians, progress _ not God _ is the big concern.

For centuries, the Indians lived off the land, planting gardens and hunting monkeys, wild pigs and birds. Game isn’t as plentiful now.

“When you’re lucky, you see monkeys, pigs. But there aren’t many,” Nayap said.

So the Indians are trying to raise cattle. They say they’d like to sell their banana and manioc crops to raise money to buy livestock, but Yaapi is so isolated there is almost no one to buy the crops.

Last year, the government of Canada donated $15,446 to the village. The Indians used the money to buy 19 head of cattle, some land and veterinary supplies. They wanted to buy more, but in February, they discovered that three Indian leaders had squandered much of the money.

Last year, the government of Canada donated $15,446 to the village. The Indians used the money to buy 19 head of cattle, some land and veterinary supplies. They wanted to buy more, but in February, they discovered that three Indian leaders had squandered much of the money.

The villagers are still bitter about it.

“We were cheated by people of our own race,” Shimbiu said.

The Stucks face challenges of their own.

“They get the isolation blues sometimes,” said Bob Stuck’s cousin Peter, a Santa Ana missionary who has worked in Ecuador.

They return to the United States for a one-year leave every four years. And friends occasionally visit. Still, they can’t help getting homesick.

Jonathan and Lauren don’t yet speak Spanish or Shuar, so they have few people to talk to. They don’t have school pals because they study at home. Jonathan sometimes gets lonely. And Lauren gets tired of jungle life.

Conversations go like this:

“Dad, I don’t want to walk through the mud,” Lauren says on her way to a neighbor’s house.

“You’re lucky,” he tells her. (Squish, squish.) “A lot of girls don’t get to walk through the mud. Enjoy it.”

Lauren frowns.

“I don’t like it.” (Squish, squish.) “I’m all dirty.”

Life in the jungle isn’t all mud and rainstorms, though.

On hot afternoons, Bob Stuck, his wife and the children often go rafting on the Yaapi River. They swim. They jump from a rock that juts over the rushing water.

Or they watch wild parrots soar over the house, chattering into the wind. Or they go to the little wooden church and sing with their Shuar neighbors.

“It’s not always easy,” Janice Stuck said. “It’s different than Southern California. But we like it. It has its rewards. And we think we’re making a difference.”

SIDEBAR: Proud Shuar have long resisted outside world

The Shuar Indians, known for their fierce resistance to the outside world, have a proud history.

In the mid-1500s, they fought the Spaniards. Two other jungle tribes were wiped out or driven into the desert, but the Shuar were never defeated.

In the 1590s, the governor of Macas in southeastern Ecuador imposed a royal tax. The Indians rebelled, killing hundreds of Spaniards. Then they attacked the governor, stripped him, pried his mouth open and poured molten gold down his throat until he burst. The Spaniards fled north.

From 1690 to 1695, the Spaniards captured 1,360 Shuar. Some Indians hanged themselves to avoid enslavement. Others drove pieces of wood into their throats, choking to death. And some mothers smashed the skulls of their baby boys so they wouldn’t grow up as slaves.

“History tells us that no nation of Amazonia resisted the Conquest more tenaciously. These proud, audacious and indomitable people were attacked and hounded by the whites without relief or pity, but their decimated survivors succeeded in resisting ethnocide. Their indomitable valor is a fine example of what can be achieved by the love of liberty, even among people we presume to call savages,” Alfredo Costale, former director of the National Historical Archives of Ecuador, wrote recently.

In 1964, the Indians founded their own government, the Shuar Federation.

In 1973, they launched an innovative educational campaign, using radio.

Despite these gains, the Indians have gradually surrendered to civilization. They want a piece of the outside world. They want hunting rifles, outboard motors and chain saws.

For a tribe that the Spaniards couldn’t defeat, this has been a sad loss, Ecuadorean anthropologist Juan Bottasso wrote.

“They fell without realizing it into the trap of dependence from which they have never been liberated.”